Peter Dawson

One of a series of talks titled Trumpington Worthies, given at the Local History Group meeting on 29 November 2001. There are also pages about the funeral of Henry Fawcett, notes about Henry Fawcett, and Millicent Garrett Fawcett and Women’s Suffrage.

Picture a fine September day in 1858. Three men are out shooting pheasant. They’re in a thick covert. One sees a movement, takes aim quickly and fires. There’s a cry of pain! A father, who suffers from cataracts, has accidently shot one of his sons. By a cruel twist of fate, of the multiple pellets that have struck the young man, only two have caused injury – one in each eye, rendering him permanently, totally blind. But this was no ordinary man. Once realisation had set in, with courage and determination which were to be the hallmarks of his amazing career, he declared, “Well it shan’t make any difference in my plans of life!” His name – Henry Fawcett.

Let me take you back 25 years from that fateful day. The father, William Fawcett, a draper who became Mayor of Salisbury in 1832, was a supporter of the Reform Bill and the Anti-Corn Law League. He later became a farmer. Henry was born in that city on 26th August 1833. Their house looked onto the market-place, a source of great fascination to young Henry. Here were sown the seeds of his later ambitions.

He learned his letters at a dame school where the teacher claimed, “I never has so troublesome a pupil – his head was like a colander.” In 1841 he was sent to a school at Alderbury, near Salisbury, kept by a Mr Sopp, where, being an athletic lad, his heart lay more in the countryside than in the classroom. However, in 1847 Henry entered Queenwood College, recently opened as an innovative agricultural school, where he learned chemistry and surveying and was encouraged to write essays on economical and other questions. Local people thought him mad as he wandered around reciting poetry.

In 1849 he was sent to King’s College School, London. His interest in politics was encouraged by a Mr Fearon with whom he lodged and who was an office keeper in Somerset House. This enthusiasm was further inspired by visits to the Public Gallery at the House of Commons. Henry did not especially distinguish himself at school but won prizes and was recommended by the Dean of Salisbury for a Cambridge career.

He entered Peterhouse in 1852, migrated to Trinity Hall the following year and graduated BA in 1856 achieving seventh place in the Mathematical Tripos. His childhood desire for a political career was stimulated by active participation in debates at the Union and the influence of radical political views of the likes of John Stuart Mill and others. He didn’t allow his skills at games of chance and his athleticism interfere with serious study.

Henry entered as a student at Lincoln’s Inn in 1854. Two years later he was elected to a fellowship at Trinity Hall. He lived in London from 1856 until the shooting accident after which he returned to Cambridge making rooms in Trinity Hall his headquarters for some years. Here he studied political economy and joined the Political Economy Club. He was regarded as a brilliant liberal speaker, his reputation being raised by the publication in 1863 of his “Manual of Political Economy”. In spite of his radical opinions and blindness, that year he was elected Cambridge’s first Professor of Political Economy and lectured regularly until his death.

In the 1860s he was to be struck again by two missiles – fortunately nothing more dangerous than Cupid’s arrows. Firstly, he proposed marriage to Elizabeth Garrett, the first English woman doctor, 13 years his junior but a great admirer of his keen mind, zest for living and his determination to get into the House of Commons. She was impressed too by what she called “his gift for good talk and incapacity for being awed by differences in status”. However, in her biography she pulled no punches, describing Henry as “very tall (he was 6ft 3ins) with a massive head and ugly”.

For whatever reason, there was to be no engagement, perhaps because her elder sister Louisa advised against it. They remained close friends and Elizabeth went on to achieve greatness herself in the field of medicine. She married James Skelton Anderson and later, in Aldeburgh, became the first woman mayor in England in 1908 at the age of 71.

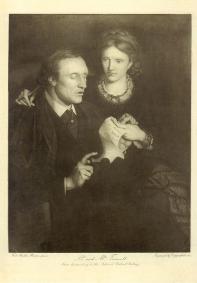

Romance was still in the air, however, when Henry, on hearing Elizabeth’s younger sister Millicent speaking, wanted to meet, as he put it, “the owner of that voice”. They married on 23rd April 1867. She supported his principles, shared his intellectual and political labours and was the main source of his happiness and success in later life. Millicent, in turn, was encouraged by her husband to pursue her own career as a writer. Henry supported her work for women’s rights, becoming president of the National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies, a position later held by Millicent herself.

His wife continued with her good works for many years, helped to found Newnham College and was made a Dame of the British Empire in 1925. She died in 1929 aged 82.

In 1875 they took a house in London where Henry stayed during parliamentary sessions but also had a house, where he resided when lecturing, at no. 18 Brookside, just off Trumpington Road in Cambridge.

Henry’s political career began in earnest when, in 1860, encouraged by Mill, he proposed himself as parliamentary candidate for Southwark. Although unknown to the constituency, his brilliant oratory brought crowds from all over London and, although he had to withdraw his candidacy, his fame was spreading, particularly among politicians. He stood for Cambridge in 1863 but was beaten by a small majority. The next year he stood for Brighton, was narrowly beaten again but was elected there to Parliament as a Liberal in 1865 aged 32.

He quickly established himself as a vigorous MP, advocating votes for women and the abolition of religious tests at universities. He supported social reforms for factory and agricultural workers. Re-elected for Brighton in 1868 he joined a group of radicals, became a conspicuous critic of the Liberal government and eventually alienated himself from the party. In 1873 he helped to defeat Gladstone when opposing the Prime Minister’s scheme for dealing with university education in Ireland denominationally instead of by united education.

Henry lost his Brighton seat in 1874. There was widespread regret, evidence of the respect he had earned through his independence. Later that year he was elected as member for Hackney.

Although blind, his love of the countryside motivated his energetic campaign to save common land, including Epping Forest and the New Forest, from enclosure.

He also championed the cause of the depressed people of India, astonishing listeners to his speeches by his amazing command of complex facts and figures. He became known as “the Member for India”.

During the 1874-1880 Parliament Fawcett became reconciled to his party, his geniality and independence having gained great respect.

In view of today’s international events it is intriguing to know that Henry Fawcett joined the Afghan Committee in the 1870s to help rouse public opinion against the war in Afghanistan.

Re-elected for Hackney in 1880, he became Postmaster-General in Gladstone’s government, but a seat in the cabinet was withheld, partly on account of his blindness. This position prevented him from criticizing the government but, on another topical note, he was utterly opposed to Home Rule for Ireland.

As Postmaster-General he introduced many new measures – the establishment of parcel post in 1882, the introduction of postal orders, cheap telegrams, terms for telephone companies and Post Office Savings schemes.

He proved to be an efficient administrator, conscientious and good-natured, who sought to protect the welfare of his employees. Moreover, he employed women medical officers and continued to clash with Gladstone over his refusal to give women the vote.

His connection with Cambridge had always remained strong – he came close to being elected Master of Trinity Hall.

In November 1882 Henry Fawcett suffered an attack of diphtheria. His sister-in-law, Elizabeth Garrett Anderson, helped to nurse him and he apparently made a complete recovery only to catch pneumonia in October 1884. He died in Cambridge, after a short illness, on 6th November aged only 51. He was buried in Trumpington Churchyard on 10th November in the presence of a great crowd of friends, colleagues and representatives of many public bodies. Their carriages stretched right back to Cambridge. His wife Millicent and their only child Philippa, then aged 16, led the mourning.

Henry Fawcett had many honours bestowed on him. He was created Doctor of Political Economy by the University of Würzburg, was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society, a Member of the Institute of France and given an honorary degree by the University of Glasgow where he was elected Lord Rector.

In Westminster Abbey there is a monument to Fawcett, raised by national subscription. From this fund a scholarship tenable by the blind of both sexes was founded at Cambridge and a playground provided at the Royal Normal College for the Blind, Norwood. In Salisbury, a statue to him was erected in the market place and a memorial placed in the Cathedral. A drinking fountain commemorating his services to the rights of women was erected on the Thames Embankment.

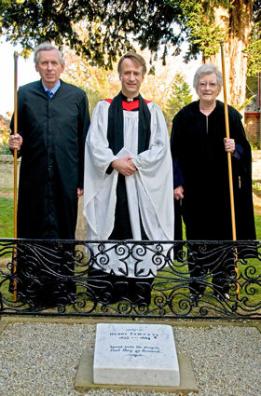

In Trumpington the village school is named after Henry Fawcett and the Church has its very fine stained glass window in memory of this remarkable man. Is it not sad then that his grave, with its rusting wrought iron surround and modest stone bearing the barely legible inscription “Speak unto the people that they go forward”, should be in so neglected a state [in 2001]?

Throughout his life Henry Fawcett, from all accounts, displayed many great qualities: his kind- heartedness, independent spirit, chivalrous nature, strong principles and tireless energy were always in evidence. He had a wide circle of friends, being a genial companion at ease with people of all ranks.

Despite his blindness he remained remarkably active. While at Cambridge he rowed in a don’s crew named “The Ancient Mariners”. He was a strong walker and enjoyed walking on the Gogs. He was also a powerful skater, could skate to Ely at 15 mph and was able to skate 50 or 60 miles in a day even towards the end of his life. He would ride at the gallop on Newmarket Heath and was a skilful angler and, perhaps above all, never lost that love of the countryside which, all those years before, had so frustrated a bright-eyed young boy gazing out wistfully through a dame school window.

Postscript

In 2004 Trumpington Local History Group sought permission for a blue plaque in Henry Fawcett’s honour and raised the necessary money. The blue plaque was unveiled in a ceremony in Trinity Hall and later affixed to Number 18 Brookside. The Group then turned its attention to the grave and again Peter Dawson led the fund raising. The renovation was finally completed in October 2008 and there was a simple rededication service on 1st April 2009.

The grave was again renovated in early 2018, when the headstone was adjusted to make it more visible (The Trumpet, April-May 2018, p. 21).