This report is a summary of a talk given at a meeting of the Local History Group by Dr Sam Lucy on 23 February 2023, with the title Excavations at Trumpington Meadows: Putting the Trumpington Cross in Context, and the subsequent question and answer session. Report by Andrew Roberts, with thanks to Dr Lucy for reviewing a draft and providing illustrations.

Howard Slatter introduced Dr Lucy, referring to her profession as an archaeologist of Roman and Anglo-Saxon Britain, and also as Director of Admissions for Newnham College and for all the Cambridge colleges. Sam Lucy gave an insight into what was found during the Trumpington Meadows excavation, particularly the early Medieval phase of our history. She set this in the context of a broader understanding of the period.

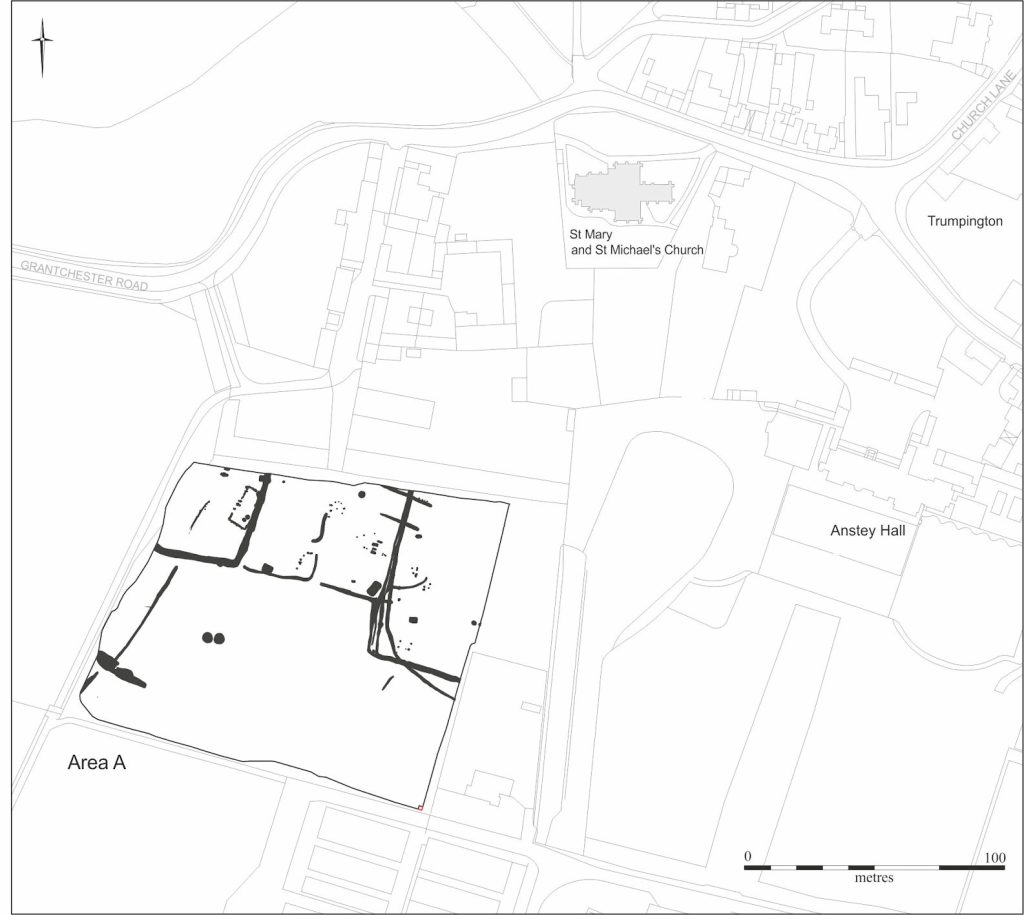

The part of the overall Trumpington Meadows archaeological site where the early Medieval evidence was found is to the south of the Church (Area A). Prior to the start of house construction work, a developer has to pay for an archaeological survey, ranging from desk-based research to a field survey and then a full excavation. This specific area was under crop when the work began, so it was not included in the preliminary surveys, but still called for an open area excavation. The results of the excavation included a later ditch system, a hall-type structure, four sunken feature buildings and a small row of burials. There is no evidence of church activity in Trumpington until the 10th century but the site is close to what became the Medieval village. The excavated area is on the southern edge of what was probably a larger settlement with other buildings and some of the finds give hints that it was a high-status settlement.

The row of four burials was in the middle of the settlement. In the 5th-6th centuries, burials were usually placed some distance from a settlement but in the 7th century there was a change to burials within settlements.

This open area excavation was carried out by the Cambridge Archaeological Unit, with the burials found in 2011. The team used metal detectors, as standard practice. They knew from the outset that there was something unusual about one of the graves because of the evidence from metal detecting.

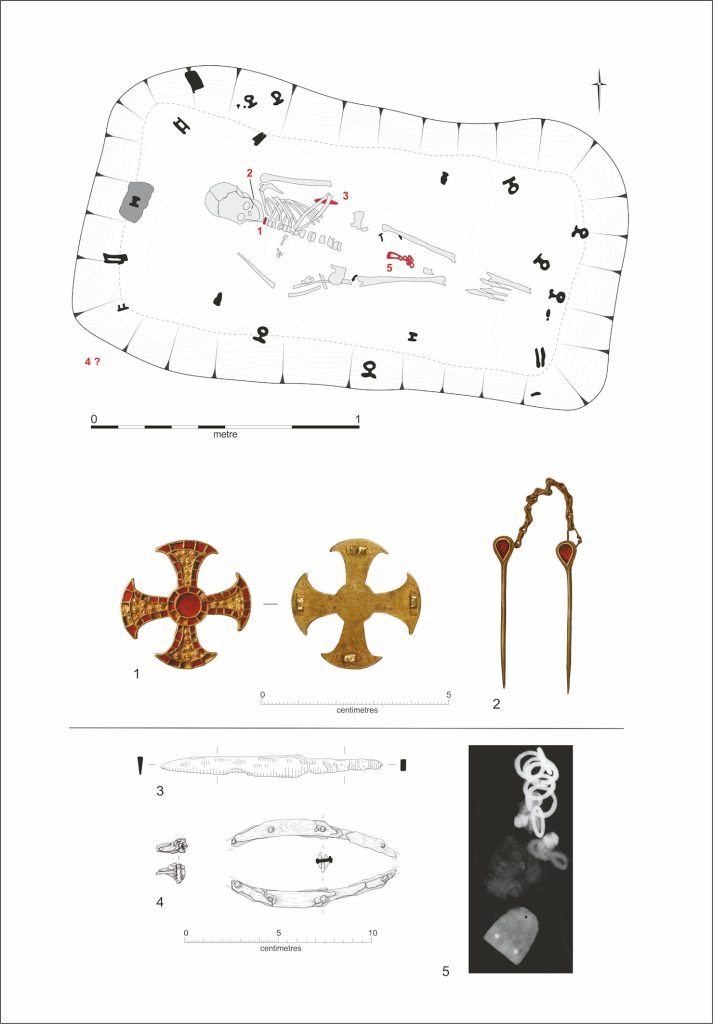

There was a body in each of the four graves. The initial assumption was that the burials were contemporary but this proved to be incorrect and they were probably consecutive over 60 years. Grave 2 was probably the earliest, an older teenager aged 14-15, with a radio-carbon date in the range 600-650, with the body accompanied by a couple of unusual square buckles. Grave 4 held a body of unknown sex, unfurnished, with no grave goods. Grave 3 was an older sub-adult, late teens, dated to 650s-660s. The body has not been sexed but the grave assemblage was of items associated with women, including a key, pair of shears and rivet.

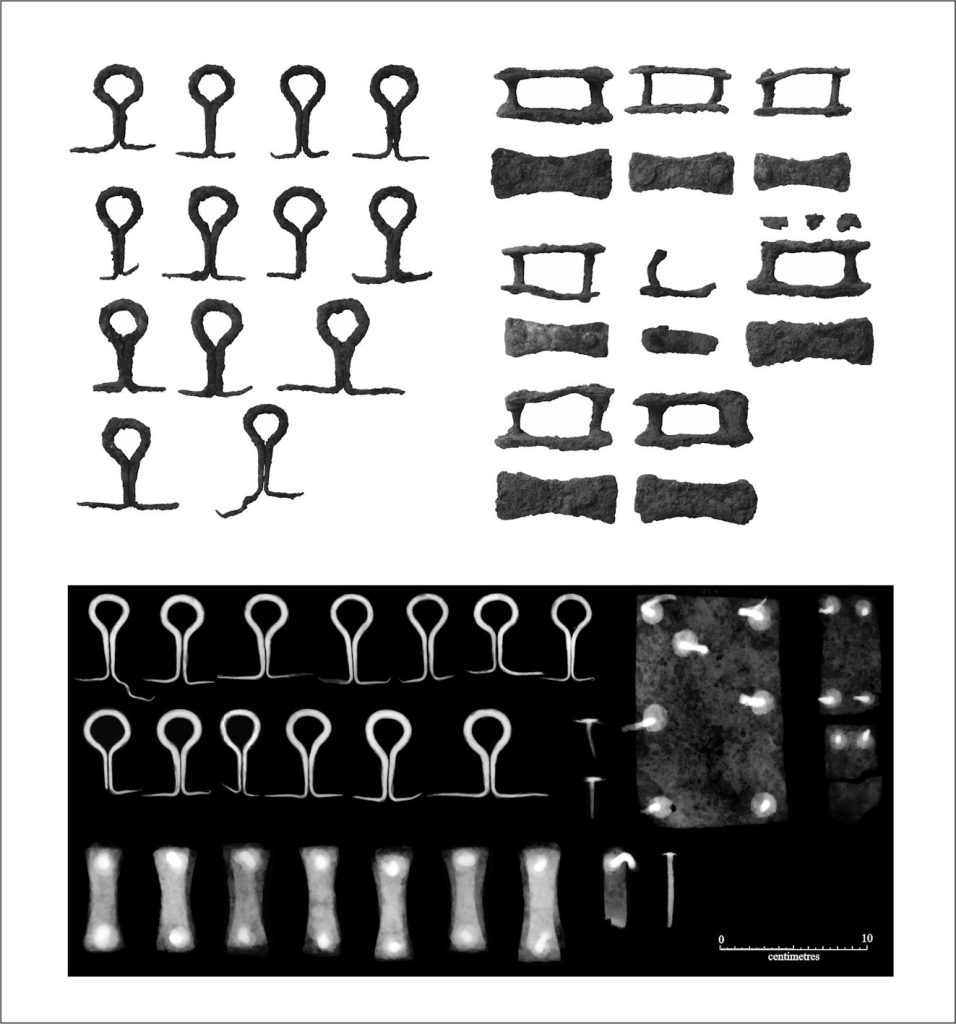

Grave 1 was the biggest and deepest, with probably the last person to be buried in the group, possibly a female aged between 14 and 18 years, probably dated to the 660s-680s. The cross had slipped slightly from its original position during decomposition of the body, though this was still well preserved. The cross is unusual in that it may have been fixed to clothes rather than being a pendant, as there is an attachment on the back of each arm. It is a high-status dress accessory, constructed of gold and garnet of probable Indian or Sri Lanka origin. When the skull was washed after excavation, a pair of linked pins were recovered from inside it, again very fine gold and garnet. These have been interpreted as veil fastenings (veils were common in this period). Sam added that people were buried clothed in this period. The grave included metal fixings, indicating the remains of a wooden box-type bed. The bedhead may have been decorated with a pattern. There was also a bone comb, iron knife and a chatelaine. The chatelaine had a textile impression from a linen underdress, a wool dress and large linen shawl/veil. The evidence reveals a very high-status burial and individual, from the third quarter of the 7th century.

Bed burials in Britain are only found from the mid-late 7th century, with small clusters in East Anglia, Wessex, the North East and the Peak District, usually associated with female burials. Other local examples include Edix Hill (Barrington Quarry).

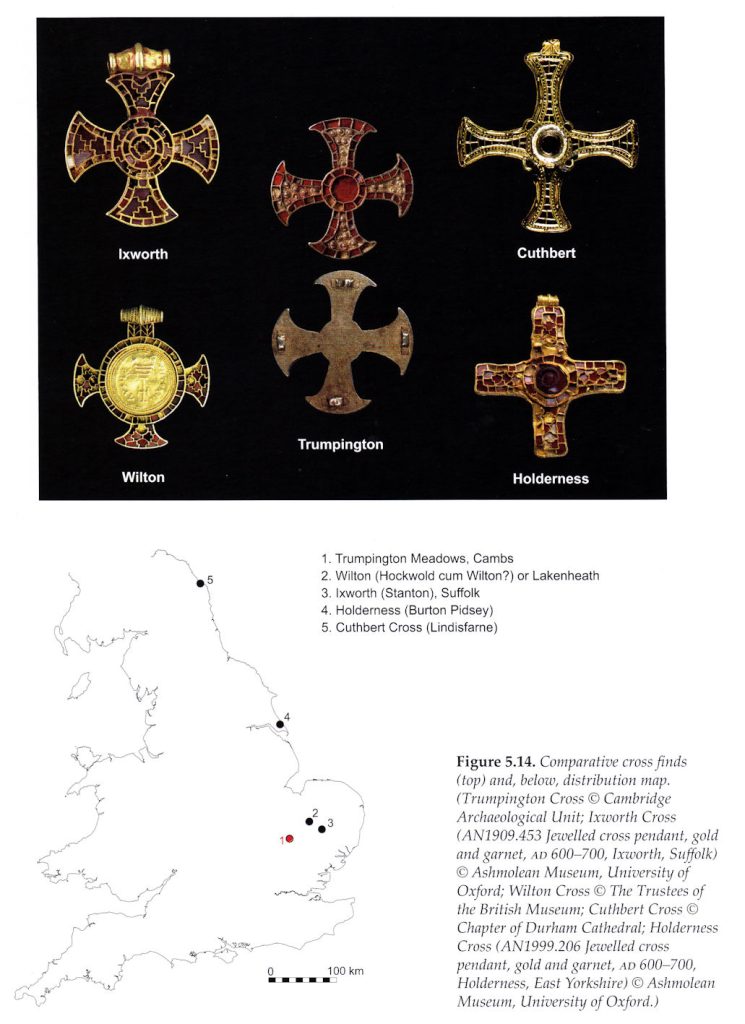

Sam Lucy continued with information about the context for 7th century high status burials. The Trumpington cross is one of five known examples with gold and garnet cloisonné work, sometime called pectoral crosses. It is particularly valuable as an archaeological resource as most of the other finds were poorly recorded by antiquarians, including examples from Ixworth and Witton. The Holderness cross was picked up in a farmyard in the 1960s and then kept in a kitchen drawer (there are 7th century burial sites in the area)! One cross was found in the grave of St Cuthbert. Sam said that the latter example is odd in being found with the burial of a man rather than a woman. It may have been a gift to Cuthbert from a high-status woman. Women had a high degree of influence within the church at this time.

A number of sites have been worked on in recent decades. Bloodmoor Hill, Carlton Colville, Suffolk, was used as a research project, excavated by the Cambridge Archaeological Unit. Radio-carbon dating gave a range of c. 645-680 for burials in the cemetery, which may have been a monastic settlement headed by a female in its later phase. Another example is Westfield Farm, Ely, close to the highest point in Ely. There is documentary evidence for the foundation of a monastery in Ely in 673 and this site may have been the location for the early monastery. The cathedral is some distance away, in the location with the best bedrock. One grave at Westfield Farm was of a high-status female, buried with an assemblage including comb, keys, necklace, blue glass vessels, which had been placed in a wooden padlocked casket; another female grave contained an item which was probably a personal reliquary box. A contemporary cemetery from Cuxton, Kent, including a burial with a similar reliquary box with a scratched image on the handle depicting Calvary.

The overall picture is of burials of high-status women in the middle of the 7th century with objects that indicate an association with Christian religion. These are increasingly being interpreted as women of faith, possibly with influential roles in the church.

Other examples include a recent excavation by Museum of London Archaeology in Harpole, Northamptonshire, where a very degraded burial was excavated and is now being processed in the laboratory. This was another bed burial, revealing an astonishing necklace, including a square cross-type pendant, and a probable processional cross with a central garnet, laid across the body, with attachments that resemble the Trumpington cross. The overall evidence is for a woman who may have had a formal role in the church.

Sam Lucy concluded by saying that each site leads to a revision of ideas. There are few documentary sources for the period and they were often written a century or more later.

Questions

Q: are there example from this period of burials of non-religious high-status people?

A: yes, there are some early merchant sites such as Ipswich, with burials of men, some of which had animal remains and weapons in the burials. Christianisation was happening in parallel and at different times, developing as a top-down religion.

Q: comments on the garnet being from Sri Lanka?

A: we know that there were trade routes, including material from Africa crossing the Mediterranean and another route around the coast of Spain and France. There is a project underway characterising garnets and the bigger ones are usually from India or Sri Lanka.

Q: with respect to Anstey Hall, Christopher Anstey wrote about Roman remains in the grounds of Anstey Hall Farm, close to the current site, and there will be an excavation in the grounds of the hall if planning permission is given for a housing development.

A: it is entirely possible there are Roman remains in the grounds, there is evidence of Roman activity every 300-500 metres across the area. Another local example is Dam Hill (Latham Road/Chaucer Road), were there were antiquarian finds and a possibly significant burial site.

Q: where are the finds now?

A: the finds are held by the Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, with the cross currently on display (February 2023).

Q: politics and archaeological processes

A: an excavation would be preceded by an evaluation and we generally have a sense from the evaluation of the scale of work. With burials, there can only be 1 or 2 staff working on an individual grave and the important burials are typically found on the last day! Sam Lucy said that her daughter was a pupil at Fawcett Primary School at the time of the excavation and she had to be sworn to secrecy when the cross was found, as Sam had brought her out on a site visit just when the cross was found. The excavation is a well-organised process, with more staff brought in as needed. There is often a contingency in the contract. Finds are the property of the landowner but, if there is treasure, this goes to an inquest and the treasure may then be purchased by a museum or donated to a museum. In this case, the cross has been donated by Grosvenor to the Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology.

Q: is it thought that the person came from a wealthy family or had high-status within a religious group?

A: it is assumed the burial would have been the responsibility of the family but certain aristocratic families had a strong allegiance to the church.

Q: are older women found in bed burials?

A: some people would have lived to a considerable age and there are burials of older women. There tends to be a peak of burials of women in their 20s (child-bearing) and older.

Q: the excavated site is close to the present church but not part of the church site, is there any connection between the excavated site and the church?

A: there is no evidence of continuity of settlement but it is entirely possible.

Q: how was the bed constructed?

A: there was a long tradition of fine gold work and metalworking technology, including iron working which would have been well established, as at Rendlesham, Suffolk. There may have been travelling craftsmen for fine working, but most settlements would have had access to blacksmithing.

Q: what happens to excavated bodies?

A: this depends on the context and bodies sometimes have to be reburied. The Cambridge Archaeological Unit aims to deposit bodies in the collection at the university’s Duckworth Laboratory.

Q: is it possible to do DNA analysis?

A: yes, it is possible. We ideally need to know about this at the start of an excavation and prevent cross-contamination. Note that DNA results may not help with ethnicity. Isotopic analysis can indicate that someone grew up elsewhere from where they were buried. Sam added that her sense was that the person was local.

Q: state of the church at the time?

A: the church was not a formal institution. Monastic institutions were founded by people who were aristocratic.

Q: why would there have been a knife among the grave goods?

A: a knife was an everyday item of equipment.

Q: would the person have been regarded as a child or adult? A: people were probably considered to be adult from about the age of 10 in the 7th century.

Dr Sam Lucy was warmly thanked for a fascinating lecture and discussion.