Philippa Slatter

Eva Hartree (1873-1947) was a Cambridge Borough Councillor from 1921-27 and 1929-43 and the first woman Mayor of Cambridge in 1924-25. This paper is based on a talk given by Philippa Slatter at the meeting about Two Trumpington Mayors, September 2019. See also the outline of Eva Hartree’s life.

One of the areas of local history research that I think this group should be most proud of is our determination to have the new extensions of Trumpington village given place names rooted in the history of our area, and which pay tribute to the people who lived here before us. If you have explored the new streets close to the Clay Farm Centre, you may have seen the ‘Hartree Lane’ street name and if you have visited the Centre, you may have seen that the main hall is named the ‘Eva Hartree Hall’. This paper will go some way towards explaining how those names got there.

On the 12th of August 1925, about two thousand citizens of Cambridge held an open air meeting on Parkers Piece. They had turned out because of a recent proposal which had been made by the Cambridge Town Council. Following some angry speeches, the crowd passed a resolution of protest, and were so fired up that over half of them decided to take a written version of their resolution to the Mayor that very evening. They marched out of the town centre, down Trumpington Road, along Newton Road to the home of the Mayor at Number 21. They pulled along with them a four-wheeled wagon still containing the speakers who had used it to address the crowd.

The issue in question was the creation of a parking place for motor vehicles in Drummer Street, on part of Christ’s Pieces. As today, citizens of Cambridge passionately resisted any encroachment on the sacred turf of our various open spaces, but the Mayor held firm. She pointed out, with great foresight, that motorcar ownership was within the reach of ordinary citizens, and the need for proper parking places for motor coaches and motor cars was increasing. Following this encounter, she chaired a special meeting of the Council called to discuss the issue, the plan was confirmed, and in due course the only complaint on this subject was that there were not enough parking spaces!

The Mayor in question was Councillor Eva Hartree, the first woman Mayor of Cambridge, who had been elected to the Council to represent Trumpington in1921. I had no idea that a car parking dispute would be one of the dramatic events of her mayoral year and indeed how many other aspects of her life would resonate with me.

So, who was this woman, how did she come to be living at 21 Newton Road, and what can we learn about her life from the available records she has left behind?

My starting point came in an envelope from Andrew Roberts which contained two photocopied articles from local newspapers. One was an obituary notice written in 1947 which can be summarised in its titles ‘Death of Cambridge’s First Woman Mayor, Mrs Hartree’s Long Public Service, 20 Years a Member of the Town Council’. The other, written in 1930, was one of a series called ‘Pen Pictures of Women Workers’, while she was still very actively involved in civic life. It is more conversational, almost fanciful, as I will illustrate with a quote which is a more flowery version of my own research question – what made her the woman she became and prepared her for the life she lead?

” Councillor Mrs Hartree was born at Stockport one Christmas Eve. There was present .. a fairy of a public spirited turn of mind, who … popped in a gift for public service – a gift the recipient was destined to develop very early in life. “

The article provides an outline of her life up to 1930, and it becomes clear that what the Cambridge journalist called a ‘public spirited turn of mind’ probably owed much to Eva’s father, Dr Edwin Rayner.

He was one of the leading medical men in the Manchester area, having studied at Owen’s College, at London University, and in Paris where his uncle was in practice. Among Edwin Rayner’s duties as the certifying surgeon to many local factories was interviewing young workers, and he pursued many concerns regarding their safety during long hours in operating machinery. Certainly he will have been a significant influence on the education that his daughter was given and the social concerns she pursued all her life.

At this point I must admit to a little personal bias. I myself come from a suburb of Manchester, and went to school in that city. My school was under the historic influence of many of the big names in political and social reform movements, particularly concerned with the education of women. These were the Manchester social circles that Dr Rayner and his daughter would have been familiar with, and they had many links to Cambridge where she was to live most of her adult life.

Thanks to the newspaper record, we know that Eva Hartree went to Girton College Cambridge, which is excellent news for any local history research as I discovered when I went to consult the college archives with the help of their archivist and librarian.

Here I was shown the letters written at the time of Eva’s admission to the College to read for the Natural Sciences Tripos, which was a powerful link to the people involved.

One was the letter from Eva’s mother to the Executive Committee of the college. She wrote formally, in the third person, “Mrs Rayner will be obliged if the Executive Committee of Girton College will allow her daughter Eva Rayner whose certificate of character is enclosed, to commence residence at the Easter term 1892. She has recently been through the Entrance examination held at Burlington House.” The file duly contains the letter from her school in Hendon affirming her to be of good character. A fascinating aside is supplied by the letter in the centre, in which Mrs Rayner, writing in the first person with minimal punctuation says “perhaps some other form of writing would be more acceptable, if so, you would let me know how to word it I shall be obliged not having seen anything of the kind I scarcely know how to compose it”. Reading this, I wonder if even educated middle class women of Mrs Rayner’s generation depended more on being schooled in accepted written etiquette, and were a little at a loss when breaking new ground. Her daughter, armed with a Cambridge college education, would certainly not be at such a loss.

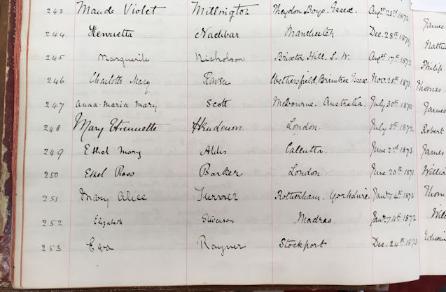

Also in the Girton archive is the register Eva signed when she entered the college. This Register covers the years from 1884 to 1965 and makes fascinating reading. The entry of her name gives us details of Eva’s schooling. In her case, this was firstly at home, followed by schools in Liverpool and London, then with families in Paris and Hanover. It is interesting to look at the background of her contemporaries. In the column headed ‘father’s calling‘, doctors, clergy, merchants and farmers are in the majority, although some are simply described as gentlemen, and it could be that ‘merchant’ was a convenient name for a variety of middle class trades.

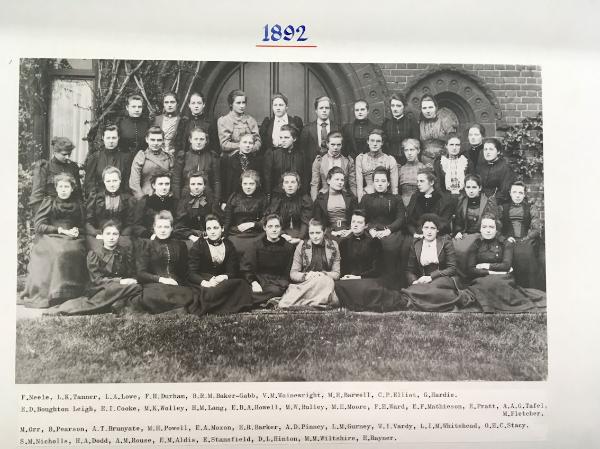

Another treasure in the archive is the Girton College album of First Year photographs 1892- 1915, including the class of 1892 on the first page. Eva is on the far right of the front row, looking very determined, if a little anxious. The young ladies joining Eva in the study rooms of Girton and the lecture halls of Cambridge in 1892, were very similar to her in socio-economic background and education, but they were entering a world of tumultuous change.

Another resource pointed out by the archivist was the Girton Review , and, knowing the considerable achievements of Eva Hartree’s later life, I was sure that I would find evidence here of interests and talents to come. I spent some time scouring the pages of the Review for the years when she was a student but I found no reference to Eva Rayner. She did not feature in the lists of committee members for sports, hobbies or academic societies, or in the accounts of their meetings. She did not make any contributions to the poems or articles featured in the Review, or achieve any sort of honours that I could find. It is of course a characteristic of local history research that we can spend a lot of time proving that something is not true. I did, however, find a wonderful obituary written by E.W. Parsons in the Review for 1947.

In the summer of 1895, after three years of study, Eva Rayner successfully completed her Natural Sciences tripos second class. She was of course banned from taking part in the degree ceremony to receive it formally from the University as Cambridge did not at that time award degrees to women. Soon afterwards, in August 1895, she married a young man called William Hartree. Who was this young man and how did they meet?

There is a record for William Hartree in the People in Trumpington section of the website. William Hartree was born in London in 1870, so was three years older than Eva. The record lists when and where he lived in Trumpington. It gives details of his profession at the time of the census, but it does not record how he met his wife. However, if we look again at the Girton notes we see that Eva’s mother’s maiden name was Hartree, so it is safe to speculate that he was a cousin of some sort, and this is reinforced by the note for 1911, when Eva Hartree was recorded in the census as staying in Middlesex with her brother Edwin Hartree Rayner.

What do we know of Eva’s early married life in Cambridge? The 1901 census record shows that the young couple were living in Cranmer Road, Newnham, and at least two of their four sons had been born. William Hartree was working as a lecturer and demonstrator at the engineering laboratory of the university. They were in due course to have five children, four sons and one daughter, but all but one died in childhood. Only their son Douglas survived, and he went on to have a distinguished university career in Manchester and Cambridge.

The 1930 newspaper article has an account of Eva’s early married life. From 1895 to 1913, she was not a particularly public figure, but very active in organising various activities of the local Red Cross, as might be expected of a doctor’s daughter in these years before the First World War. We have to look elsewhere to discover what other influences were developing the future town councillor.

We do not know what contacts Eva had with the town of Cambridge during her years as an undergraduate. It could be that the life of this Girton student was so sheltered and constrained that she saw little on her way to and from the lectures and seminars that were held at the university buildings. It could be that she did not notice the dreadful slums of Castle Hill that she passed through.

We do not know much about her life as a young wife and mother, when she was living in Cambridge, but it is unlikely that the daughter of Edwin Rayner, who had accompanied him on his visits to the factories of Stockport, and heard his concerns about the health and safety of their workers was unaware of or uninterested in the world about her. It is far more likely that she soon became involved with the people that local historian Antony Carpen has called ‘The Women Who Made Modern Cambridge’, and whose stories he is so enthusiastically uncovering.

We had a talk in 2018 about the patient work of Millicent Fawcett, and it was during these years that many women in Cambridge were working behind the scenes in the committees that provided housing, healthcare and recreation for the poor.

In 1886 Eleanor Sidgewick (nee Balfour) started the Cambridge Ladies Discussion Group which was far from the teatime talking shop its name suggests. It contained a redoubtable group of well- educated, well connected women who meant business. For example, in 1884 Ellice Hopkins had published her book “Work among the Working Men” and used it as evidence to raise money to build the Working Mens Club on Mill Road. This building at last gave men an alternative to the public houses which otherwise absorbed their time and money. Trumpington Village Hall originated in a very similar way in 1908.

As well as the practical help provided by many voluntary organisations, these women and their successors carried out painstaking research in a variety of areas that concerned them. In 1906, Eglantyne Jebb wrote “A brief study of social questions” This book contained contributions by many women, including Eva Hartree. Gwen Raverat, the talented artist whose etchings will be well known to some of you, carefully crafted a street map to illustrate the distribution of poverty in the town. In 1909, Eleanor Sidgewick started a Cambridge branch of the British Federation of University Women, an organisation which was a natural development of the earlier discussion group.

Although not yet elected as councillors, many Cambridge women were serving on Council committees and developing the practical political skills required. Although women could not yet vote, they were not banned from standing for election to local councils. There were two women candidates in Cambridge elections in 1908, and finally the splendid Ada Keynes was elected in 1914.

In 1913, the Hartree family moved away from Cambridge, first to Farnham in Surrey, where Eva became honorary secretary of the Suffrage Society. While there, their son John died, aged 6. They then moved briefly to Falmouth, where Eva worked with the newly formed women’s police force and the local Girls’ Club. In 1915 they moved to Guildford and although they were only there for three years, Eva found time to be (and I quote from the newspaper again here) Chairman of the Medical Services Sub-Committee of the Education Committee, Chief Patrol of the Women’s Patrols under the Chief Constable, Hon. Secretary of the Women’s Suffrage Society, member of the Surrey Insurance Committee and the Guildford Education Committee, and the deputy-Chairman under the Medical Officer of Health on the Maternity and Infant Welfare Committee.

It can come as no surprise, therefore, that when William and Eva Hartree returned to Cambridge in 1919 she ‘hit the ground running’ and we can imagine the delight with which those other Cambridge university women welcomed her back. The long, long fight of the suffragists was bearing fruit, as the ban on women voting was being lifted, albeit in stages, and modern Cambridge was taking shape.

In 1921 Eva was put forward as a candidate for the quaintly named ward of Cambridge Without, which included the northern part of Trumpington parish (the village itself was not included in Cambridge until 1934). She was one of 78 councillors, five of whom were women. The town council that Eva joined was involved in a host of civic services, some familiar to city councillors of today, others now the responsibility of other organisations. We see evidence of this if we look at the Council minute book for 1924, which documents the appointments to roles such as the librarian, coroner, bacteriologist, Keeper of the Corn Exchange (the wonderfully named Ebenezer Pike), sewage farm manager, Female Searcher at the Police Station, and Custodian of the Bathing Shed.

Although Ada Keynes was the first woman elected as a town councillor in 1914, it was Eva, a relative newcomer, who was chosen by her fellow councillors to be Mayor in 1925. I believe that this could have been because her approach to politics had enabled her to work across the boundaries of the political parties of the time and to win their respect. The Mayor acts as the Chairman of the Council, and as we have seen, Eva Hartree certainly had plenty of experience in that role.

So, in 1925 Cambridge Borough Council held an historic mayor-making, and Eva Hartree councillor for Trumpington, was duly dressed in the traditional robes and chain that are so instantly recognisable as those of a mayor in this country. I may be biased, but I consider the Cambridge chain, made in 1897, to be one of the finest around, and it is a powerful link with all the councillors who have served as Mayor of our City since then.

Unlike Eva’s male colleagues, however, she had something special, the Mayoral handbag! History does not record on what occasions she used the handbag, but when I was Mayor in 2002, I took it with me to the service of Nine Lessons and Carols at Kings College, complete with a throat sweet in case a cough stopped me from reading the lesson from Isaiah which is traditionally read by the Mayor of Cambridge. Maybe she did the same.

After the rigours of her mayoral year, Eva Hartree suffered a recurrence of her Graves disease, a thyroid imbalance that had plagued her with fatigue for many years, and she was forced to step down from the Council for three years to recuperate. She was re-elected to what was then called the South Chesterton ward and continued with what was to be 20 years of serving as a councillor.

My investigations have only scratched the surface of the life and times of Eva Hartree but the obituary by E . W . Parsons which can be found in the Girton Review for 1947 gives an idea of the breadth and depth of her achievements

I do hope that you share my admiration for Eva Hartree and agree with me that she was a Trumpington mayor of whom we can be very proud.