Howard Slatter

January 2025

Introduction

When the Local History Group committee suggested a talk on the “history of natural history” in Trumpington I readily accepted the challenge, as it gave me an opportunity to combine two of my interests. I am interested in our local history but I am also interested in wildlife: originally mainly birds, but more recently insects, particularly butterflies, dragonflies and especially moths. The talk was given to the Group on 24 September 2024 and this page is an edited and extended version.

I will be describing something about what we can discover about the wildlife of Trumpington over the last 5000 years or so, and how it compares with what we have today.

Something of an apology: there are bound to be some of you who know more than I do about some of the things I will be talking about. Secondly an apology to all those who have helped me in researching this. There is not time to mention everything you have told me – I have to be selective. Thirdly I am not much of a photographer. Where possible I have used photographs that were taken in Trumpington, and I have credited those who have kindly given me permission to use their images.

One of my heroes is the Rev. Gilbert White, who was curate of Selborne in Hampshire in the late 18th century. He was curious about everything in his local environment, including the wildlife that he encountered. He recorded what he saw and heard, and corresponded with several people comparing his observations with theirs, thereby forming theories about what was going on at a local level, but also more widely. For instance, in a letter he wrote in 1788 he referred to “some birds like blackbirds with rings of white round their necks” seen by his neighbours in both spring and autumn. He concluded with “If these birds should prove the ouzels of the north of England then here is a migration disclosed within our own Kingdom never before remarked . . .”

So, observe locally and think nationally and beyond.

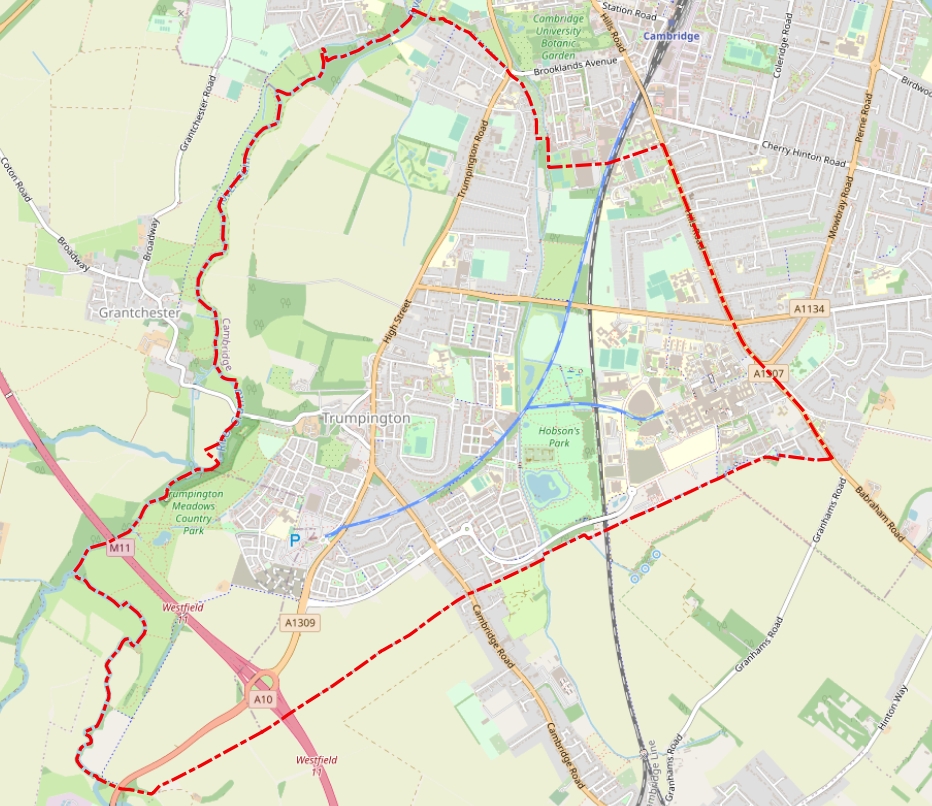

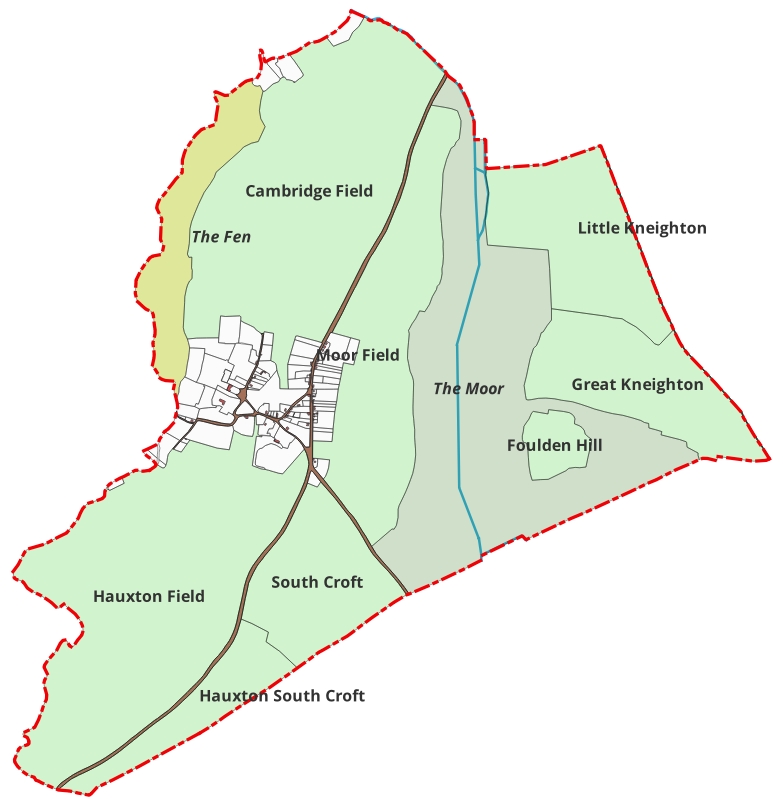

Now let’s look at Trumpington. Here is a map that some of you have seen before: the historic parish of Trumpington. Almost everything I am going to talk about refers to what has happened here over time, but there will be one or two exceptions. The River Cam is on the western boundary, Hills Road on the east; Hobson’s Brook runs south to north through the parish, and there is higher ground either side of the watercourses, but only by 10 metres at most.

There are several natural habitats in Trumpington; the main ones are lower lying wetter ground and the drier “uplands”. This was of course, reflected in the land use in past centuries – you may recall the pre-inclosure pattern of open arable fields on the higher ground, wetter meadows (the Fen) beside the Cam, and damp common land (the Moor) both sides of the brook. There was very little woodland in the parish in 1800, and no standing water other than a few fish ponds.

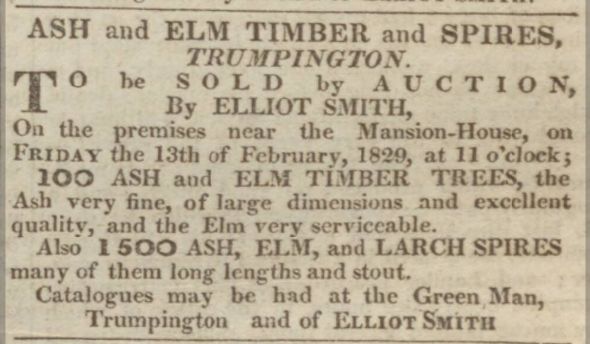

On top of that, of course modern man has made his mark. The Fen and the Moor were both drained in the early 19th century. Substantial tree belts of Oak and Elm were planted along Trumpington Road and the new Long Road, and newspaper advertisements throughout the 19th century refer to timber being sold from there, as well as from the park land near Trumpington Hall and from behind River Farm.

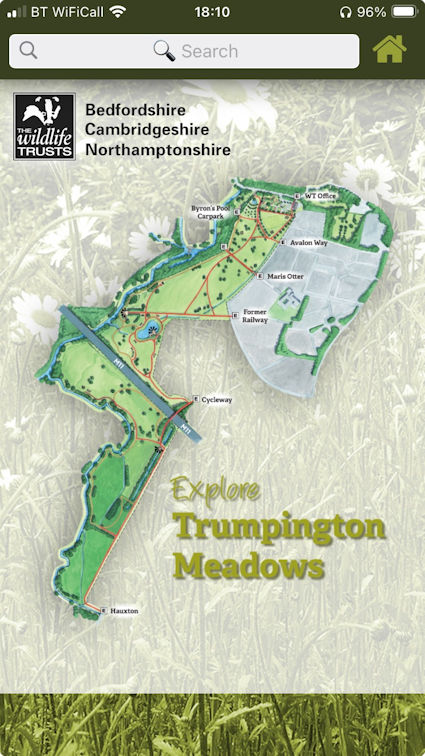

Lots of other changes took place over the 19th and 20th centuries, and then, over the last 15 years or so, on the back of the expansion of housing in what is termed the “Cambridge Southern Fringe”, two major new wildlife habitats have been artificially created: Trumpington Meadows Nature Reserve and Hobson’s Park.

Wild flower meadows have been sown on former farmland, and new ponds have been dug to take the surface water from the developments. Previously the only substantial standing water in the parish was the line of deep coprolite pits on Trumpington Meadows, dug during the First World War. As we will see, these new habitats have had a major influence on what we now call the biodiversity of Trumpington.

Now let’s start looking at our wildlife.

Prehistory

By definition, prehistory has not left us any written records. So we are dependent on what has been found in the fossil record, or archaeological excavations.

As far as I know there are no fossil finds from Trumpington younger than from 100 million years or so ago, and that is not Trumpington as we know it. However, not far from here is Barrington, where a series of bones and skeletons were exposed when digging for coprolites in the 1870s. These have been dated to a much more recent period of only about 125,000 years ago, and include hippos, elephants, lions, hyenas and rhinoceros. So these were probably here too at that time . . .

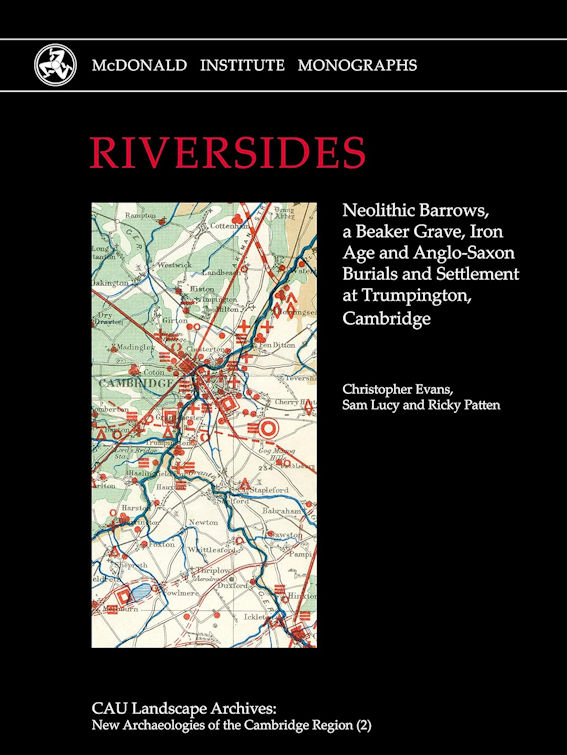

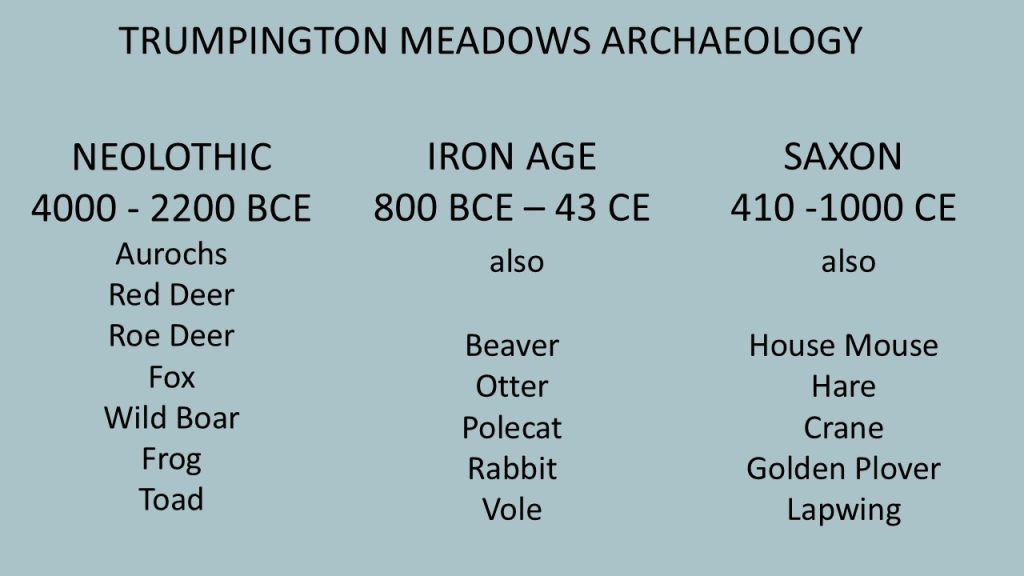

Fast forward to about 5000 years ago. This is where modern day archaeology can tell us something.

All the recent development sites in Trumpington have been investigated by archaeologists before any construction was allowed, and an environmental report is part of the published findings each time. Unfortunately, several of these are yet to be published, but we do have access to a few reports, including that for Trumpington Meadows.

1800 to 1924

There is then a huge gap in our knowledge up until the 19th century. Even in the 1800s, the records are sparse, but there are a few examples.

Cambridge Chronicle of 13th May 1848: “Let us recommend a walk up the Trumpington Road, at any time between seven o’clock and ten at night: the air is then vocal with the notes of the nightingale. Scores of these birds inhabit the trees on either hand, and warble uninterruptedly for the gratification of those who are wise enough to avail themselves of the delights which Nature throws profusely in their way”. Those were the days!

And on a less positive note, skylarks were much more common then in winter than they are today, even on Hobson’s Park and Trumpington Meadows. The Cambridge General Advertiser of 25th Jan 1850 reported, under the heading “Supply of Larks”: “that a poulterer in Cambridge had an extraordinary quantity of these birds brought to him. Above three hundred dozen were caught in three days in the village of Trumpington (that’s over 1000 a day). These birds during frost and snow migrate from the fens to the uplands, and afford employment to many poor labourers when the weather is too inclement for them to pursue their usual out-door avocations.”

The Great Bustard is the subject of a reintroduction programmme on Salisbury Plain, as covered by the BBC Countryfile programme in September 2024. In 1904, a story was published that Dr William Clark, Professor of Anatomy, used to say that once, in the early 19th century, while riding over Trumpington Heath, he came across a strange bird on the ground. He took it up and brought it to Cambridge, when, finding that it was a young Bustard, he rode back to the place where he found it and left it there. However, there is something wrong with this. Great Bustards are birds of open dry country. They ceased breeding in Cambridgeshire on Newmarket and Royston Heaths in the very early 1800s. But they were at one time significant enough in Cambridgeshire to appear as the supporters of the Arms of the County Council. The real problem here is that there is no such place as Trumpington Heath. There is just no heathland anywhere in the parish; if there were such a place it would have appeared in the Inclosure Award of 1809, and it does not. Trumpington Moor, yes, but that was damp low-lying land either side of Hobson’s Brook. So this record has to be classed as at best “apocryphal”, though it has reappeared at intervals, with elaboration, for over 100 years. So don’t believe everything you are told.

These 19th century examples all refer to birds. There are also a few scattered records of plants found here, but time does not allow me to go into those in detail.

So now on to the last hundred years.

1925-2024

There is now enough material to break it into sections.

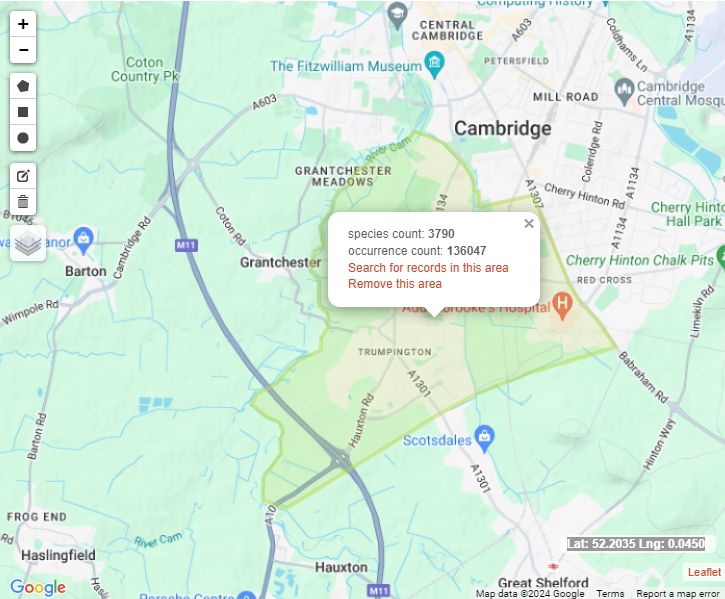

There is an online “National Biodiversity Network (NBN) Atlas”, which holds millions (literally) of records from all across the UK, of thousands of different species. When I started to prepare for this talk, I thought all I had to do, in the absence of other information, was to go to the NBN Atlas and search for records within Trumpington.

However, it wasn’t as easy as that! I found it somewhat cumbersome to use, and even when I found a record for Trumpington the detail was usually very thin. Also, it is clear that some of the datasets badly need updating. So I will not be making many further references to the NBN.

Plants

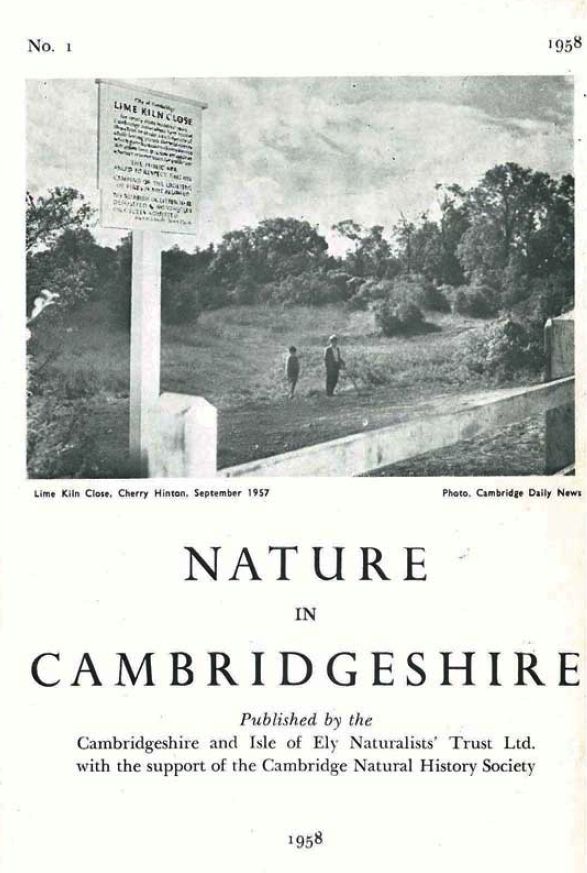

In 1958 a new annual journal made its first appearance: Nature in Cambridgeshire. I have spent many happy hours combing through over 60 years of reports, and found a few that related to Trumpington. Most of them refer to plants and I have to skip over the details. But among them are references to “that plant haven where the St Neots and the Royston lines formerly met near Long Road” and to a 2017 record of Marsh Pennywort at Trumpington lakes off Trumpington Road, which was last seen in the Cambridge area on Trumpington Moor in 1820. This is not to be confused with another species which I will discuss shortly.

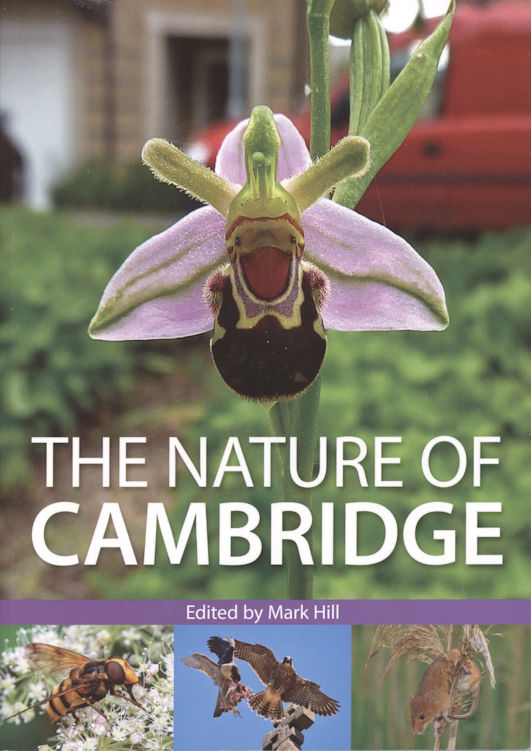

In 2016 the Cambridge Natural History Society embarked on a project to “create a snapshot of the flora and fauna of Cambridge city and its immediate environs in a historic context and to increase public awareness of the diversity of plants, animals and fungi in the city”. The culmination of this project, whose scope included Trumpington, was the publication in 2022 of the book “The Nature of Cambridge”, a wonderful resource.

Botanical records in “The Nature of Cambridge” for Trumpington include two alien invasive species: Hydrocotyle ranunculoides Floating Pennywort related to, but very different in habit to, the Marsh Pennywort – more later; and Oxalis corniculate Creeping Woodsorrel, a well known rapid coloniser of gardens and other bare soil.

There are also two resources on our website with useful information about the wild plants of the parish.

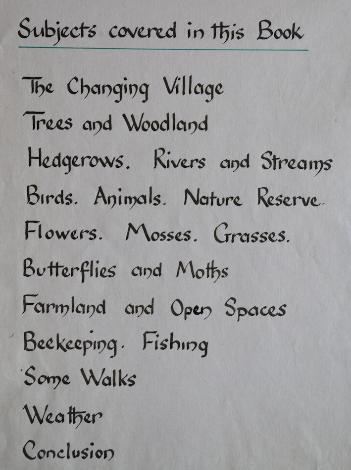

In 1970 the Trumpington Women’s Institute (WI) produced an album entitled “The Countryside 1970 Trumpington” with information, illustrations and photographs about the village and its environment. This is now on our website. It includes a list of wild flowers identified along the disused railway line between Long Road Bridge and Shelford Road Bridge – in flower – 18th June 1970, on the web page.

Then in 1984-85, Pam Stacey, who lives in Bishops Road, did a research project on the flora of the western half of that same section of railway line, concentrating on the part in the cutting west of what we now know as the Clay Farm Community Garden. Pam’s report on the project also appears on our website. It is a particularly useful document: since 2010 the Guided Busway has been built and destroyed much of the site. It would be a fascinating exercise for someone to undertake a comparison between these two reports and what can be found there today.

Some definite changes have happened over the last century. For example, we have been invaded at intervals by over-vigorous aliens. In 1988 Byron’s Pool was described as “flanked by seven-foot high forests of Himalayan Balsam”. That is, thankfully, not the case today, though it is still present. Also at Byron’s Pool and downstream in 2016 there was a bank-to-bank mat of the alien Floating Pennywort. I was part of a work party that punted upstream from Scudamore’s on the upper river in 2017, in order to clear sections of this from the bank. After repeated attacks by many volunteers, led by Trumpington’s Mike Foley, this now seems to have been eradicated. Mike also successfully attacked an infestation on the Shelford Stream which feeds into Hobson’s Brook on the parish boundary.

At intervals I have attempted to identify the flowering plants I meet with in the wild, but have found it hard work using one of the published identification guides or floras.

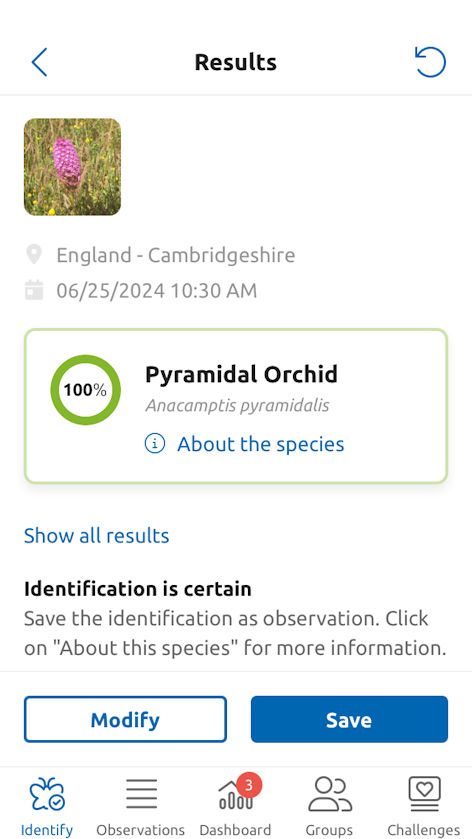

Nowadays technology comes to our aid: I asked my Obsidentify app on my phone to confirm my tentative identification of this orchid on Hobson’s Park, and was glad to see it give me 100% confirmation that it was indeed a Pyramidal Orchid. But such things are not infallible – more on modern technology later. This species and Bee Orchid are now both firmly established on the “new” meadows in both Trumpington Meadows and Hobson’s Park.

For further reading, there are two detailed reports from the Cambridge Natural History Society NatHistCam project published in “Nature in Cambridgeshire”, and they are available online: 2013 on Trumpington Meadows and 2014 Clay Farm. Both concentrate on plants, but mention other species too.

Insects

I have found it hard to find any historical records of insects, except for moths. The NBN website has distribution maps for a wide range of species (as for all plants and animals) but local records are hard to pin down. Therefore, we must make do with a few recent highlights.

Hoverflies. Bill Amos has identified over 100 species of hoverfly on Trumpington Meadows. This shows what a difference a single competent observer can make.

Ivy Bees were first recorded in Dorset in 2001, having arrived from continental Europe. They have been in our county from 2014 onwards according to the Bees Wasps & Ants Recording Society (BWARS). Now commonly seen at this time of the year flying over their burrows in cleared soil such as gardens and allotments, and on Ivy flowers.

Dragonflies. It is hard to ascribe recent changes locally to either national trends or to changes in the local environment. I have recorded 20 different species of dragonflies and damselflies in Trumpington; 15 of these at my garden ponds.

Three species have certainly been spreading northwards in recent years, and this coincides with the availability of new suitable habitats in the form of the balancing ponds on Trumpington Meadows and Hobson’s parks. In particular: Willow Emerald Damselfly (seen in my garden), Lesser Emperor and Small Red-eyed Damselfly. These recent arrivals from Europe are almost certainly a consequence of climate change.

Percy Robinson (1878 – 1943) was the village schoolmaster here from 1908 up to his death. He left many photographs and documents about the village, of which the Local History Group has copies, and these are now on our website. He wrote in the 1920s: “of butterflies the clouded yellow has been taken (by which word he meant, of course, trapped and killed) some years upon clover” (one of my favourite butterflies, seen by me on Hobson’s Park in seven autumns since 2000, and several on Trumpington Meadows in 2020).

You will have heard of Butterfly Conservation’s “Big Butterfly Count”, and how the 2024 results were the worst on record. In general, butterfly numbers are decreasing alarmingly.

But two species have bucked the trend in Trumpington. The Marbled White was seen first by me here in 2017, and since has become one of the commonest butterflies in June over both parks. This reflects a national increase away from its former stronghold in south-west England. The Small Blue has bred on Trumpington Meadows from 2018 onwards, as related by Iain Webb when he spoke to us in February 2024.

Every ten years or so we see an invasion of Painted Lady butterflies. I recall that one afternoon in May 2009 I was digging my allotment on Foster Road and saw dozens of these fast-moving butterflies flying in a north-westerly direction. They spend the winter in North Africa, then migrate northwards, stopping at intervals to produce a new generation, until they reach here, flying back south in the autumn.

Moths

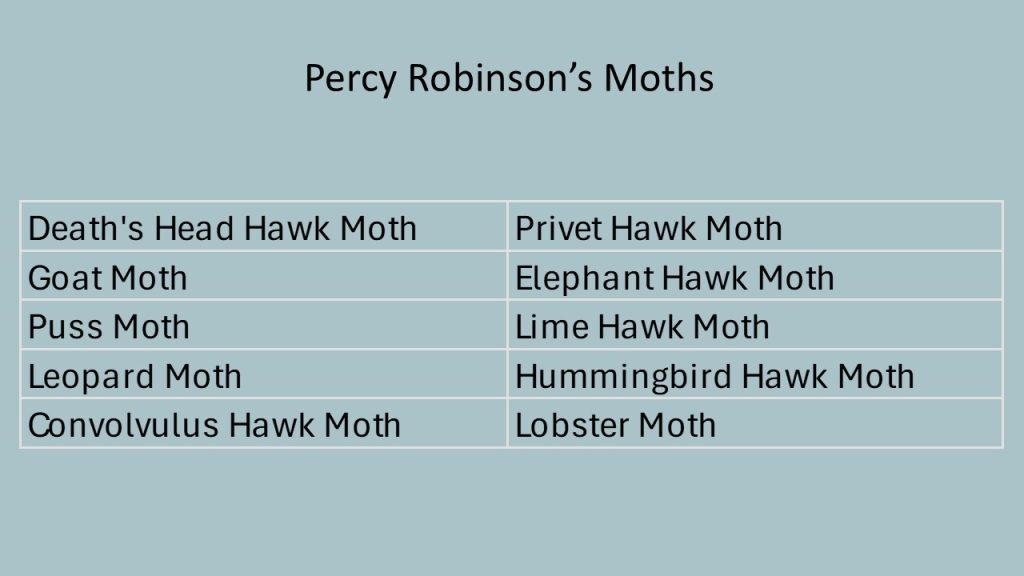

Percy Robinson wrote: “From an entomological point of view Trumpington may vie with Wicken Fen as a collectors’ rendezvous. (I think this was a bit of hyperbole on Robinson’s part!) The death’s head moth was plentiful about 1900 when pupae sold at 2d. each when potatoes were lifted.” Robinson’s list of moths included two I have yet to record here (the first two on his list).

I have now been light-trapping and identifying moths in two of my Trumpington gardens since 1995. Chris Thurgood has been doing so in his garden for the last ten years. There is a weekly moth trap run on Trumpington Meadows, but otherwise we are not aware of anyone else regularly trapping here, though there have been occasional sessions, such as National Moth Night a few times in the Community Orchard, and five annual “bioblitzes” organized by Hobson’s Conduit Trust.

Chris Thurgood and I have seen changes over time in a number of species. A report by Butterfly Conservation in 2021, “The State of Britain’s Larger Moths”, shows population declines in many species, but also a general northward movement for many, almost certainly in response to climate change. In Trumpington, we have seen increases in several species.

Jersey Tiger moth was first recorded in any numbers in the county in 2017. In 2022 Chris had 14 of these one night in his garden.

Black-spotted Chestnut moth: the first Cambridgeshire record was in Chris Thurgood’s Trumpington garden in 2018, and he now regularly has double-figure counts during its flight season, which is from late October to early March. In fact, Byron Square is considered by some knowledgeable “moth-ers” to be the best site in the country for this still uncommon species.

Box-tree moth. First recorded in Kent in 2007, this is what is termed an “adventive species” from south-east Asia, introduced accidentally with imported box plants. After moving from Shelford Road to Baker Lane in 2016, I trapped my first Box Tree Moth the following year. The new developments were planted out with lots of box hedges, and this species thrived, with impressive consequences for those hedges! I recorded my highest catch just two years later, when there were 259 of these at the same time in my light trap. After that the counts gradually went down as they must have been running out of their food plant locally.

As well as Chris’s Black-spotted Chestnuts, his other claim to lepidopteran fame is trapping a first for the UK: an American species known as the Autumn (or Fall) Webworm which he caught in his garden in 2014.

I cannot match that, but did have a county first in my Shelford Road garden in June 2006. This was a scarce migrant species from North Africa, the Blair’s Mocha, which has rarely made its way this far north, but is now breeding on the Isle of Wight.

In September 2024, Chris caught the first Clifden Nonpareil moth for Trumpington – something of a mythical moth. Much commoner than it used to be, but I am still very jealous!

The Toadflax Brocade moth is also spreading northwards, and we now see caterpillars every year on the Purple Toadflax in the front garden.

The Humming-bird Hawk-moth is also seen far more frequently now than in the past. I used to associate these with holidays in France, but they are now in our garden nearly every year.

When comparing present day records with past ones, we have to take into account advances in modern technology. The light traps of today were not around 50 years ago. And one other innovation has revealed the presence of species we just were not seeing before.

There is a thing called a “pheromone trap”. The females of many moth species produce pheromones to attract males. These chemical signals can travel in the air for a considerable distance, and are detected by males who then follow the trail back to the female.

Several of these pheromones can now be made artificially. If a “lure” impregnated with a pheromone is hung up in the right place at the right time it will attract males of the appropriate species.

Chris Thurgood’s garden has several different lures designed to attract day-flying moths known as Clearwings. If you look at older (just 20 years or so old) books they will talk of low populations of most of these species, rarely seen. However, Chris has now had 10 different species to his lures. So, the technology, combined with a competent observer, extends our knowledge about local wildlife.

The Red-tipped Clearwing is one of the species Chris Thurgood has caught.

Day-flying moths also include the Emperor (which also comes to a specific lure, but I have been unsuccessful so far in my first year of trying).

Also, the Six-spot Burnet moth is now common on knapweed and field scabious flowers in June in Trumpington Meadows and Hobson’s Park, as a consequence of the creation of lots of new habitat for them.

Fish

I do not know much about fish, and there may be anglers who can add to the little I can report.

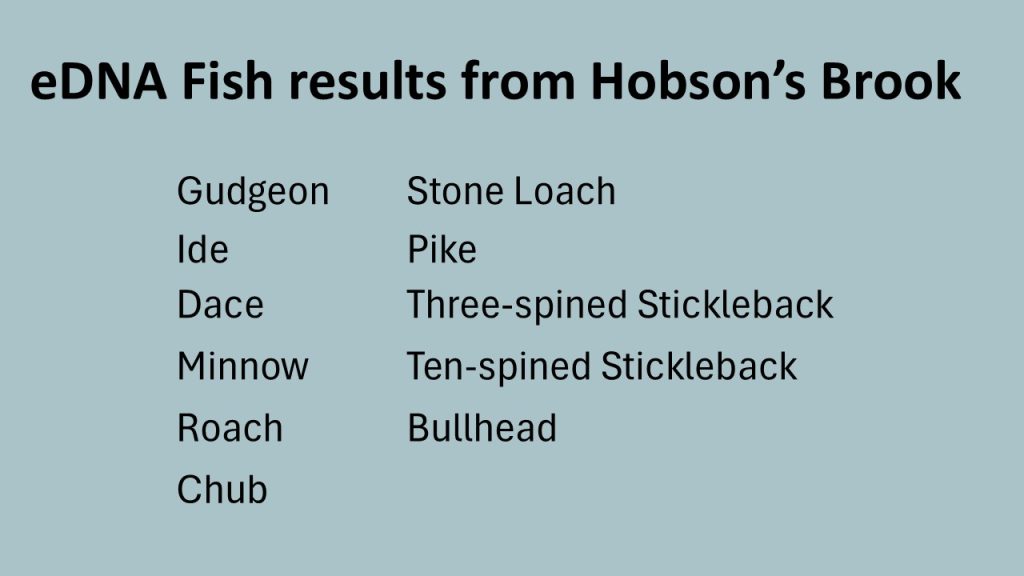

If you stand on one of the footbridges over Hobson’s Brook you can often see minnows and sticklebacks in the water. Another technological innovation has extended our knowledge here. Environmental DNA (eDNA) can be analysed from a small water sample, and provides evidence of which species are present. This was done in 2023 at several points in Hobson’s Brook, and the following fish species were found.

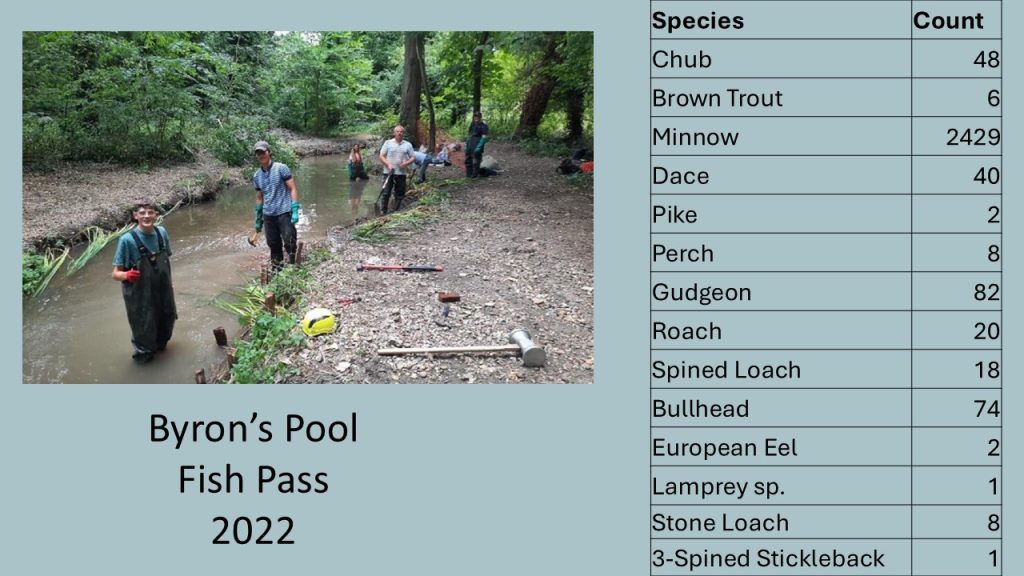

The fish pass at Byron’s Pool was created originally in 2011 to allow fish to travel upstream past the weir on the River Cam. In 2022 some enhancement work was carried out, and prior to dewatering the channel the City Council undertook an electro fish survey and translocation, which involved temporarily stunning the fish with an electric current and moving them out of the channel back into the river itself. They recorded the following 14 species, including a good age range, indicative of local breeding.

Amphibians and Reptiles

Common Frog and Common Toad are still, as their names suggest, both still fairly common though decreasing, in both garden ponds and larger water bodies.

Smooth Newts are often found outside the breeding season away from water (e.g. allotments).

Grass Snakes are quite common, in damp places and in water bodies.

Common Lizard was last recorded by me in July 2003 by the old railway cutting.

Slow-worms are uncommon in Cambridge: the only record on the NBN is from 2011. However, in 2017 we found one in our Shelford Road back garden, and there is clearly a stable population there, with a maximum of 9 seen on one day in 2024, including “babies” from the previous year. The observer effect again?

Mammals

Percy Robinson wrote: “Stoats and weasels play havoc with the game, but they are well looked after by the gamekeepers, as a view of the “gibbet” will show.” To some the sight is repulsive, whilst sportsmen may have a different opinion. It is not often a gibbet such as this can be seen so near a town. It shows the remains of weasels, stoats, hawks, jays and magpies, all enemies of game. In the picture may be seen the “Lord High Executioner” Mr. Armond Cannell, the game keeper on the Pemberton Estate. But this was 100 years ago.

This table shows the various species of mammal recorded on Trumpington Meadows. I think the most interesting is the Harvest Mouse, found there from 2018 onwards.

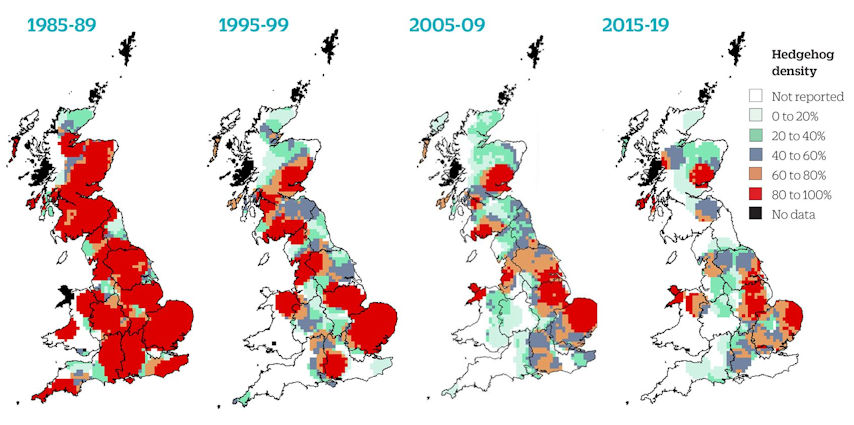

Hedgehogs are far less common now, again in keeping with national trends. The State of Britain’s Hedgehogs (published in 2022) shows the shrinkage of their range.

Hares can still be seen on Trumpington Meadows and Hobson’s Park, as well as on what remains of the farmland in the parish. I have seen up to 5 at a time on Hobson’s Park.

Otter. Percy Robinson wrote in the 1920s: “Otters are far too plentiful from a fisherman’s point of view, but owing to the depth of water the hounds find it difficult to kill.”

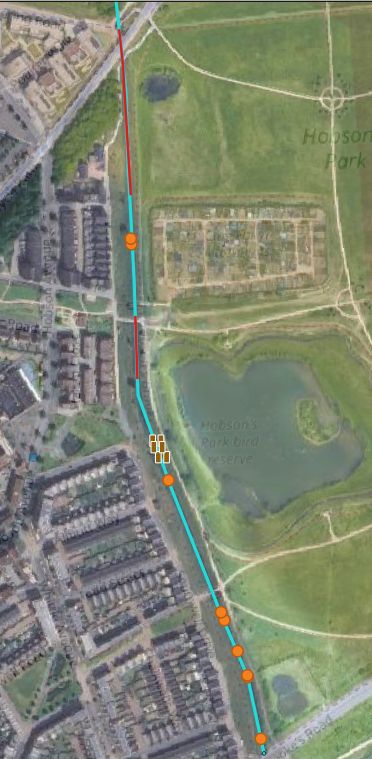

Water Vole. Nature in Cambridgeshire 2004 reported a “99.8% crash” in the population between 1989 and 1997. There had been a long-term decline since the 1900s, but then a huge crash from predation by American Mink. Mink have now decreased and almost disappeared, primarily because of the recovering otter population, but also as a consequence of a human control programme. Water Voles have recovered somewhat since then. A survey by Hobson’s Conduit Trust in 2024 shows many burrows along Hobson’s Brook: the orange dots on these two maps.

Badger. The first NBN record for our part of Cambridge was in 2004. They have since become much more common, with an obvious sett in the Guided Busway cutting, which, I have noticed, after inactivity for a couple of years is now being dug out again (2024).

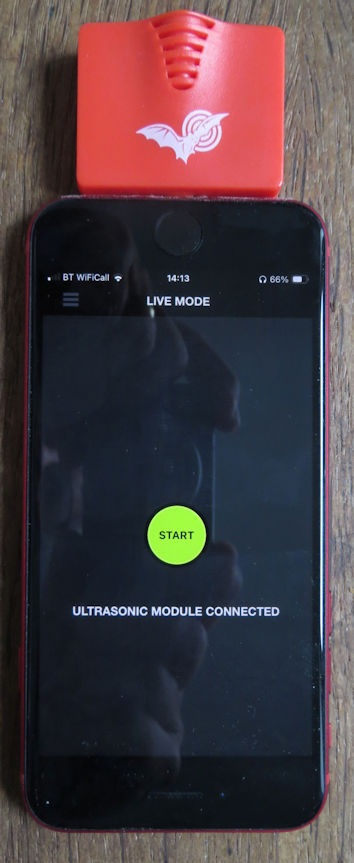

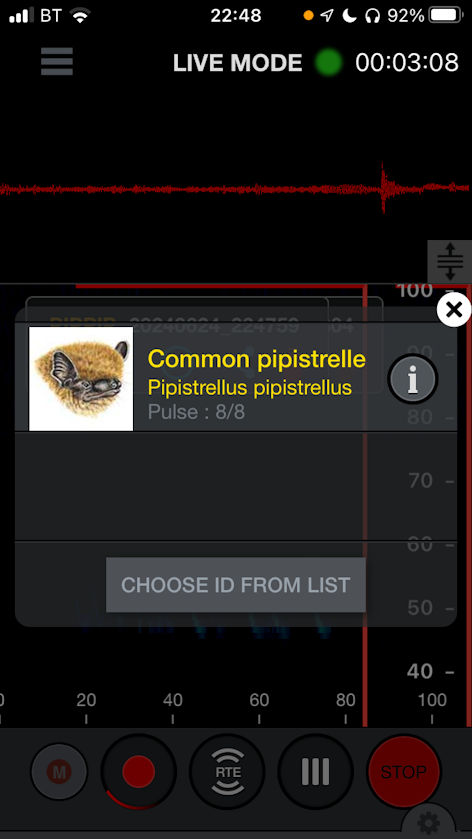

Bats. Nowadays you can get a bat detector to make the high frequency calls of bats audible to the human ear. I have one which plugs into the end of my phone. Point it at a bat on a summer evening and it will tell you what it thinks it is. Like other technologies, it needs treating with a bit of healthy scepticism!

Birds

Our first Trumpington records come from Percy Robinson. He wrote, again in the 1920s: “Some of the prettiest and rarest of British birds are by no means uncommon.” And he then went on to list these species.

Of these, the Firecrest was extremely scarce a hundred years ago, and the Corncrake would still have been breeding here, though long gone now. David Stubbings relates Corncrakes being in grassland behind Shelford Road just after the Second World War.

The WI report from 1970 includes a list of birds seen in and around the gardens of Trumpington during 1969/70.

Some interesting species are mentioned here, highlighted in yellow. The Sparrowhawk was declared “virtually extinct” in Cambridgeshire by 1965, according to the annual Bird Report. And the other three have declined hugely on a national scale, so are now very rarely seen. In the 1980s the Lesser Spotted Woodpecker was the commonest of the three woodpecker species in Trumpington. The other two used to breed here quite commonly, but are now only seen occasionally on autumn migration.

There is still a rookery in Long Road. The one in Grantchester Road, I have on good authority, was regularly “shot up” in springtime, and is no longer there.

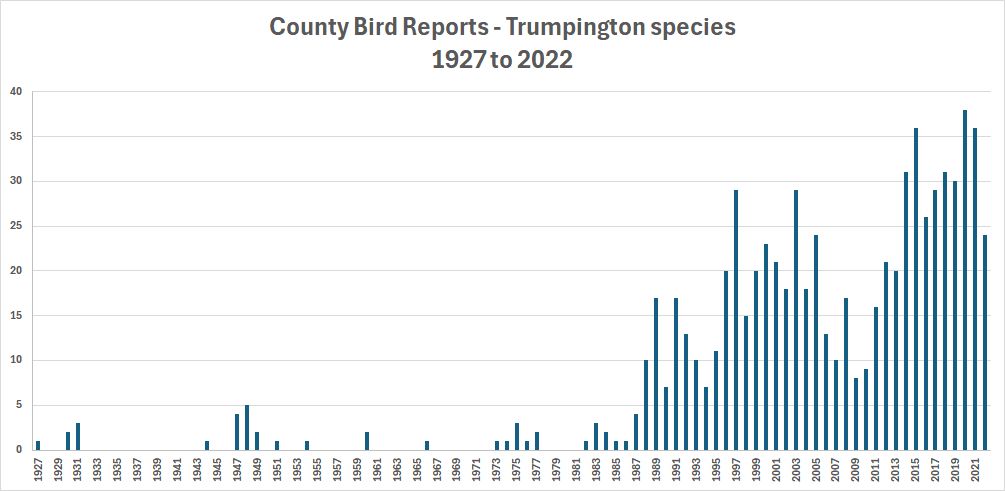

The Cambridgeshire Bird Club produced annual reports from 1927 onwards, part of which are dedicated to records of bird seen during the year. I have had fun going through these reports looking for mentions of Trumpington.

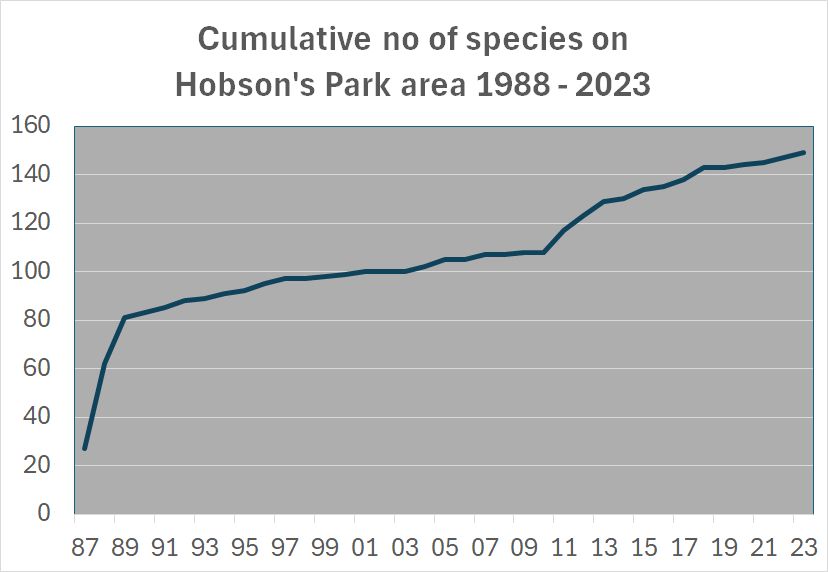

This graph shows how the number of species reported as having been seen here has changed over the years from 1927 to the present. You can see a general increase over time, with something of an explosion in the late 1980s.

This does not mean that the number of birds in Trumpington has actually increased as suggested. There are several explanations for why these changes have appeared:

1. Genuine change in populations: increases or decreases (if a species becomes rarer then it gets reported as unusual).

2. Observer presence (for instance when we moved to Shelford Road in 1988, I started to visit the farmland between the village and the railway looking for birds. Many of these records from 1988 onwards are mine.)

3. Thoroughness of the report: in 1929 there were just 5 pages of systematic records; in 2021 there were 118 pages, with much more on each page.

4. Modern technology can now help with identification and communication.

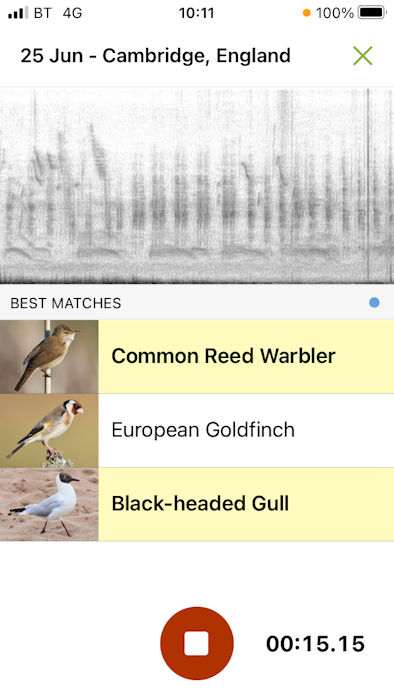

I have an app on my phone which does its best to identify bird species from their calls and song. However, a little knowledge can be a dangerous thing – non-birders have reported Bittern on Hobson’s Park and Grey Plover by the pond on Trumpington Meadows.

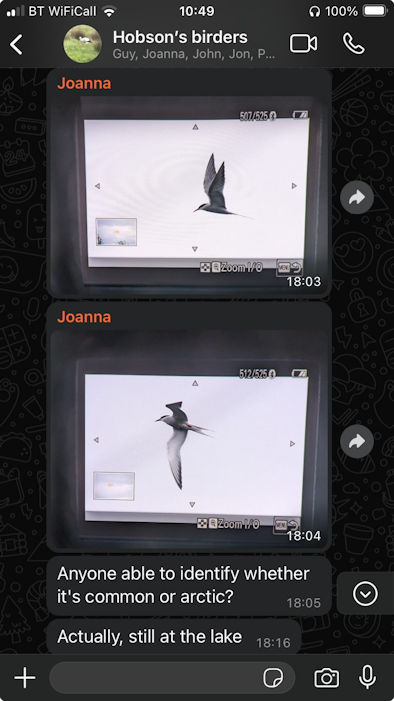

Modern communication (e.g. WhatsApp groups) help spread information. Gone are the days of me being out on the fields alone with my binoculars, reporting sightings at the end of the year to the county bird recorder. Now I can be sitting on my sofa when a WhatsApp message comes in telling me there is a Short-eared Owl on Hobson’s Park, and within five minutes I am watching it.

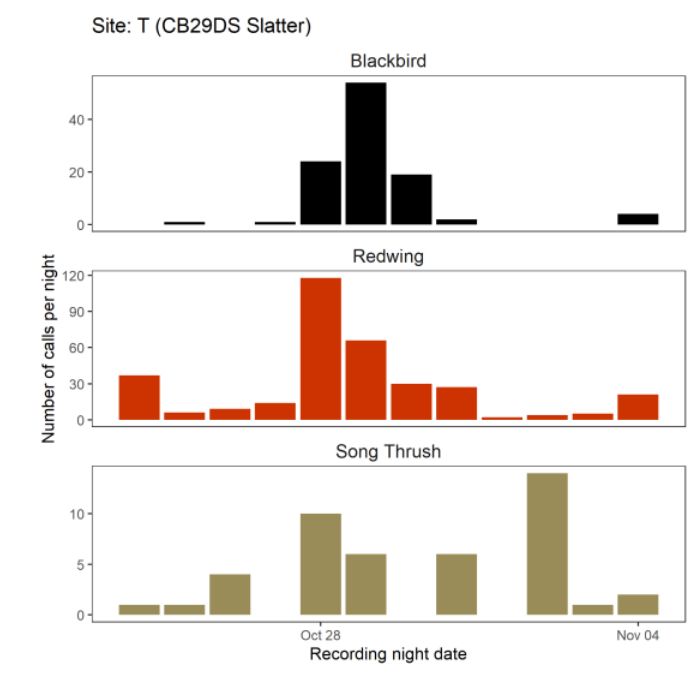

Technology can now help with the observation of nocturnal migration. It is now possible to put a small recorder out overnight, pointing at the sky, which records the sounds of birds flying overhead. Sophisticated software can then analyse the recording and tell which species were there.

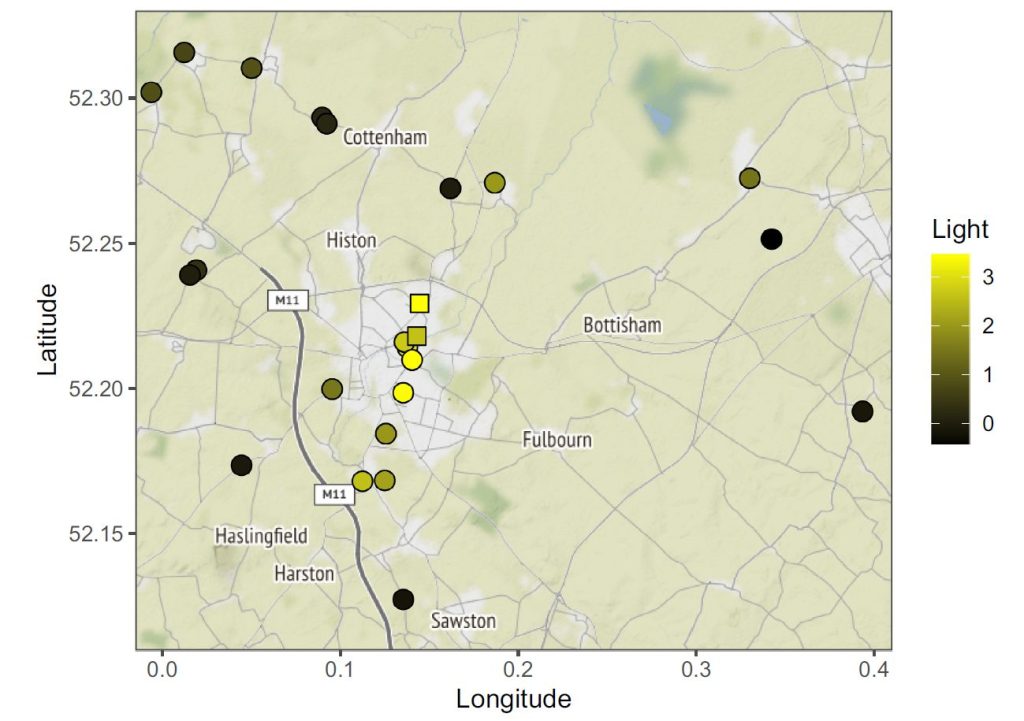

In 2019 Simon Gillings from the British Trust for Ornithology (BTO) organised a coordinated series of recording sites, each of which hosted a recorder for about two weeks in October and November, across the Cambridge area. This was to investigate the effect of light pollution on the flight patterns of migrating thrushes. The map shows the various sites, including three in Trumpington (one in my garden). The number of calls was recorded for each of the three species being monitored; this shows those flying over my garden.

Some records of interest:

Despite Trumpington not being on an obvious “flyway” (except for the Cam valley on the extreme west of the parish, which has been little watched until very recently) there is some evidence of a route at least for waders between here and Wicken Fen. A flock of 140 Bar-tailed Godwits flew over my head flying northwards in April 2007 and was later seen over Wicken Fen. And two Avocets left Burwell Fen (near Wicken) and two hours later two appeared over my house in April 2017.

Swifts are nationally in decline but artificial nest sites in both Trumpington Meadows and the Community Orchard are helping the population recover.

Some species are spreading, for example: Collared Dove (first breeding in Cambridgeshire in 1961), Canada Goose (first breeding in 1959), Sparrowhawk, now returned from extinction!

I have been recording the numbers of each species seen by me when out on the fields/Hobson’s Park since 1988. My observations do not pass any of the tests for a real “survey”: different lengths of time out, different times of day, different routes, slightly sporadic visits (though I try to get out once a week). However, they do paint an interesting picture.

This graph shows how many species I have recorded, in total, on my “patch” over the years. After an initial adding of common species, I then slowly added new species year by year, going up from about 80 in 1989 to 110 in 2011. Then the number starts to increase considerably, coinciding with the transition from farmland to residential development and the new habitats created by Hobson’s Park. The number is still growing, and now stands at 150.

Some species have particularly interesting stories to tell.

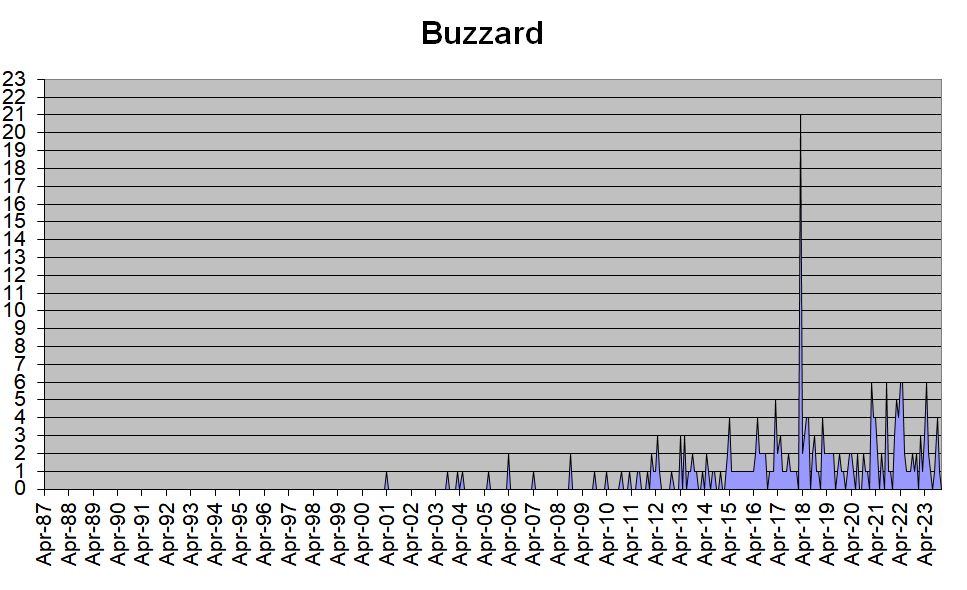

Buzzard was absent from here until 2001, and then started to appear as the species recovered from persecution. They are now commonly seen, and breed locally.

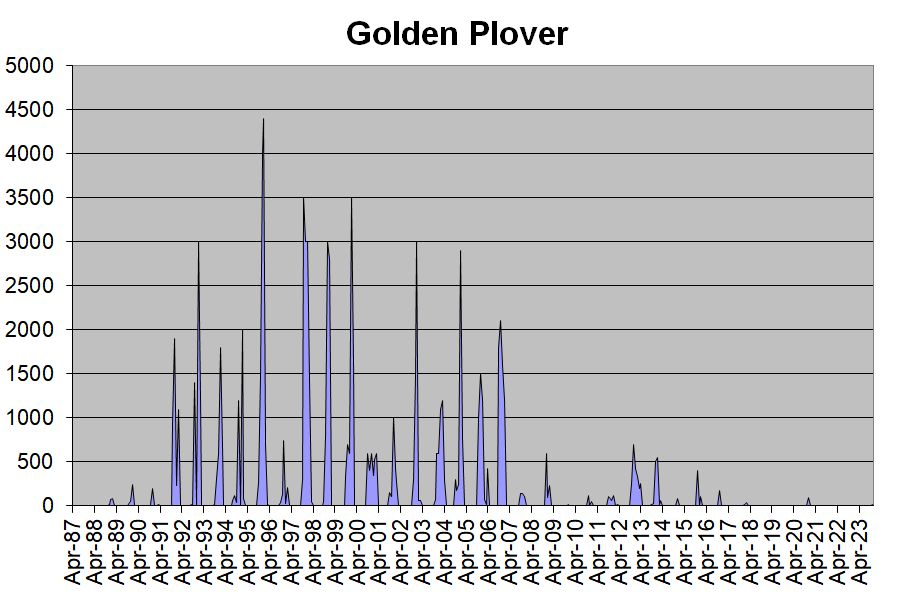

For 15 years from 1992 onwards there was a large (up to 4000) wintering flock of Golden Plovers on the farmland. Since the conversion to Hobson’s Park, they are rarely seen except in the distance.

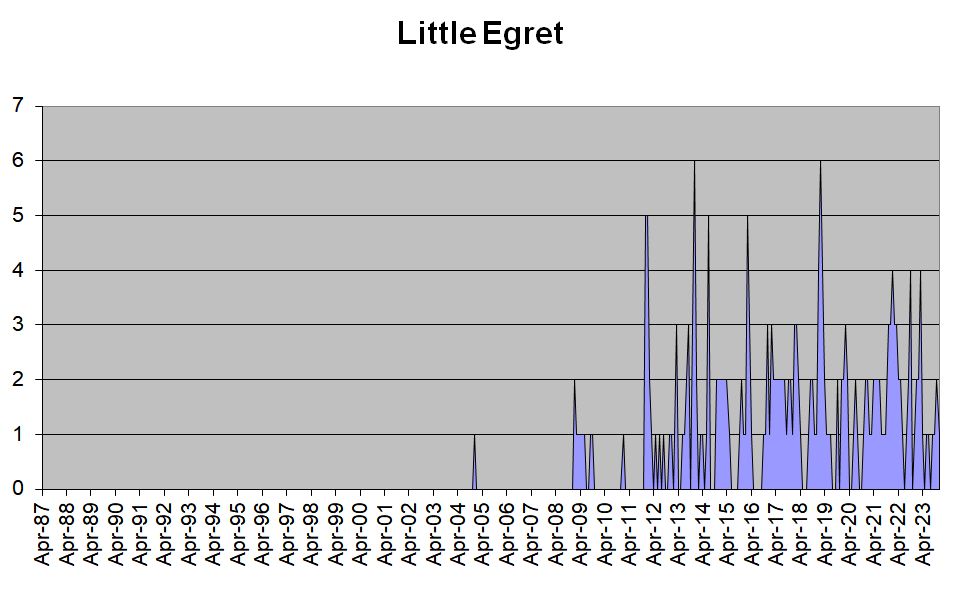

Little Egret was unheard of until this century. Now, as part of their northward expansion, probably driven by climate change, they are a common sight, though not yet breeding in Trumpington.

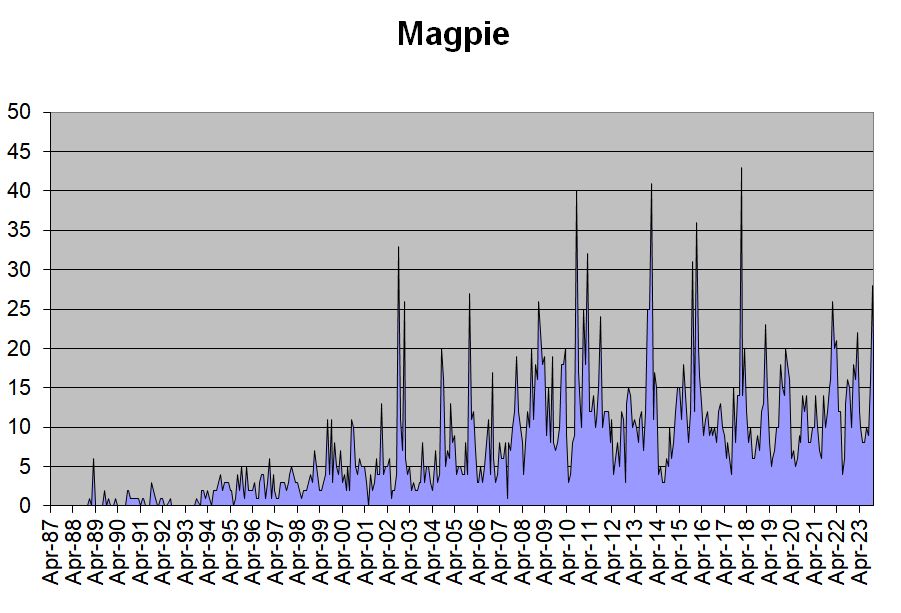

Magpies were few and far between until the mid-1990s. Double figure counts are now the norm, with a roost in the tree belt beside Hobson’s Brook each winter holding over 20 birds.

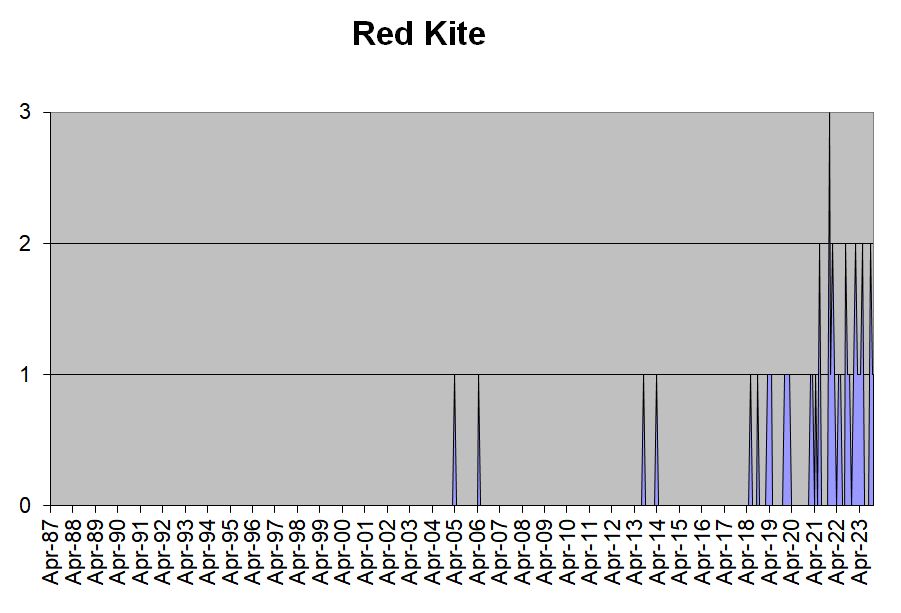

When I was birdwatching in the 1970s, we had to visit a small area in central Wales if we wanted to see a Red Kite. There have been several re-introduction schemes since then, including one in Northamptonshire, and now they are commonly seen overhead here.

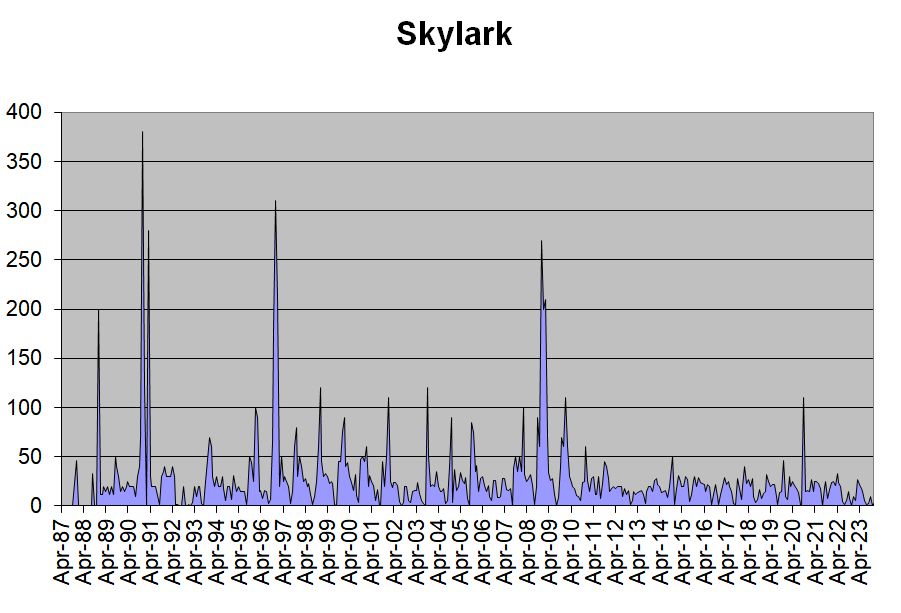

Skylark has always been fairly common on the open spaces locally, though not as much as in the 1850s. Wintering flocks (when they are easier to see and count) have numbered 200 or more on several occasions during my recording period. The national population, along with that of several other farmland species, has declined considerably over the last few years, but the breeding birds here seems to be holding up fairly well.

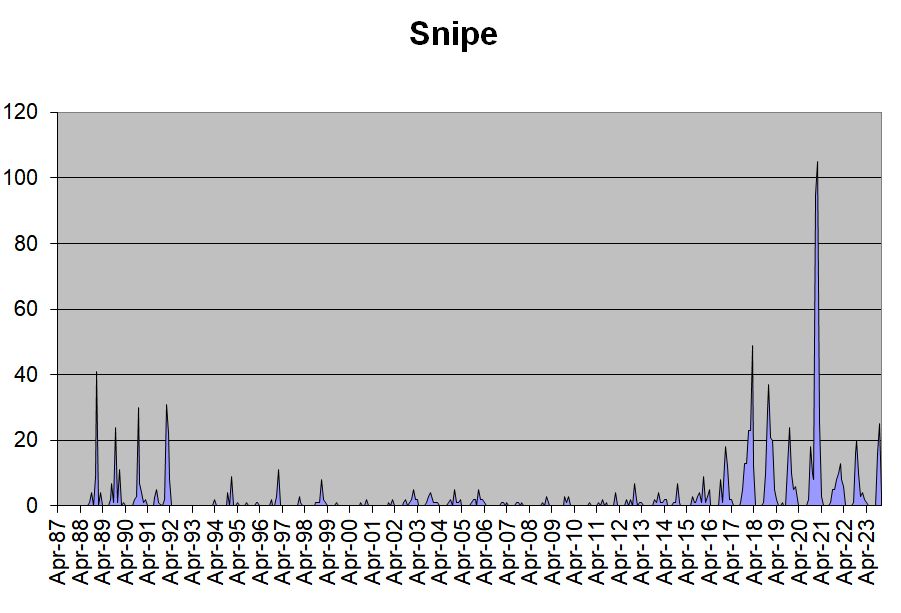

Common Snipe were seen on the still undrained bits of farmland in the winter when I first started recording here. Then, after drainage, they almost disappeared. Now they are a regular winter feature of the big pond on Hobson’s Park. In the winter of 2020-21, when the water level rose unusually high because of a blocked outlet pipe, there were over 100 present.

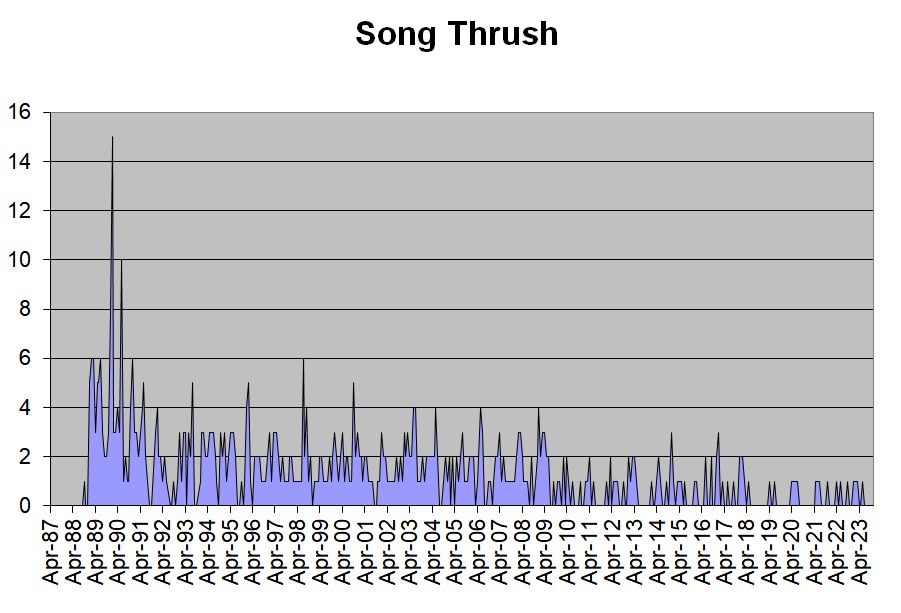

Song Thrush has steadily declined, in keeping with national trends.

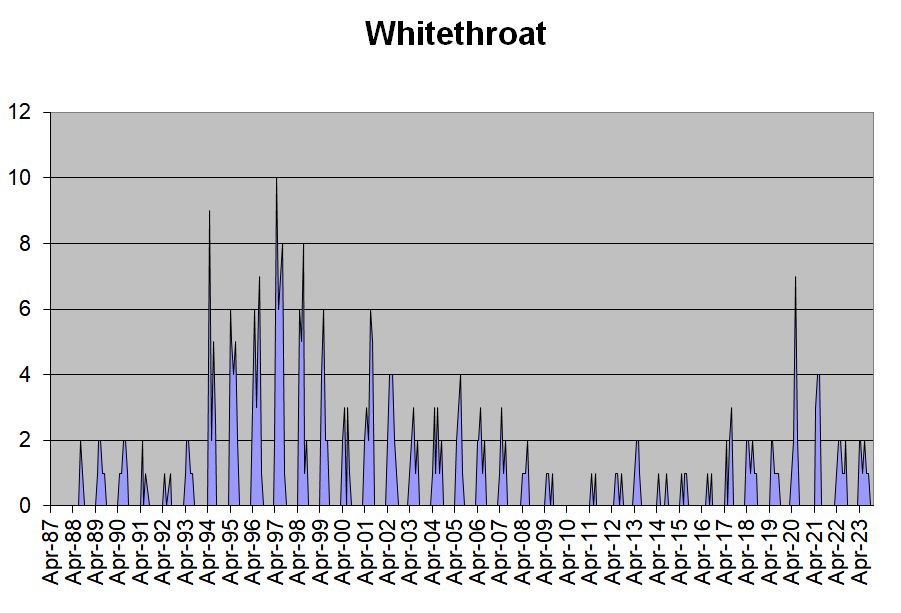

Whitethroat became quite common in the 1990s as the new tree planting along the old railway line and Hobson’s Brook started to mature. Eventually those trees became too big, and the population disappeared by 2010. However, the creation of suitable new habitat on Hobson’s Park has led to the return of Whitethroat as a nesting species.

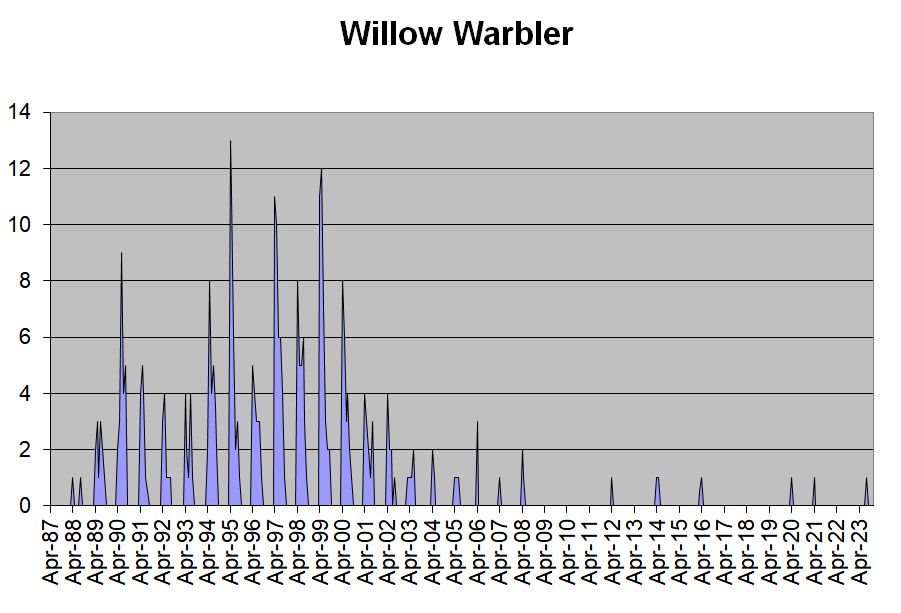

Willow Warbler shows a similar pattern to that of Whitethroat, but has not recovered, in line with a national trend of movement north and west.

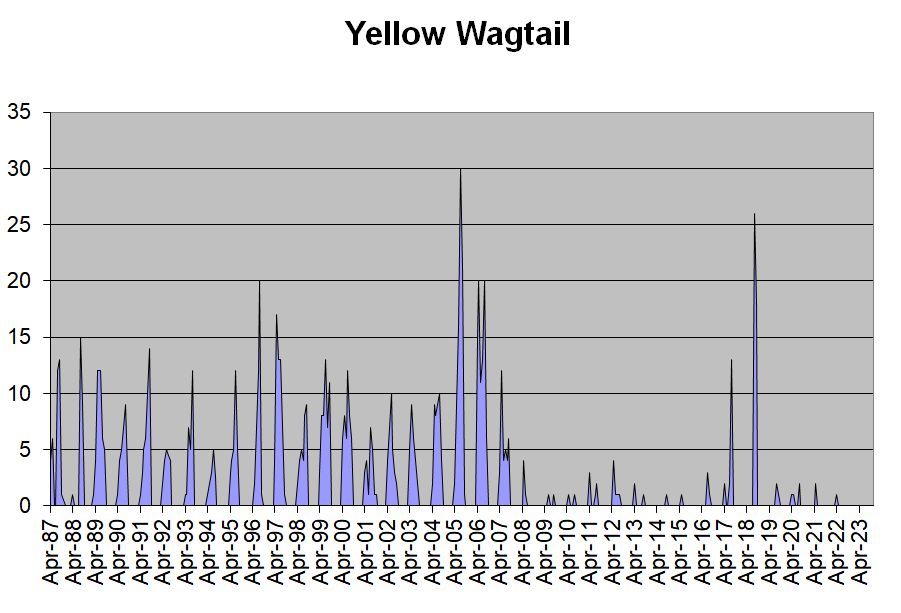

Yellow Wagtails breeding in the crops were a prominent feature of the farmland up to 2007. Since the cessation of farming, though, they now only appear occasionally on passage.

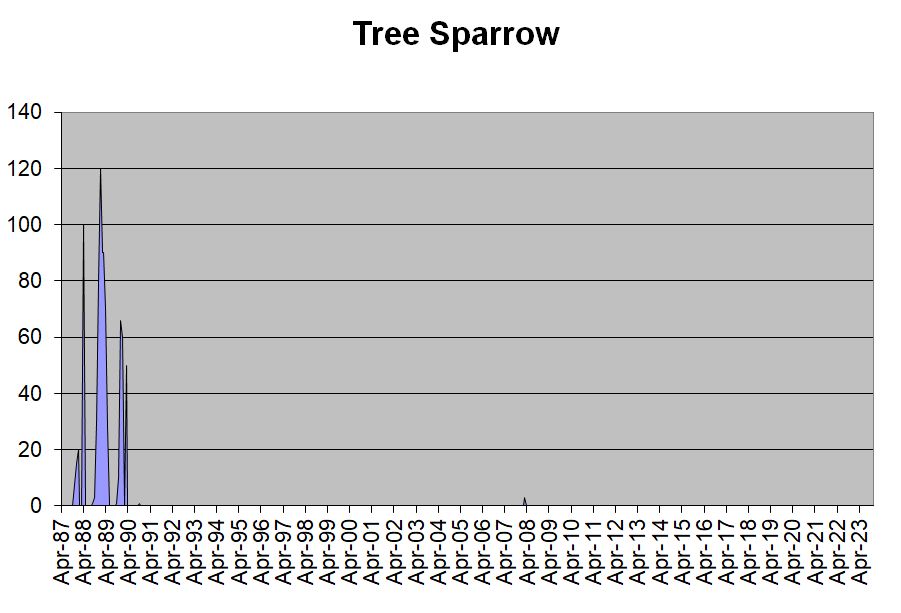

Tree Sparrow is another species whose national population has crashed over the last 30 years. We had a wintering flock here up to the 1989-90 season, but I have only seen two birds since then.

Acknowledgements

I am indebted to several people for information they have provided, and to others for permission to use their (local) photographs.