At the Local History Group meeting on 17 March 2016, Jonathan Tabor (Cambridge Archaeological Unit, CAU) gave a report on excavations at Addenbrooke’s Hospital and particularly the new AstraZeneca site (Cambridge Biomedical Campus). Report by Andrew Roberts, with thanks to Jonathan Tabor and to CAU and AstraZeneca for the photographs. Updated May 2017.

Context

Jonathan Tabor opened his talk by explaining that large-scale developments may have a planning condition which required the developer to commission and fund archaeological work. There have been extensive excavations at the Cambridge Biomedical Campus (CBC) and across the Southern Fringe. Every major development uncovers more archaeological evidence.

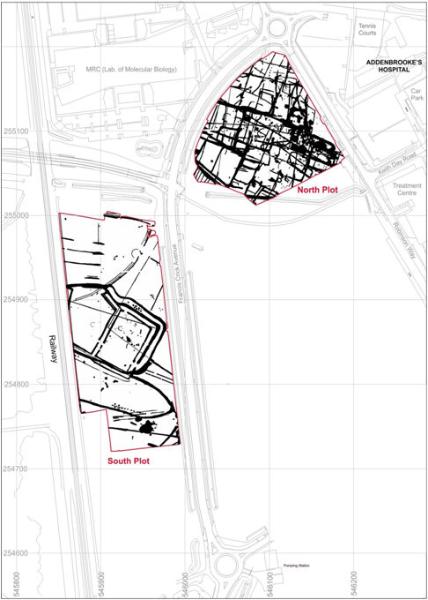

At Trumpington Meadows, there was evidence of Neolithic and Early Bronze Age monuments, an Iron Age settlement and a Saxon settlement, including the bed burial with the cross. At Clay Farm, there were Middle Bronze Age, Iron Age and Roman settlements. At CBC, work in 2002 on the Cancer Research Centre site identified a well-established Early Roman (mainly 1st century) settlement and small cemetery plus 11 pottery kilns. CAU was then commissioned in 2004 to carry out an evaluation of the entire area, which identified a rich archaeological landscape. This included two plots which were now being developed by AstraZeneca, referred to as AstraZeneca North and AstraZeneca South.

Archaeological research

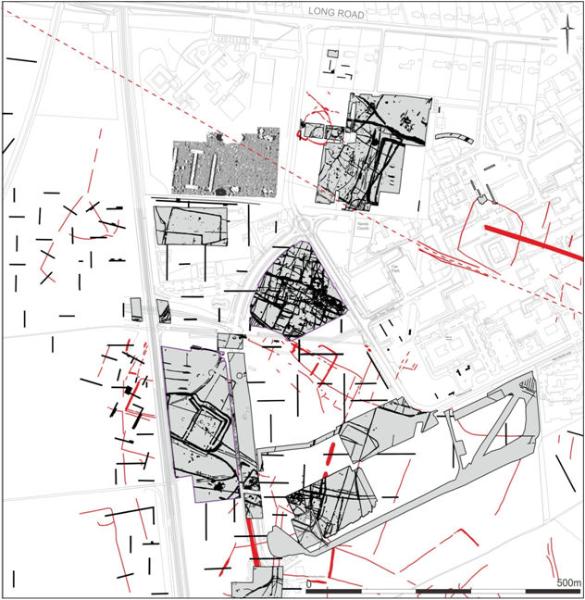

Jonathan said that an analysis of the evidence from crop marks showed a number of hotspots. This was followed by trial trenches and geophysical work which confirmed the crop mark evidence and added further detail. Priority areas identified at that point included a Middle Bronze Age triple ditch enclosure on AstraZeneca South and Early Roman ditches and paddocks on the Papworth site. Beyond the immediate area, crop marks suggested another Early Roman settlement area to the south and an Iron Age or Roman site between the Laboratory of Molecular Biology and Cancer Research Centre buildings. Overall, the area was multi-period with extensive archaeology.

From this point, work progressed on individual development parcels, with the highlights including:

• Laboratory of Molecular Biology: Middle Bronze Age enclosure and Saxon features;

• Energy Centre (south of the Papworth site): Roman Conquest period settlement;

• Francis Crick Avenue: western part of the Conquest period settlement;

• Multi-Storey Car Park (south east of the Papworth site): boundary ditches, evidence of agricultural fields rather than a settlement area, showing how well defined the settlements were;

• Papworth (excavated by Oxford Archaeology East): Bronze Age and Roman field system and part of the Early Roman settlement.

Jonathan said that little was know about the AstraZeneca North site at this stage in the research. When the original hospital was being constructed in the 1960s, construction material was dumped here, adding 3 m of made ground above the original surface. The same chalky marl had been deposited to the east of the site. In the event, there was rich archaeological evidence under the added layer.

Work now began to remove the topsoil on both plots, requiring major work on the north site, with up to 200 lorry movements a day. CAU worked closely with Skanska which was managing the overall project. The excavation took place from July 2014 to March 2015.

AstraZeneca South

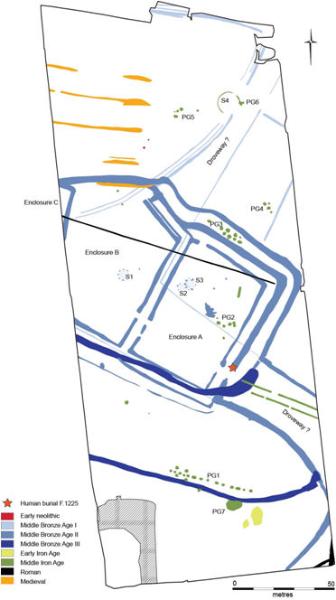

Jonathan said that the area was probably in active use throughout prehistory. The earliest evidence was a Neolithic pit in the north of the site, 3500 BC, including an Early Bronze Age arrowhead. The triple ditched enclosure was Middle Bronze Age, 1500-1100 BC (light blue). There were two drove ways, which seemed to converge on the area, and a field system. There was also Iron Age evidence.

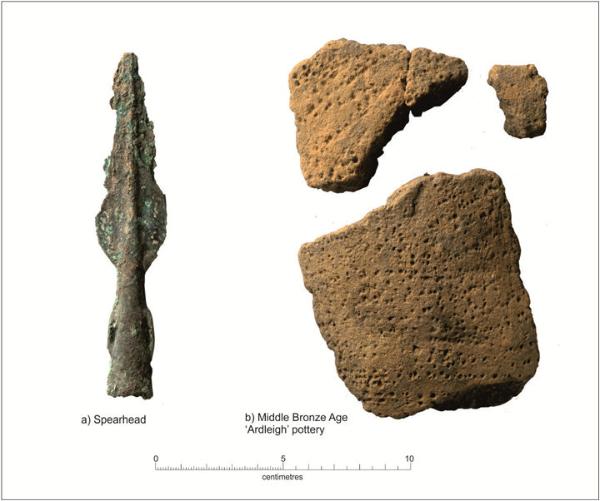

Initially in the Middle Bronze Age there was no settlement, with the area used as agricultural land divided by ditches. Later in the Middle Bronze Age, three large enclosures were developed on an impressive scale (labelled Enclosure A, B, and C in the plan above: the western enclosure C is mainly under the railway line). The enclosures were built over the earlier field system and were probably contemporary with each other, with multiple revisions to the ditches. Jonathan said that the enclosure ditches were rich in charcoal and burnt stone, suggesting there was domestic activity within the enclosure. There was also a large quantity of animal bone, mainly in the ditches, probably from butchering of cattle, etc. Finds included a spearhead, chisel and awl: bronze tools are comparatively rare, so this suggested a site with a reasonable status. In addition, there were around 500 pottery sherds, which were also significant in a Bronze Age context. There was also one human burial (marked with a red star on the plan).

Taken together with Clay Farm, the excavations have revealed an extensive and significant Bronze Age landscape, with enclosures, field systems and similar find assemblages west and east of Hobson’s Brook. Jonathan said that there were a number of enclosures at Clay Farm but none with the same form as those at AstraZeneca. These enclosures were monumental in scale, with a settlement status which was not as grand as the setting. They were possibly at a focal point in the landscape, perhaps a market or meeting space.

Jonathan added that there was also Iron Age evidence on AstraZeneca South, with a round house in the north of the site and clusters of pits within the Middle Bronze Age enclosure, showing that the enclosure was still being reused after 1000 years. There was also an alignment of pits to the south, which may have been reinforcing a boundary, extending to the Papworth site and towards Nine Wells. The largest collection of Iron Age finds came from one of these pits.

AstraZeneca North

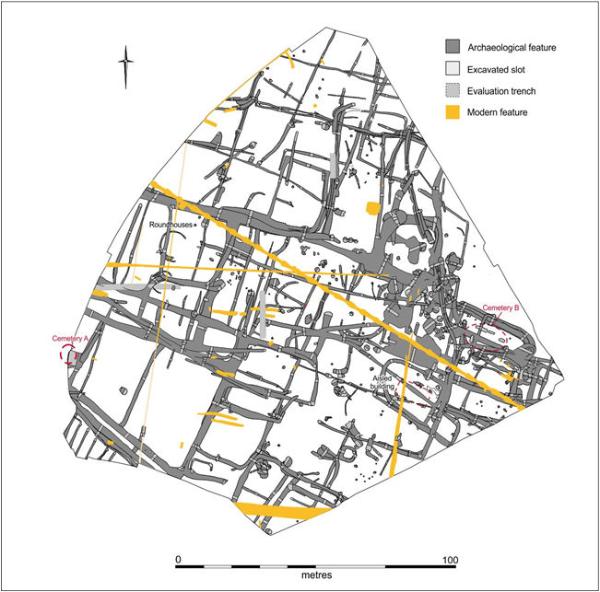

Jonathan continued his talk by describing the work and evidence from AstraZeneca North. Almost all the features were Roman, in marked contrast to AstraZeneca South. There had been some disturbance in the 1960s, leaving ruts in the ground, but the area was remarkably well preserved. It was very wet and muddy during the excavation in the winter of 2014-15.

There were ditches forming settlement enclosures, paddocks and fields, in two main phases, dating to the 1st-4th centuries AD. There were two round houses in the western part of the site, 1st-2nd centuries AD, the foundation trenches of a rectangular structure to the south, and a building to the south east with substantial post holes, possible an aisled building, such as a barn.

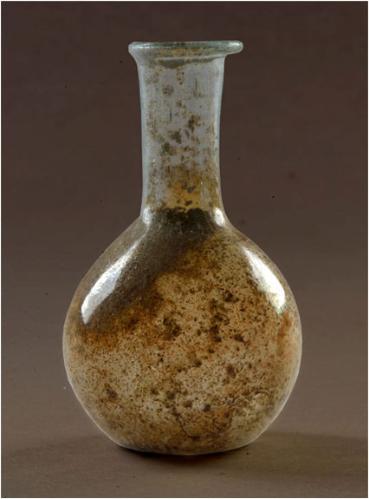

There were two cemeteries: one (Cemetery A) on the western edge of the site, possibly extending under the site boundary, probably contemporary with the round houses, 1st-2nd centuries AD, with burials in shallow pits; the other (Cemetery B) to the east of the area, 3rd-4th centuries AD, with inhumation burials in five graves, two males and three females, two of whom were buried in coffins (which survived as soil stains). One of the burials had a pot and another had a pot and an intact unguent bottle, c. 5 cm high, which was almost certainly imported and had probably held perfume or oil.

There were 12 wells or deep pits on the site, the deepest of which had a wooden ladder. There were also large areas which had been quarried, probably for potting clay or daub. Some of the high status finds were from these areas, probably brought here from elsewhere. There were over 5500 pottery sherds, including the remains of storage jars, etc., largely from local kilns such as Horningsea, plus imported Samian wares and amphora. (Jonathan added that the kilns on the Cancer Research Centre site were probably an earlier date.) There was also 90 kg of animal bone, from butchered cattle; quern stones including Rhineland lava and Millstone grit; 78 Roman coins, mainly 4th century, including examples from Thessalonica and Constantinople; axe head, meat cleaver, etc. The quern stone evidence suggested that crops were being grown nearby while the coins reflect the location of the site near a major route. The overall impression was of a standard rural Roman site used over a long period, with everyday activities taking place in an agricultural landscape.

Jonathan said that the team were still working on the phasing of the site. They thought the earliest evidence was Early Roman, Conquest period, including ditches and a trackway. This was followed by widespread Early Roman ditches, roundhouses, cremations and cultivation trenches (also at Papworth). In the Later Roman, there were regular enclosures and paddocks and the cemetery. By the Saxon period, there was a small settlement within the earthworks of the Roman settlement at the Cancer Research Centre site, whilst an Alfred the Great debased penny was recovered from an infilled ditch at the AstraZeneca site.

Discussion

Jonathan concluded his talk by emphasising the scale of the excavations and the evidence it provided of the prehistory and history of the Cambridge area.

One question was the possible size of the Bronze Age population. Jonathan replied that it could have been an extended family but would have been more sizable when taken together with Clay Farm.

Another question was about Bronze Age evidence from the Wandlebury area to the south. Jonathan said that less work had been carried out on the chalk uplands but the analogous area of the Wessex chalklands was well populated. He added that there was also evidence of rich occupation in the fenland landscape to the north.

Another was about the life-span of the ditches. Jonathan said they were constantly redesigned, particularly in the Roman period.

He was asked whether the large-scale Bronze Age earthworks would have been created by local people or larger teams and replied that they would have required a communal effort.

In response to a question about the coins, Jonathan said that one was silver and another had distinctive features. The Alfred coin was debased, of poor quality silver.

He mentioned that there were probably trackways across the area and the Roman road to the north.

He was asked about the relationship of this area to Cambridge and replied that there was still a debate about the size/extent of Roman Cambridge, with new evidence from excavations at Kettle’s Yard, etc.

He added that after the Saxon period, the Addenbrooke’s landscape reverted to agricultural use, with settlements becoming focused at Trumpington and Cherry Hinton.

Jonathan was thanked for a very enthralling presentation.