Pamela Stacey

In 1982, I enrolled for the three-year Vice Chancellor’s certificate evening class which was run by the University of Cambridge Board of Extra-Mural Studies at Madingley Hall. Roland Randall and Erica Towner were the course tutors. The first two years consisted of evening lectures, some field trips and written work. In the third year, those of us who wished could continue and do our own original field study which would be examined externally and, if successful, the Vice Chancellor’s Certificate in Landscape and Ecology awarded. Roland suggested I should do a study of the disused railway line in Trumpington as it had an interesting flora and importantly to me it was very near to my home in Bishop’s Road.

This is an edited version of my report. The species lists for each site, the site details and the references have been omitted but are referred to in the text.

At the time of the study, 1984-85, the railway line had been disused for over 15 years. It continued in this state until 2008-09, when it was repurposed as the route of the Cambridgeshire Guided Busway to and from the Trumpington Park & Ride terminus. Many of the plant species continue to grow but some others have been lost. The area has become a site for badger setts which were not present at the time of my study.

All text and illustrations are from the Study.

Pam Stacey edited the original text in June 2021 and this page was added to the web site in December 2023.

A Study of the Flora of the Disused Railway at Trumpington and factors which may cause this large variety of vegetation, 1984-85

Introduction

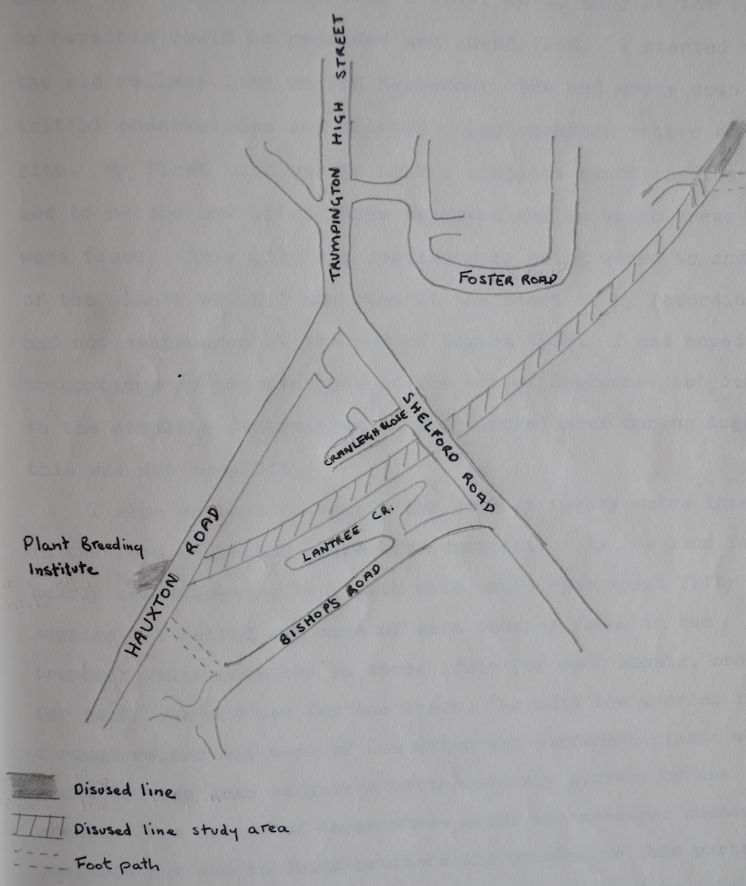

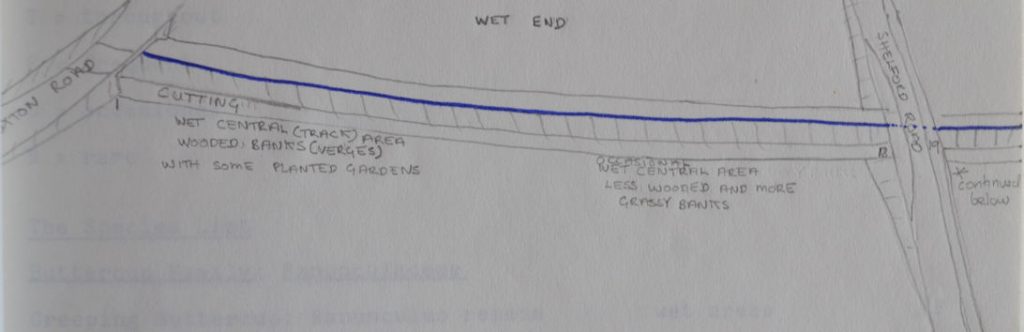

The railway line going from Cambridge to Bedford was closed on 8th December 1968 and the track has since been removed. For this study I decided to use the length of disused railway extending from the Hauxton Road bridge (where it leaves the Plant Breeding Institute), to where the footpath crosses the line from Foster Road, Trumpington (Fig. 1). This seemed to be a reasonable area to use as it starts off as a cutting with trees around the banks and then gradually the banks become less steep and eventually flatten out completely. The result of this variation of form is a wooded, wet, shady part which alters to a drier more open area, and then to a very dry track with grassy meadow-like verges. There Is also a small stream which runs from the Plant Breeding Institute grounds along the base of the south facing bank for about 500 metres and then comes to an end as the pipes carrying the irrigation water are intact from this point onwards. So, this provides an even wetter habitat for some of the plant species. As well as this variation in wetness, availability of light and soil-change, man also plays a large role in deciding the flora. This can be seen in several ways as he tramples some areas, introduces new species in the form of gardens or garden escapees, and generally interferes by dumping soil and waste materials. These were the main factors which I have considered in this project as I made a study of the flora.

Materials and Methods

To carry out a detailed study of the flora this investigation had to take place over a year, so as many of the plants as possible could be recorded and identified. I started visiting the old railway line on 3rd September 1984 and wrote down initial observations and started a photographic record of the site. My first task was to make a complete plant species list and to record how often these appeared and in which areas they were found. This list was continuously being added to and some of the plants which I had seen at the start of my recordings had not reappeared at the end of August 1985. I had hoped to continue my observations to the end of September but due to the complete destruction of the central area during August this was not possible.

I also decided to sample the site at twenty metre intervals in the form of a half metre wide transect. As the line is nearly one kilometre in length this would give about fifty samples. A record was made of each species found in the transect which resulted in three lists for each sample, one for each bank and one for the track. As with the species list a rough record was kept of how often the different plants were found in each area to give a better overall picture of the sample. The length of these three areas was measured whenever possible but due to thick hawthorn and bramble in some parts, and the stream in others this could not always be done. In these unclimbable areas the plants were identified from afar but often only a few species were present due to a good covering of ivy or bramble. The first transects were taken during May as by then a reasonable number of plants were growing and could be identified, whereas later in the season many would have been buried by larger quick growing plants, such as stinging nettles and impossible to find (photograph 85).

This was particularly true of the first samples as the plants had to emerge from last year’s leaf litter and were soon covered by tall nettles, great willowherb and hogweed (photographs 53, 54, 74). The final transects were carried out in the middle of June but as they were in the meadow end of the line, it was still fairly easy to recognise the plants (photographs 76, 77). All the sampling sites were revisited several weeks after the initial recording to modify the species found, as some new plants would have grown and some would have been wrongly identified. This all came to an abrupt end during August as previously mentioned, so no more sorting out could take place. The track area had been flattened so only bare soil remained, and the stream had lost all its plants and was full of cloudy water with no animal life surviving.

Results

1. The Species List

As the main book which I used for identification was The Wild Flower Key by Francis Rose (Warne, 1981), I decided to present the species list in the same form and order as that book. Any species not included in the Key were inserted at the most suitable place. I have also added to some of the plants short comments about habitat and their frequency. The comments refer to different parts of the railway track and verges which can be seen in the diagram. The frequency has been simply divided into rare, occasional, frequent and throughout.

2. The Sampling Sites

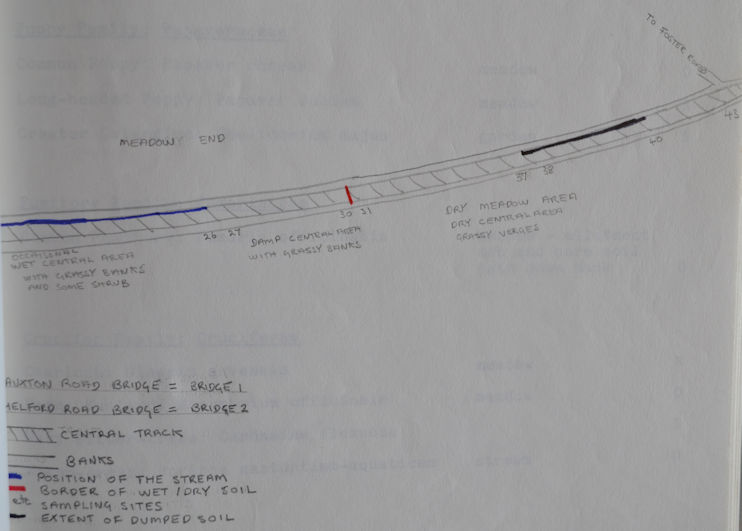

The first sampling site was near to the Hauxton Road bridge (bridge 1: Fig. 2) and the remaining samples were taken at twenty metre intervals. Separate lists were made for the banks and the centre area, and each sample was a half metre side transect. A quantitative record of the frequency of the plants found was recorded. Altogether there were forty-three transects, the final one was just before the path from Foster Road which crosses the railway line and the arable land to Robinson Way at Addenbrooke’s Hospital. These results are presented on a separate sheet for each sample with a simple outline drawing of the transect with the plant species found written above the appropriate area. These lists are in alphabetical order with a simple coding for the frequency i.e., 1 – 4.

1 = only one or a few plants found

2 = several plants

3 = nearly everywhere

4 = complete cover.

Additional comments were added to some of these sheets when there were points of interest. Several grass species were found but as they were at an early growth stage when most of the sampling was carried out, they only appear as grass on the result sheet (see Appendix A).

3. The Photographic Record

The photographs have been placed within the text and included below.

Discussion

Factors which may play a part in deciding the flora of the area

The disused railway line at Trumpington is a species rich area as over two hundred different plants were recorded. Some of these species were found throughout the site, whereas others only occurred once or twice. This diversity of flora seems to be partly related to the marked change of form of the line over a short distance. As one goes along the line from Hauxton Road it gradually becomes more open, flatter, and drier. Some of my sampling sites had wet central areas throughout the year even when there had been no rain for several weeks, likewise the dry sites were always dry. Obviously, the area around the stream is damp but other wet areas were often found at the base of the opposite bank, so plants such as water figwort and great willowherb were found growing there. The stream is river water which has been piped across the Plant Breeding Institute grounds, along the base of the south facing bank to provide water for irrigation of the arable fields beside the track. These pipes broke in several places and the stream formed, so some of the wetness of the soil is due to flooding and other wet areas form as rainwater collects in various wheel tracks. This still does not explain all the wet sites so perhaps some are due to water draining out of the banks where houses have been built. There is a distinct line across the track which marks the change from damp soil to dry ground (photograph 92). Before this boundary line toad rush manages to grow but after the line is it absent.

The soil in the region of the old railway line is mainly gravelly and there used to be gravel workings in the area which is now Cranleigh Close. Also, the original settlement of Trumpington grew up around the gravel beds beside the ford which crossed the stream. This was the crossing point for travellers who wished to go from the Fens to the Midlands as the River Granta was difficult to cross elsewhere. The gravel can be seen where the bank is exposed and has fallen into the stream making a shallow area (photographs 7, 8). At the wet end of the line there seems to be almost clay-like soil but this may be due to the flooding of the stream, or general earth moving such as when the bridge to the Plant Breeding Institute was blocked, and when the line was originally excavated. After the destruction in August by the diggers which were preparing the track for the gas pipe laying the soil was clear of plants and exposed. The sides of the stream were cleared out and dumped at the base of the other bank which showed some small gravel stones, and as it was wet for the following week water-cress was managing to grow here. Some areas were very wet as the heavy machinery used had made deep tracks which had become waterlogged so as before the wetness gradient was easy to see (photograph 10). This disturbance also revealed more clinker and ballast, as well as a patch of sand. There was also one sleeper in the centre which had been left behind when the others were removed.

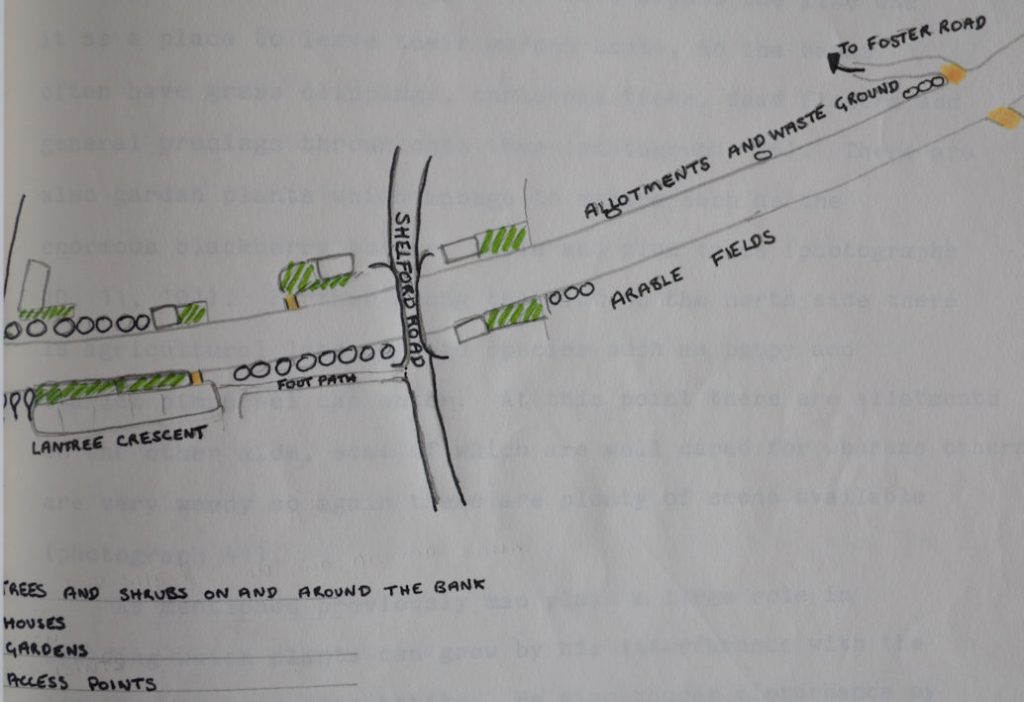

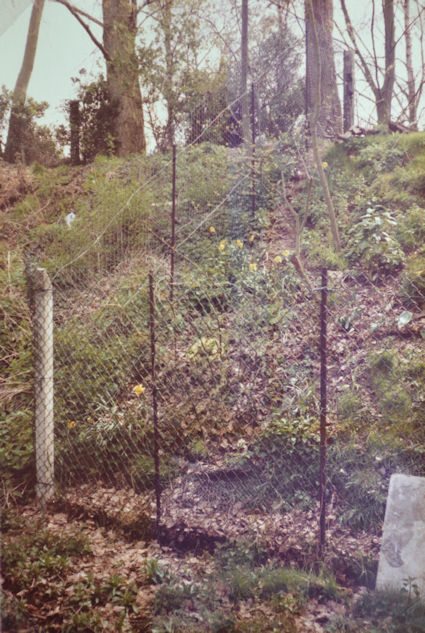

Another factor which helps to decide which plants are present is the surrounding land use (see Fig. 3). Starting at the first site, the Hauxton Road bridge area, which is in a residential area with gardens on both sides, some of the house-owners have bought the piece of bank which connects up to their gardens and planted garden species (photographs 4, 50), while others have just cut down the trees (photographs 51, 52). This accounts for some of the garden species in my list (garden), whereas others such as old potatoes (garden?) were dumped. In this same area (Lantree Crescent) much dumping of rubbish used to occur, such as old carpets and wood. Also, there were several burning sites in the central area which left a supply of ash and bare ground for new colonisers such as common nettle (photograph 84). Many people who live around the line use it as a place to leave their garden waste, so the banks often have grass clippings, Christmas trees, dead flowers and general prunings thrown onto them (photograph 26). There are also garden plants which manage to escape such as the enormous blackberry bushes, apple and plum trees (photographs 10, 11, 101). Further along the line on the north side there is agricultural land so weed species such as poppy and scarlet pimpernel can enter. At this point there are allotments on the other side, some of which are well cared for whereas others are very weedy so again there are plenty of seeds available (photograph 41).

As mentioned previously, man plays a large role in deciding which plants can grow by his interference with the line by his gardening habits. He also causes disturbance by climbing up the banks as there are several entry points, this may leave clear soil and new species such as parsley-piert can grow (photographs 8, 9, 36). Some of the vegetation around the stream has been cleared away, this was presumably to allow children a better access point to view the water life (photograph 86). The area is also used by people walking from one part of the village to another, and then across the fields to the hospital (photograph 40). Many dogs are taken for their walks along there and of course provide a source of nutrients as they go. Children use the line as a play area and some ride up and down on their motor cycles. Joggers and horse-riders also use the track and mothers bring their children down to the stream as a safe place to observe the sticklebacks. In the autumn more trampling occurs as people come to collect the vast supply of large blackberries. I also knew of one local resident who throws his old garden seeds down the track but I do not know if any of them ever manage to germinate. Perhaps he is the same person who dumped the yellow loosestrife plants which are growing.

Much soil was dumped on the track before my first visit last September (1984), the same event occurred this year. This soil was used to block the entry point from Foster Road to prevent any Midsummer Fair followers using the track. As soon as the fair is over this soil is removed from the gateway and spread out on the track (photographs 16, 20, 37, 38). This introduces many seeds with the soil which soon grew in the following spring (photograph 83). The children used this dumped soil and rubble extensively as a play area during the autumn and early winter, but most of the rubbish had been cleared away by the spring and the plants quickly grew and covered the soil in the summer. The species present were typical garden weeds such as wall barley, pineappleweed, fool’s parsley, black nightshade and annual nettle. Much of the dumped rubbish which had built up over the year was removed from the railway line during the early summer, it now seems that this may have been in preparation for the gas pipe. This brings us to the extreme factor deciding the species present as many which I had earlier recorded are no longer visible. As I have previously mentioned it seems that the sides of the stream were scraped and the soil dumped at the base of the opposite bank. Also, the rest of the central area was flattened and in many parts the soil turned (photographs 105, 106). This suggests that many of the plants are still there but buried so perhaps little soil was actually removed. Some plants such as the crack willows must have been removed so there is no sign of them. As it was very wet after this flattening many of the plants were trying to grow back again, especially the grass, colt’s-foot and willows (photographs 103, 104).

During the past month, the pipe laying has started and seems to be taking a long time. The damage done increases daily, the central area becomes more and more churned up with deep ruts from the large heavy vehicles (photograph 111). The materials being used which include several piles of sand as well as the pipes have been dumped at the base of the bank, damaging the plants growing there. Large branches have been broken off the hawthorn and ash which had escaped damage earlier. So, in general the banks which had been fenced off by the stakes and rope are now being threatened. I have referred to the water running along the base of the bank as a stream which would perhaps suggest that there was more volume than there was as it was only a few centimetres deep where various obstacles had fallen in. However, the pipe layers have certainly brought about a change, they have several pumps which are moving the water to the dry end (photograph 114). They have exposed some of the original pipes at this end and the water is pumped into them (photograph 116). Metal sheets have been sunk into the stream which is now very cloudy. The main difference which they have brought about is the widening of the stream at the wet end (photograph 112). In some parts it is now so wide that there is more water than land and it seems to be fairly deep but as the water is so clouded it is not possible to see clearly. Luckily the past few weeks have been very dry, otherwise the track would be all water in some places and I would be writing about the formation of the River Trumpington.

The final factor which may play a part is aspect as regards the banks of the verges. The line runs roughly from west to east giving a north and a south facing bank. This is not a true north/south as the line curves around so by the time it becomes open at the meadow end the banks do not face true north or south. They probably receive an equal amount of sunshine and in general the species found did not vary much from bank to bank. The area which is more north/south is where the embankment is and the sides are covered with trees and shrubs so it is shady and little sun enters once the leaves are out. The only differences found were cowslips, lady’s bedstraw and meadow saxifrage which grew on the partly north facing bank of the meadow end, and giant lettuce with hairy sedge on the south facing bank (photographs 61, 72, 90). Aspect may be deciding which bank they grow on but it seems that it may just be chance.

Some of the fauna of the disused railway line

As can be seen by looking at the results there is a rich species of flora present along the line which means that it should also give a good site for animal life. There is a vast ant colony which extends along the banks at the meadow end. These are the yellow field ants, Lasius flavus, which are common in grassland and can exist for centuries, but of course I cannot say that these have been there for that long. Many years ago, the land around here was grassland used for sheep grazing and more recently it was well fertilised to prepare grass for the Royal Agricultural Society’s showground and then returned for arable use. Where the ants are present the soil is very aerated and loose, in fact on climbing up the bank it is the way which your feet move that makes you realise that you are standing on an ants’ nest. Their action must give a good drainage to the soil but as the ant colony is on a bank this already has fairly dry soil. They also expose patches of earth which allow new plants to grow and they may even bring seeds up to the surface which can then germinate (e.g., wild carrot and common mouse-ear).

The banded or striped snail, Hellicella cernvella virgata, is another common sight especially on sunny days as the snails climb up the plant stems of the meadow end banks. They were mainly a very pale pink colour with pale brown bands. I have since seen some which are much browner and some which are a deep orange/pink. There are others that are completely white or white with an almost black band. In general, it is the paler coloured ones which climb up the plant stems, perhaps they reflect more light and keep cooler, as this is probably why they left the soil in the first place. They do not climb the stems on dry or windy days as this tends to dry them up. Snails can easily be found on the damp soil under the moss at this time of the year. Railway embankments are supposed to be one of their preferred habitats. Many broken snail shells can be found on the stones of the dry central areas, which have been left there by thrushes. It is quite common to follow several thrushes going along the track searching out the snails.

On cool damp days or early evenings many large black slugs, Arion ater var ater, can be seen. These are particularly found on the lower grassy areas. In the spring large groups of metallic bluey-green leaf beetles were seen feeding on the great willowherb leaves. Ladybirds, Adalia spp, and froghopper larvae, Neophilaenus Lineatus, in the form of ‘cuckoo spit’ were found on the plants. Soldier beetles, Rhagonycha fulva, collect together on the wild carrot. Dragonflies, odonata, fly around the stream and bees find many flowers to feed on (photograph 79). The dog-roses and field-roses provide a site for the gall-wasp, Diplolepis rosae, to lay her eggs which produce ‘pincushions’ in the late summer (photograph 117). On sunny days many butterflies were on the wing, orangetips, Anthocharis cardamines were the main ones in the spring with some whites, Pieris spp; common blues, Polyommatus icarus; small skippers, Thymelicus sylvestris and small coppers, Lycaena phlaeas. Later in the year there were mainly meadow browns, Maniola jurtina; hedge browns, Pyronia titbonus, with small tortoiseshells, Aglais urticae and small skippers, Thymelicus sylvestris (photographs 98, 99). As the area provides several good stinging (common) nettle sites the black caterpillars of the peacock butterfly, Inachis io, had a plentiful food source. During the day cinnabar moths, Tyria jocobaeae, were seen flying around the ragwort, which later became the food supply for their caterpillars. Many small moths were seen flying around the track in the early evening. The caterpillars of the elephant hawk moth, Deilephila elpenor, ate many leaves of the rosebay willowherb, and the caterpillars of the buff-tip, Phalera bucephala, completely stripped the leaves of the goat willow on which they were feeding (photographs 15, 21).

Frogs, Rana temporaria, would frequently jump out of the vegetation on the bank, when this was being climbed. In the spring large numbers of tadpoles had been seen in the stream and in the flooded wet areas of the wooded end. There was much life in the stream especially caddis fly larvae, Limnephilus spp, which could be seen crawling along the bottom in such numbers that they gave the impression that the floor was moving. Sticklebacks, Gasterosteus aculeatus, and minnows, Phoxinus phoxinus, were found in all parts of the stream and swam around the various metal objects which had been thrown in the water. Freshwater shrimps, Gammarus pulex, could be found under stones and on any floating bits of wood. Water beetles (coleoptera); water boatman, corixa punctata, and water snails, Lymnaea spp, were also present. Pond skaters, Gerris spp, were often on the water’s surface and these were the only major survivors after the dredging. On visiting the site a few weeks after the initial damage by the workmen, the stream had settled, giving clear water again, and I saw one snail, one fish and one water shrimp. Since then, it has been completely unsettled with all the pumping so it is very cloudy and the only animal life visible was on one side of the stakes which I presume the children had thrown in, which had been colonised by over fifty freshwater shrimps (photograph 115).

As mentioned earlier, many thrushes, Turdus philomelos, use the line as a good snail supply and they also eat the berries in the autumn. The other common bird of the railway line is the goldfinch, Carduelis carduelis, which flies around the meadow end, perhaps to feed on the thistles.

In general, it can be said that there is a wide variety of animal life present who use the varied food source available. As the vegetation is so varied it also provides many different sites for shelter and nesting, such as the trees and grassy verges. Many other animal species use the disused railway line but I have only mentioned those which are so obvious that you do not have to look for them.

Possible changes to the surrounding region

During the time which I have been studying the flora of the old railway line there have been several threats on the area. The first occasion was when the old idea of the ‘railway’ road was reborn at the time of the local County Council elections. This was a most unpopular idea and caused much local ill feeling towards the Conservative councillor, and many letters of protest were sent to the newspaper. One of these letters suggested that the track should have a proper entrance and be maintained as a nature reserve. Local residents who had purchased the railway banks as an addition to their gardens certainly did not want to lose them. In fact, one owner followed me to find out what I was doing as he had spotted my measuring tape when I was sampling. This idea of the road has now been abandoned again as it was too costly, destructive and very unpopular.

The proposed change in the Green Belt around Cambridge may affect some of the line, and create more pressure on the wildlife. This involves the area of Clay Farm and extends to the allotments and again it is extremely unpopular with the local residents. A large number of signatures were collected in protest as people do not want the village character to be spoiled and a large green area to go, with continuous development with Cambridge.

The final major threat is the British Gas Company who are laying their pipeline now. This is to supply gas to some of the villages but it also passes through Grantchester, where there is still to be no gas. I have already described the damage caused to the track, stream and lower bank with the destruction of all the living matter. As the weeks go by more and more disturbance occurs. Some areas go from wet to dry, to very wet, and the soil is continuously being churned up by the various heavy vehicles being used. Once the work has finally come to an end the soil should be left fairly flat, so there will be most of the autumn followed by the winter as a time for settling and then hopefully many seedlings will appear during the spring.

Conclusions

Many naturalists look upon Beeching in a very favourable way, remembering him as the man who upon closing so many railways opened so many linear nature trails. As soon as they were disused, they became ideal sites for plant invasion and as many were left undisturbed rich floras resulted. Some of these railway lines have disappeared into the surrounding farmland, others are completely overgrown. Some are used by local residents while others are nature reserves which are looked after by the local council or naturalist trust. These lines with their tracks and verges provide many habitats for a wealth of wildlife over a narrow and sometimes short distance. They can alter from a wooded, shady, damp cutting to a flat open area and then sometimes up onto an embankment which is more exposed and drier. The old railway line at Trumpington which has been studied, passes from a cutting which has mainly ivy-covered banks with many small trees with a wet shaded track where only a few different species can grow. It then gradually flattens out with less of a bank with open countryside consisting of allotments and arable fields surrounding it. Then finally it becomes more meadow-like with gentle grassy banks and a very dry central track. So, this site has a lot to offer in terms of habitats and I hope I have managed to demonstrate this with my results from this year long study. It was very upsetting when the gas pipe laying was, and still is, taking place, but hopefully the richness of plant and animal life will soon be able to recover. I have contacted Mr Pemberton, who is the principal landowner of the site, and he intends to let the plants grow back again and is quite happy for amateur naturalists to use the railway line. He originally bought the land for irrigation purposes and introduced the stream, and initially tried to keep the track clear but he found this to be impractical due to the wetness and the dumping which occurred. So about seven years ago he decided to let the track go back to nature in an attempt to control both the wet soil and the dumping of waste. It would seem that much should grow back fairly quickly as the plants had only had a few years to grow before; but of course, the damage done is much greater this time.

It will be very interesting to follow the recolonisation of the track and to see which of the old species manage to reappear and which new ones will be able to utilize and grow on the bare soil. Perhaps some of the plants will be more widely distributed as any differing soil areas are now much more mixed, and also a fair amount of sand has been introduced by the pipe layers. At the moment it is not possible to see what is happening to the stream as so much of the water is being pumped around. It would be advantageous for the site if the stream remains in some form, as it had so many associated plants and animals which without the water would not be able to colonise the railway line. Over the past year I have found the old railway line at Trumpington a very interesting site, and I have identified several plant species which I had not known or seen previously. So, I hope it will continue to be used as a quiet place to walk and look at the many different plants and animals, as well as a site for further investigations by ecologists.

Acknowledgements

I am indebted to Roland Randall and Erica Towner who enthusiastically supervised the Ecology and Landscape course. I would also like to thank The Eastern Region, British Rail Property Board for railway information, the Trumpington Farm Company who own the base of the old railway line and Anthea Hills for typing.

References

Omitted from this version.

Appendix A

A check list of the species recorded at the sampling sites.

alkanet

apple

ash

aspen

bindweed, field

bindweed, hedge

bittersweet

black-bindweed

black medick

blanket weed

bramble

brooklime

bryony, white

buddleia

buttercup, bulbous

buttercup, creeping

campion, bladder

campion, white

cat’s-ear, common

chickweed, common

cinquefoil, creeping

cleavers

clover, red

clover, white

colt’s-foot

corn mint

cotoneaster

cowslip

crane’s-bill, cut-leaved

crane’s-bill, dove’s-foot

currant, black

currant, red

daisy, common

daisy, oxeye

damson

dandelion

dead-nettle, red

dead-nettle, white

dock, broad-leaved

dock, curled

dog-violet, common

dogwood

duckweed, common

elder

fat-hen

feverfew

fleabane, Canadian

fool’s watercress

forget-me-not, field

forget-me-not, water

fumitory, common

garlic mustard

goat’s-beard

grass

ground-elder

ground ivy

groundsel

hairy tune

hawk’s-beard, beaked

hawk’s-beard, smooth

hawthorn

hazel

hedge mustard

herb-robert

hogweed

holly

horsetail

iris, garden ivy

knapweed, common (black)

knapweed, greater

knotweed, Japanese

lady’s bedstraw

lamb’s lettuce

lettuce, great

lettuce, prickly

lichen, yellow scales

mallow, common

mayweed, scented

meadow saxifrage

moss, compact

moss, stalked

mouse-ear, common

mullein, great

mugwort

nettle, common

nettle, small

nipplewort

parsley, cow

parsley, fool’s

pineappleweed

plantain, greater

plantain, ribwort

plum

poppy, common

potato

privet

ragwort, common

raspberry

redshank

reed, common

rose, dog

rush, jointed

rush, toad

scabious, field

sedge, hairy

selfheal

shepherd’s-purse

sorrel, common

sow-thistle, prickly

sow-thistle, smooth

speedwell, field

speedwell, germander

speedwell, ivy-leaved

speedwell, wall

spurge, petty

spurge, sun

strawberry, wild

sycamore

toadflax, common

thistle, creeping

thistle, spear

trefoil, lesser

vetch, common

vetch, tufted

violet, sweet

water-cress

wavy bitter-cress

wild carrot

willowherb, great

willowherb, rosebay

yarrow yellow loosestrife

Site descriptions

Omitted from this version.

Photographs

Photographic record of the disused railway line at Trumpington, September 1984 – September 1985, plus winter 1994. All photographs: Pam Stacey.

Photograph 1-19, 3 September 1984

Photograph 20-26, 30 September 1984

Photograph 27-40, 8 December 1984

Photograph 41-47, 24 March 1985

Photograph 48-68, 28 April 1985

Photograph 69-72, 28 May 1985

Photograph 73-75, 30 May 1985

Photograph 76-78, 15 June 1985

Photograph 79-83, 2 July 1985

Photograph 84-93, 13 July 1985

Photograph 94-110, 21 August 1985

Photograph 111-118, 22 September 1985

Photograph 119-127, winter 1994