Edmund Brookes

November 2019

The story of the railways that came to or will come to Trumpington, based on a talk to the Local History Group on 21 November 2019. This is an updated version of the paper about Railways in Trumpington in 2010. There is also an introductory page about local railways.

1. Introduction

When I spoke about the railways in November 2010, Trumpington had never a permanent railway station. If the Mayor of Cambridgeshire, James Palmer, has his way, we may get one, and I will discuss this later; but you may be surprised to learn that it did have one (albeit temporarily for 1 week) and four pre-grouping (i.e. pre-1923) railway routes did run through or alongside the parish. I will explore the history of these railways and at least one tramway and three garden railways, of which one is extant and one may be recovered, look at the proposed Oxford to Cambridge Railway and finally look at Cambridge South Station. Railways are a keen interest of mine and I know that most of you have only a passing interest in them, so my aim is to interest rather than enthuse you, but there is a lot here of general interest and there are quite a few updates since 2010.

First, I must explain some key dates in British railway history. There are essentially four epochs.

• Pre-1923: Before 1923 the various railways of Great Britain were all independent (after initial amalgamations), with many having running rights over other companies’ tracks (this affected Trumpington’s railways).

• 1923-1948: After the Great War, the railways were in a very parlous state, as they had been under state control and thrashed mercilessly to carry all the cargoes (human and freight) that were necessary between 1914 and 1918 for the Allies to win the war. Totally inadequate compensation from the Government (paltry is a kind word) in no way covered the reparations necessary, the true cost of which exhibited itself in a lack of maintenance and a run down of the assets. The Government brought in a Bill which forced them to combine into 4 big companies. Of these, the London and North Eastern Railway (the LNER) and London Midland and Scottish (the LMSR) served Cambridge and passed through Trumpington. It is slightly ironic that before the Great War, Parliament had obstructed attempts by the companies themselves to combine!

• 1948 – 1994: The nationalisation era. The Big Four railway companies were very run down after again inadequate compensation for the havoc and wear and tear that World War 2 caused to the railways. The Labour Party manifesto of 1945 included a promise to nationalise the railways which they did in 1948. This era saw the demise of the railways as the main form of inland transport with pro-road and anti-rail Transport Ministers such as Ernest Marples. These days he would be said to have a clear conflict of interest as his company (Marples Ridgeway) built quite a lot of our early motorways. After much prevarication, the remaining physical route through Trumpington was eventually electrified, something we take for granted now.

• 1994–2019: The privatisation era (quasi-privatisation is probably a more appropriate word given the actual detailed control which the Department of Transport exerts, even if you do not realise it), which nevertheless has seen very significant investment in our railway infrastructure and passenger rolling stock. Cambridge is one of the very few places where two different companies vie realistically for the London traffic.

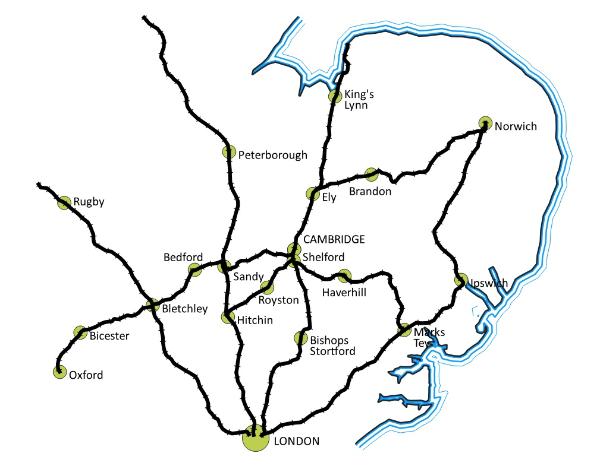

Bacon’s New Survey Map of Northampton, Huntingdon, Cambridge and Bedford (which is pre-1923) shows the eastern boundary of Trumpington as Hills Road up to about Homerton College, when it strikes west to Hobson’s Brook and then north to the River Cam. Trumpington was then part of Chesterton Rural District Council and this is what I mean when I refer to Trumpington in this talk.

I will consider the four railway routes which touched Trumpington and then look at Cambridge Station, finally looking at the prospective Cambridge South Station and the new Oxford to Cambridge Railway.

2. The First and Second Railways

The first two railways (that are effectively the current Great Eastern and Great Northern routes to London) have always been quite closely connected, so they must be taken together initially, but in the very early days this was not so and they were not friends. Please bear in mind that the Stockton & Darlington Railway was only opened in 1825, and the Liverpool & Manchester Railway in 1830. In 1825 there was an epidemic of “ Railway Fever ” and Messrs Rennies made a survey for a line northwards from London, up the Lea Valley and then by the valleys of the Rivers Rib & Quinn and the “towns of” Braughing and Barkway to Cambridge. It stopped there, but was to be extended directly to Lincoln and York in 1827. A map of the time shows it going on from Cambridge to Earith, Peterborough and then Lincoln. In 1835 Mr Joseph Gibbs (a clever and sanguine engineer) projected a different line from London (Whitechapel) to York via Dunmow, Cambridge and Lincoln. The Board of Trade Commissioners did not find favour with this, but preferred a route to York that went via Derby and Rotherham as this would be more remunerative. George Hudson, the manipulative Railway King was still keen to see Cambridge on the main route to the north. There followed a complex battle of intrigue and subterfuge which led to two routes to Cambridge from London.

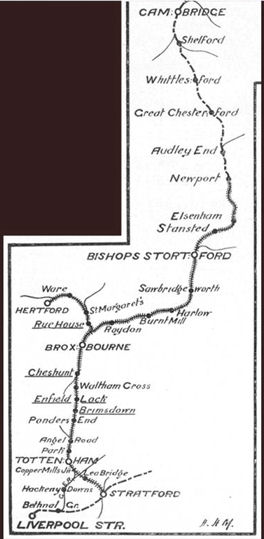

The Northern & Eastern Railway (later The Great Eastern Railway)

As I have noted, the routes from London to Cambridge were relatively early proposals. A report to the promoters of the Northern and Eastern Railway (which we will hear of again) described an examination of three lines from London to the north of England, all involving Cambridge with a branch from south of Cambridge to Norwich (imagine current London to Norwich trains running via Chesterford, Newmarket and Thetford rather than Colchester). A bill was deposited in the 1836 Session of Parliament. The Royal Assent of 4th July that year was for a much truncated Northern and Eastern Railway to be built from London to Cambridge only! The directors though retained ambitions to press onto York which the Act provided for. Various University interests as well as the Corporation of Cambridge were represented on a Committee to support it. The station was probably to be near River Farm in Latham Road and the London terminus in Islington; the route was via Tottenham and Clapton, names which commuters to Liverpool Street will be very familiar with. The Act specified that Cambridge Station should be “ on the south side of the river Cam near a certain farm house called Eddleston Farm in the Parish of Trumpington, and to communicate with the town of Cambridge by a branch road to join the London to Cambridge turnpike road at or near Leys and Cow Common in the parish of Little St Mary, Cambridge .”

Oh that life would be so easy. In 1838, the company applied to change its terminus to the proposed Fenchurch Street station of the London & Blackwall Railway. That partially fell through, and in November 1838 shareholders approved plans to build the London end of the line just from Tottenham to Stratford.

Now, the first railway in East London was the Eastern Counties Railway opened initially from Mile End to Romford in 1839. Its main terminus of Shoreditch (subsequently Bishopsgate Goods Station, the remains of which you still go under approaching Liverpool Street) was reached in 1840. Out in the country it eventually went as far as Ardleigh 4 miles east of Colchester, when funds ran out and it just stopped in open country. Its gauge was 5’, you might think that was odd as the standard gauge nowadays is 4’ 81⁄2” (1435 mm), but there was no requirement then for such a standard.

Parliament sanctioned these changes in 1839, also allowing the abandonment of the line to Islington which had not been started. Money was short, a feature which was to inhibit the Northern & Eastern and its successors for decades, in fact so short that an 1840 Act allowed the abandonment of the Bishops Stortford to Cambridge line. The line now ran just from Tottenham to Bishops Stortford; Bishops Stortford to York is quite a truncation. But then Acts in 1843 and 1844 allowed a continuation to Brandon via Newport. The association with the Eastern Counties Railway developed before opening, such that the Eastern Counties leased the Northern and Eastern from 1 January 1844 for 999 years.

Actual construction proceeded slowly, the track being laid as I noted, to 5’0”. The line was opened from Stratford to Bishops Stortford in stages between 1840 and 1842. Now being built under the aegis of the Eastern Counties Railway, the head of steel pushed north and opened to Cambridge on 30 July 1845. Interestingly as the Eastern Counties had its eyes on coal traffic from the East Midlands and Yorkshire to London, the gauge was changed in mid-1844 to 4’8½” over one weekend before it was opened to Cambridge. Quite a feat. The engineer was the celebrated Robert Stephenson, son of George.

So by mid-1845 a railway built to what is now standard gauge had reached Cambridge from London and indeed opened right through via Ely to Brandon, where it made an end on junction with the Norfolk Railway to Norwich. The so called “direct” line from London to Norwich via Colchester and Ipswich did not open until 1849. Cambridge now had its first railway and we will consider the station and its facilities later.

Given the relatively flat ground that the line passed through, two features must be mentioned. Firstly, though adequate for the time, the curvature (especially between Bishops Stortford and Shelford) and the gradients between Stansted and Great Chesterford, would preclude very fast running, second very few bridges were built for road junctions. Level crossings predominated and were cheap compared with bridges, but they caused their own problems in the future. In the 21st century they present a significant hindrance to both road and rail despite all now being power or automatically operated and controlled from an Integrated Signalling Centre at Romford. To this day, there remain 15 crossing over public roads and numerous others for farmers south of Cambridge. As a comparison on the line from Euston to Birmingham there are no level crossings at all south of Rugby (a stretch of 84 miles).

I have written at length about the building of the first railway both from an interest point of view, and to illustrate some of the difficulties which beset the Northern & Eastern and Eastern Counties Railways. They built our first line without the prospect of the heavy freight traffic, or significant centres of population to generate passenger traffic which other main lines benefited from. This would remain an issue right through to the 20th century where the lines relied on farm generated traffic except for the subsequent coal flow which developed from the north. This meant that capital for developments was always severely restricted.

In the early days, the service from Cambridge to London and through the Parish was not very good and indeed deteriorated after opening, taking nearly 2 hours to London. This was obviously a great improvement on a stagecoach though. The various East Anglian railways came together as the Great Eastern Railway in 1868, and the extension to Liverpool Street Station from Bishopsgate was opened in 1874. From 1870 to 1917 a number of Cambridge Line trains, including through trains from Doncaster and York, worked to London St Pancras. Most through trains which continued north of Cambridge only stopped at a couple of stations between London and Cambridge and some slipped a carriage (i.e. dropped a carriage from the rear of the train without stopping) at Broxbourne for Hertford East, or Audley End. The Liverpool Street line has always suffered from what is one of the slowest routes out of the capital of any main line. Through Bethnal Green, Hackney Downs and Clapton to Coppermill Junction (Walthamstow Marshes) the speed limit rarely exceeds 40 mph until it gets to Tottenham, 6 miles out.

Cambridge Station was built by the Northern & Eastern Railway, but I will deal with its development later.

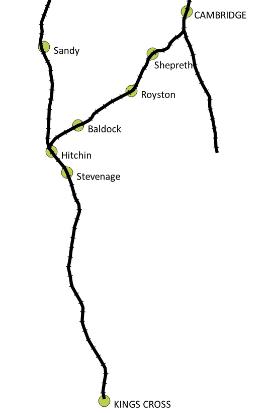

The King’s Cross Route

I have written how the early plans for a London to Cambridge railway were part of a grand design for a direct route to York, and how these metamorphosed initially into a simple line from Shoreditch to Broxbourne, less than 20 miles of the original 188 mile route. We now need to understand how the direct route from London to the north via Peterborough was built, as this is very relevant to the construction of what we now call “The King’s Cross Line” and it is the fifth line in chronological order of arrival at Cambridge.

In the first rush of railway building, the route to York from London was from Euston Station via Rugby, Leicester, Chesterfield, Normanton (bypassing Sheffield) and Church Fenton, and was opened in 1844. That is quite a circuitous route, 35 miles longer than a direct line via Peterborough (though not far removed from the 21st century HS2 route).

The story of the authorisation and building of the direct route to York by the London & York Railway (later the Great Northern Railway) is of a titanic struggle against vested interests. The Great Northern Railway Act received Royal Assent on 26 June 1846, one year after Cambridge had is first railway. The main constituents of the lines approved were a main line from London Maiden Lane (where the new Canal Curve goes off to St Pancras between the tunnels approaching King’s Cross) to York, with a loop line from Peterborough to Doncaster via Spalding, Boston, Sleaford and Lincoln.

The line was built in stages from 1848 to 1852, finishing the main East Coast Route as we know it today. With foresight the Great Northern Railway purchased sufficient land for 4 tracks at the southern end. What a wise decision. While these lines were being constructed a number of feeder lines and branches were authorised, some to be built by the Great Northern and some by other companies, but most ultimately coming into the fold of the Great Northern.

From our perspective, one of these interesting lines was the Royston & Hitchin whose act was passed on 16 July 1846. This line was initially projected in 1845 as the Cambridge & Oxford Railway, 73 miles in length from a junction with the Eastern Counties Railway at Cambridge through Royston, Hitchin, Luton, Dunstable and Aylesbury to Oxford. Oh that it had been built as such, but on finally getting the Royal Assent it was pared down to a line from Hitchin to Royston, 13 miles in length and double track. After some discourse with the Cambridge based directors who had hoped to get it extended to Cambridge, the company was leased to the Great Northern Railway who were then building their main line. The Royston and Hitchin Railway was opened on 21st October 1850, the same year that the Great Northern main line to London opened. A further Act allowed the Great Northern as lessees to build a line from Royston to Shepreth, there to meet the proposed Cambridge to Bedford branch of the Eastern Counties Railway (it gets more complicated!). This line actually ended about 100 yards east of the current Shepreth station, and was opened in 1851. Coaches completed the journey to Cambridge. The Cambridge and Shepreth Junction Railway Bill (to complete the line) was introduced by the Great Northern in 1850 for a line from a junction near the Botanic Garden with a spur to the Eastern Counties mainline, with a station near Silver Street. Though supported by citizens of Cambridge, the University strongly opposed it, largely because it would be inconvenient to have two stations in Cambridge. The bill was re-introduced in 1851 but not proceeded with, as the Great Northern was proposing its own extension from Shepreth. Not surprisingly both the City and University opposed it.

The story now gets even more complicated. The Eastern Counties Railway then took over the lease of the Royston & Hitchin Railway for 14 years and extended it from just east of Shepreth station to Shepreth Branch Junction, Shelford, as a single track, hence the name if you ever wondered why it is called Shepreth Branch Junction. There to join the main London line. This was the only portion of the Eastern Counties’ approved line from Oxford to Cambridge that was ever built, opening in 1852. The Eastern Counties and the Great Northern then decided to be friends and from 1st April 1852 competition to Cambridge ceased. The Eastern Counties ran trains from Cambridge right through to Hitchin and were due to hand the line back to the Great Northern. However, the Great Northern sought powers to build their own line from Shepreth to Cambridge via Barrington and Haslingfield to join the Bedford & Cambridge Railway (then being built) with running power 3 miles west of Cambridge, but then to have their own station close to Christ’s Pieces. Eventually common sense prevailed and an agreement of 1864, confirmed by Act of Parliament, effectively granted the Great Northern running powers over the Great Eastern Shepreth branch, which the Great Eastern promised to double as it had been built as a single track. By 1866 they had not doubled the track owing to their [perennial] shortage of money but did so the next year.

So came into being the fifth line into Cambridge, but doubtless then the second in importance and now the first.

By 1868 the pattern of services on the main line south was established with trains to both London Liverpool Street and King’s Cross. King’s Cross trains usually started and terminated in Platform 2 at Cambridge Station, as working through to Kings Lynn only started with electrification. The reason for this change of the main London terminus from Liverpool Street to King’s Cross a few years ago was firstly that it was quicker (despite being longer) with better Underground connections, and to relieve pressure on the line down the Lea Valley as Stansted Airport traffic assumed greater importance. When I have been travelling or commuting, the presence of two high quality routes to London has meant that I have only once even failed to get to London.

That then is the story of how the current railway along the eastern boundary of the present Parish arrived.

3. The Third Railway: the London and North Western Railway (the Bedford Line)

What ultimately became part of the London & North Western Railway which in the 19th century was not only the most powerful railway in the land, but also one of the largest Joint Stock Companies in the world, started off as a small private railway called the Sandy & Potton!

This was promoted privately by Captain Sir William Peel, and opened to freight on 23 June 1857 and passengers in April 1858. Why Sandy? Well the London & York Railway through Sandy had been opened in 1850 and Capt Peel owned the land from which he wanted to transport goods. He had won the VC at the age of 32 and earned the rank of Captain in the Royal Navy. The locomotive was named Shannon after one of his ships and finally moved to the Wantage tramway, it is now at Didcot railway Centre. Sadly he actually died aged 33 in the same month that the Sandy & Potton Railway was opened.

The Act of Parliament for the Bedford & Cambridge Railway (incorporating the Sandy & Potton Railway, whose original locomotive was on display in Wantage) allowed for a separate station in Cambridge, roughly where Pordages warehouse used to be and in what became the London and North Western goods yard. However by the time it came to build the station, relations with the Eastern Counties had improved and it was agreed to make a small contribution to the enlarged Cambridge Station then being rebuilt by the Eastern Counties.

The Bedford & Cambridge Railway began passenger services to Cambridge on 7 July 1862 and was absorbed by the London & North Western in 1865. The London & North Western and the Great Northern then enjoyed very cordial relations. It was this friendship which enabled the Great Northern to put very heavy pressure on the Eastern Counties Railway to give it access to Cambridge over the Shepreth Branch line referred to earlier. At one time the Great Northern contemplated its own line from Shepreth through Haslingfield to join the Bedford and Cambridge about 3 miles west of Cambridge at Lords Bridge, and then to its own terminus near Christ’s Pieces.

The railway was always bridged by Long Road whereas the Eastern Counties to London had a level crossing. Reference has often been made to a Coprolite Siding and it did exist, but its site remains a mystery. Railway Magazine of January 1918 quotes “ Readers will be interested to know that a 0-6-0 tank carrying the name “Easingwold” is at present working on some coprolite excavations near Grantchester, Cambridge. This line joins the London North Western line between Cambridge and Lord’s Bridge ”. There was also a siding on the site of the Cambridge University Press roughly adjacent to the London North Western Goods Shed. Given the size of Trumpington in the mid-19th Century the line swept in a long left hand curve up from the Cam valley to clear the village and head to what is now Hills Road bridge. You can see the track bed today at the M11 and River Cam bridges of course, but it is obliterated across Trumpington Meadows and along the Guided Busway.

The London & North Western used the Bedford and Cambridge line to take traffic to feed into its long distance services which then stopped at Bletchley (long before Milton Keynes was even thought about) and the line settled down to a steady existence, usually being operated in two sections east and west of Bletchley, with a couple of trains through to and from Oxford where it had its own station in what is now the car park of the current one.

I will look at the new proposals for an Oxford and Cambridge Railway later.

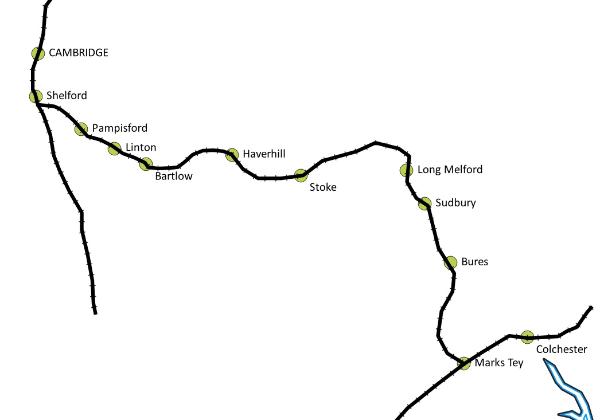

4. The Fourth Route, to Colchester

The Haverhill line, which branched off just south of Shelford station, was started from Marks Tey in 1846 but not opened right through until 1865. It closed in 1967, and while essentially a rural cross-country route did on summer Saturdays carry some through trains from the Midlands to Clacton. The line was famous for only one thing, the locomotives which hauled most passenger trains were the last 2-4-0 tender locos in the country, Class E4, of which the last is now in the National Railway Museum.

5. Twentieth Century and Later Consolidation

Until the 1980s, it was always considered that the Great Eastern was the mainline, albeit that it was built cheaply, going round hills (especially between Newport and Elsenham) and using level crossings, whereas the Great Northern was built much straighter at greater capital cost

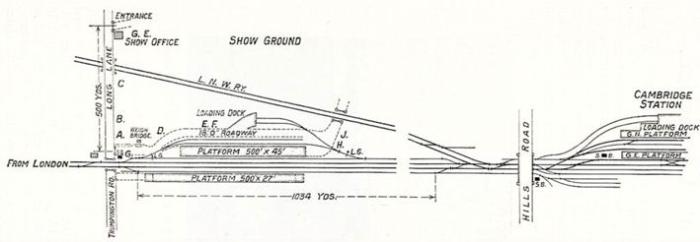

As the railways matured and the Industrial Revolution continued there were improvements to the basic infrastructure (though the Bedford line was fairly immune to these). Proper signalling was installed, refuge sidings and then goods loops were built to allow the many freight trains (including bricks and coal for the capital), which were effectively unbraked, to be passed by passenger trains. An up goods line was provided in 1922 to Trumpington (Long Road) from Cambridge where a signal box was installed to divide the section to Shepreth Branch Junction. Hitherto there had only been a Crossing Keeper’s hut. By the way, for those of you unfamiliar with the terminology, in railway parlance an “up” line is one generally carrying trains going towards London, and a “down” line away from the capital. A similar down loop (known as The Cupboard) was completed at the same time for the 1922 Royal Show. Eventually the Long Road (London & North Western) Bridge was rebuilt and the level crossing for the London line was replaced by a similar style bridge which had (and still has) space for 4 running lines.

Train services settled down and slowly developed. Bradshaw of 1910 shows 24 trains to and from Liverpool Street or St Pancras with 2 extended to York and several to Norwich, quite apart from King’s Lynn and Hunstanton trains. Splitting and joining at Ely was common. There were only 6 trains on a Sunday. The first arrival in London was not until 08:57 and that took over two hours! The 1922 service was broadly similar.

You need a magnifying glass to read Bradshaw but in 1910 there were 13 trains from Cambridge to and from Hitchin, only 5 of which stopped at all stations. The first arrival into King’s Cross was not until 09:34 by changing at Hitchin!

On the London & North Western, Bradshaw of 1910 shows 6 daily Bedford-Cambridge services with, 1 on Sundays, with 6 and 2 respectively in the return direction. Three of the weekday services ran to or from Oxford. In 1922 it was virtually the same, but with 2 in both directions on Sunday.

While we may moan the loss of the Bedford service, the current London service is by far the best we have ever enjoyed, even if the rolling stock is not so comfortable as 20 years ago.

6. The 1922 Royal Show

Many people remember the Royal Shows of 1951, 1959 and 1960 held on what is now known as the Clay Farm site, but there were no special rail facilities, and any traffic was handled at Cambridge Station. However, the 1922 Royal Show took place on a site between Long Road, Trumpington Road and Hobson’s Brook and warranted a special station built from railway sleepers with 3 platforms (one for goods traffic). The station was built by the Great Eastern essentially in the gap between the London and Bedford railway lines to handle machinery, livestock and passengers in very large numbers. The main platforms were built alongside what became the up and down loop lines which were extensions of extant short reversing sidings or headshunts underneath Hills Road Bridge adjacent to Cambridge South Signalbox. The third platform was effectively a siding with a platform face and is shown in the photographs. Any London & North Western traffic was handled at its own goods station or handed over to the Great Eastern. Some limited traffic was handled at the main station.

This was all installed for a few days use and then mostly stripped out. The use of the facilities was planned like a military operation and the staff provided to suit. Few trains were stabled on site and trains came from all over the country. Southbound passenger trains were sent on to Park Station (now known as Northumberland Park where the Victoria Line depot is), for servicing and turning round, northbound trains sent to Whittlesea or Norwich. 25 livestock trains alone were scheduled to arrive in a period of 21 hours quite apart from long distance passenger trains from as far as Manchester (via Lincoln) as a day trip. Special trains were provided locally to visit and return from the site. Such an operation would take several years to action these days and all this was done without the aid of any computers, etc! There is a full report in The Railway Magazine of that year. See photographs in the report on the 2010 meeting.

7. The Effects of the Grouping, 1923

After the first amalgamations to form railways such as the Great Eastern and London & North Western, schemes to seriously amalgamate railways did not start to gestate until towards the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries. One involved the Great Eastern and Great Northern with the Great Central Railway. Despite obvious advantages, Parliament did not look favourably on these and until the London and North Western and the Lancashire and Yorkshire amalgamation of 1922 none came to fruition. As noted earlier, the 1923 amalgamations were forced on the railways by Parliament which also looked even then at nationalisation. So far as Cambridge was concerned, the Great Eastern and Great Northern combined, which meant the small Great Northern engine shed could be closed but there were few other manifestations. The London North Western Goods yard at the corner of Brooklands Avenue and Hills Road remained (where Pordages subsequently had their depot).

The King’s Cross services remained distinct, often being hauled by large express engines being run-in from King’s Cross after overhaul, including the famous Cambridge Buffet Car Expresses (also known as Beer Trains to generations of Cambridge students) which were very successfully introduced on a 2 hourly basis. The Royal Train continued to run from Wolferton (for Sandringham) to and from King’s Cross to avoid unnecessary procedures when the Monarch entered the City of London at Temple Bar.

World War 2 brought further strains to the railway system with the vast quantities of materials being brought to build the many airfields in East Anglia. The land between the London and Bedford lines north of Long Road was completely filled with an additional second down loop (which I saw used only once) and a series of sidings for wagon sorting and storage. This was effectively started after the 1922 Royal Show. After World War 2, the usage dropped and by the early 1960s they were effectively out of use, except that I once saw them full of old 16 ton mineral wagons.

To increase line capacity, what were called Intermediate Block Signals, worked automatically, were installed between signal boxes. One was installed in each direction between Trumpington and Shepreth Branch Junction as this line was even then very heavily trafficked with trains for both London termini, not forgetting the Haverhill line.

8. Nationalisation and Rationalisation

World War 2 had the same effect on the railway system as World War 1. During the War, the railways were run by a Railway Executive directed by the Government, and they were only really returned to full private operation as the railways’ nationalisation loomed. Taking effect from 1 January 1948, there were little obvious changes to the Trumpington lines except for reliverying – Eastern Region green and London Midland crimson red. However the rationalisation of transport facilities (not all of which can be blamed on Dr Beeching!) inevitably lead to changes.

Dieselisation meant that the weekly Sunday train of dead locos from Stratford to Doncaster which I remember (when we got home from Church) were no more. The Haverhill/Colchester line shut and the ubiquitous Class E4 2-4-0 tender locos which dated back to the Great Eastern days were withdrawn. Surprisingly, freight facilities on the Bedford line went before passengers in 1966 and then passengers in 1968. I have a slide taken from the Church tower of a Bedford train ploughing its lonely way across the PBI land, now Trumpington Meadows. Surprisingly, in 1955 the Oxford-Cambridge line had been identified for development as part of an outer London ring for freight traffic. While flyovers were built at Bletchley and rebuilt at Sandy, it was all wasted.

The rundown continued with local freight services being withdrawn south of Cambridge. The nadir was probably reached in the early 1980s despite a healthy development of long distance London commuter traffic. At long last, investment in electrification then recommenced. The Liverpool Street-Bishop Stortford scheme of 1958 had enticingly continued about 1 mile north of Bishops Stortford. In 1968 the Cambridge main line down the Lea Valley had been electrified from Cheshunt to Clapton/Hackney, but further work was piecemeal. The King’s Cross to Royston line was electrified in 1976 with an hourly diesel multiple unit shuttle to Cambridge. Bishops Stortford to Cambridge was completed in 1988 followed by Royston to Cambridge and Cambridge to King’s Lynn in 1990. The latter coincided with the abolition of Trumpington Signal Box and the opening of the large signalling centre at Cambridge which controlled all the lines from Stansted to near March. Nowadays Romford Integrated Signalling Centre controls all the signals.

9. The Tramway

The Coprolite mine in Trumpington is a separate story. A tramway was used in the pits on what is now Trumpington Meadows and this then ran up a ramp to a loading bank beside the A10. Long disused, the bank was removed in the 1960’s leaving the concrete bund free standing. This was demolished/blown up by the Engineer Wing of the University OTC in early 1970, an exercise which nearly went badly wrong and a friend of mine was quite seriously injured in the incident. Nothing now remains. These photographs show several aspects of the mine, the large machine for stripping the overburden and the steam shovels for extracting the coprolite into basic hopper wagons on the horse drawn tramway. As noted earlier, at one time there was a siding off the Bedford Line, but its location is not known.

10. Garden Railways

I am aware of three garden or miniature railways (one of which is extant and one may be being rebuilt). As they are on private property, I will not reveal any other details, except to show a picture of the 7¼” passenger carrying Trumpington Miniature Railway.

11. Cambridge Station

Cambridge Station had a single platform when it was first built. This was nothing strange in the 19th century, especially if the town they served was largely to one side of the railway, as Cambridge was then. Over time, most became 2 platforms with a couple of notable exceptions. Of those that are left, Dunbar station is having its second platform restored but Malton is not.

The single platform has probably survived because it was very long and can hold one 10 car and one 12 car train simultaneously. The London & North Eastern installed power signalling as long ago as the 1920s which meant the ubiquitous double crossover right by the entrance to the platforms was not an operational hindrance, despite its 15 mph speed restriction, especially with the 4 bay platforms.

But it was not always so. Within a few years of opening (in 1848) the station was provided with a wooden island platform accessed via a steep footbridge roughly where Platforms 7 & 8 now stand. A further remodelling in1863 saw the platform removed, and while there were plans in 1886 to build a new double platform. Nothing became of them until this decade. One wonders how Cambridge Station would operate now without Platforms 7 and 8 which can each take a 12 coach train.

12. Current Status, late 2019

Nowadays there are regular but infrequent block freight train services through Trumpington. Stone trains to Harlow, Hoddesdon and, Freightliner/ Intermodal trains from London to the Midlands and north, but no pick-up services. Some container trains from London to Felixstowe pass and then travel via Newmarket if there are capacity constraints via Chelmsford. This avoids the bottleneck around Stratford and is one reason why the Rail Freight Group want access to Cross Rail for intermodal trains! Also if the Great Northern Main line is blocked between Hitchin and Peterborough, trains can be diverted via Cambridge (with suitable pilots). If there are engineering works, Hull Trains regularly come to and terminate at Cambridge, passengers then transferring to the Great Northern Railway. Given both were owned by the same company, it is probably not surprising!

Though the Up Goods loop to Trumpington Box was lifted years ago, the Down Goods Loop has now been signalled for passenger trains to ease congestion south of the Station. It is possible for a train to run into Platform 1 from the south and be stationary ahead of a train in front which has run slowly into Platforms 2 or 3!

However the passenger service has been transformed from what was a 2 hourly train to Liverpool Street with a Buffet Car Express in the intervening hour to King’s Cross, supported by bi-hourly stopping services operated by 1st Generation Diesel Multiple Units (DMUs). Cambridge now has 2 express, 3 semi-fast and 2 stopping trains an hour, all to London, coupled with a half hourly 2nd Generation DMU train from Birmingham or Norwich to Stansted Airport. That makes 9 trains each way each hour off peak on the lines through Trumpington. Obviously the Bedford Line is no more and cannot be replaced because of the Guided Busway and other obstructions further west, including the University Radio Astronomy telescope at Lords Bridge.

Both of the new bridges over the railway (the Guided Busway and Addenbrooke’s Road bridges) allow for a third and fourth rail track.

To bring it right up to date, in 2019 because of capacity issues south of Broxbourne/Cheshunt, Network Rail has just reinstated a third track from south of Brimsdown to Tottenham on the Liverpool Street Line (and just approved a fourth) to give space for more trains to Stratford for Docklands, as Stansted Airport traffic takes up so much capacity on the existing pair of tracks. This has been built on what was a goods line for coal trains built back in the 1900s but taken up 50 years ago. Perhaps there is a lesson for Cambridge South Station.

13. The Oxford-Cambridge Railway and Cambridge South Station

The Current Situation (late 2019)

With the publication of outline proposals for the new route between Bedford and Cambridge, I will start by reviewing the current status of the whole infrastructure:

• From Oxford to Bicester there is an upgraded twin track line in use by Chiltern Rail with a frequent Marylebone service competing with the Great Western Railway to Paddington.

• From Bicester to Bletchley there is a double track out of use with a flyover over the West Coast Main Line at Bletchley. This gives access to both the main line to Milton Keynes, and to the Bedford Line at Fenny Stratford. The track bed has been allowed to get thoroughly overgrown by trees and vegetation and a bulldozer would not get through, what a shame. The track will need to be completely rebuilt and will give a service from Oxford to Milton Keynes Central as well. There is also a link to the old Aylesbury line extant at Calvert giving further route options to Milton Keynes and which are factored in.

• From Bletchley to Bedford the original double track route carries an hourly but very basic passenger train (currently operated by old District Line D78 stock which has been completely refurbished). At the Bedford end, Bedford St John’s station was closed and a single line west to north curve built to take trains into Bedford (Midland) station. The line suffers from a lot of level crossings and if express trains operate, they will have to fit the local ones in. It is also a useful connection between the West Coast and Midland Main Lines.

• From Bedford to Sandy there was originally a single track line with one passing place. Most of the trackbed remains but is built on approaching Sandy and the flyover across the East Coast mainline was removed some years ago.

• From Sandy to Cambridge the double line trackbed is built on through Potton and Gamlingay, by the Mullard Radio Telescope and the Guided Busway, but reasonably extant though open country, even if incorporated into fields.

The challenge

It will be reasonably easy to restore the line from Bicester to Bedford and subject to a Transport & Works Order being granted, work will start with the objective of phasing in services from Aylesbury and Oxford to Milton Keynes and Bedford respectively from 2023.

The major challenge is building what will effectively be a new line from Bedford to Cambridge if there is the political will to commit the necessary resources. This is not going to start, assuming the will is there, for some time. The so called routes published show a variety of lines from either Bedford or west of Bedford to Cambridge over a wide sweep of countryside through or near to either Sandy or St Neots entering Cambridge from either north or south. That gives plenty of options for the various interested and opposing groups to argue over. Giving a personal opinion, a southern entry to Cambridge is the more likely, involving joining the current Royston line somewhere east of Shepreth and then passing a new Cambridge South station somewhere at the Cambridge Biomedical Campus.

This will require an upgrade of the Royston line which already carries 5 trains an hour in each direction off peak, and a major rebuild of the line from Shepreth Branch Junction to Cambridge which carries 9 trains each way. In my view that is essential. It is fortunate that Long Road Bridge was built to take 4 tracks, as do the two new bridges, as I consider 4 track essential whatever Mayor Palmer may say. The recently re-opened Borders Railway from Melrose to Edinburgh was built with insufficient infrastructure for effective operation. Lengths of double track to allow efficient passing of trains at speed were cut back to save money and this has resulted in unnecessary delays to trains.

14. Cambridge South Station

I will conclude by addressing the issue of the proposed Cambridge South Station, and this also links in to the new railway from Oxford. First it has to be decided what the passenger market is, is it local traffic from north and south to Addenbrooke’s Hospital and Cambridge Biomedical Centre, or is it long distance access to the same (which could also be achieved by efficient, regular and reliable connections between express and stopping trains at Cambridge Station)? Whichever is decided, if it is built with just two lines of rails, my view is that it will be impossible to operate efficiently without significant delays to existing trains if just one runs late, and that is bound to happen. At a minimum, it needs 4 tracks from Shepreth Branch Junction to Cambridge, with the points there upgraded to 50 mph for trains heading to/from Royston rather than the current 30 mph limit. If the new Oxford to Cambridge Railway comes in via Shepreth, I would urge a flying junction (i.e. overbridge to take King’s Cross bound trains over/under ones to/from Liverpool Street avoiding conflicting movements, as well as all lines being built for bi-directional running. Because of the tight space, the flyover could be built north of the junction, and not adjacent to it.

References

History of the Great Northern Railway, Charles H. Grinling, 1898, George Allen & Unwin.

London to Cambridge by Train 1845-1938, Reginald B. Fellows, 1976, The Oleander Press.

Oxford to Cambridge Railway, Vol Two, Bill Simpson, 1983, OPC.

The Cambridge Line , Michael R. Bonavia, 1995, Ian Allen.

Great Eastern Railway, Cecil J. Allen, 1955, Ian Allan.

The Railway Magazine – various volumes.