I have been looking at the census returns for Trumpington from 1831 to 1901, in order to find out about some of the working families of the village and where they lived.

This is one of a series of pages about farms and farming in Trumpington, based on presentations at the meeting of the Group in October 2009. See the introduction to farms and farming for more information.

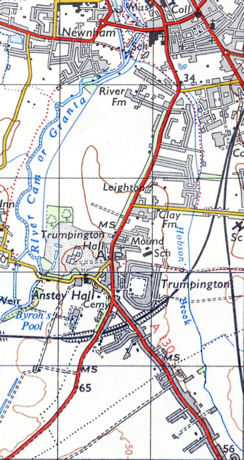

There were six farms in Trumpington that can be identified in the census records:

• River Farm, now at the end of Latham Road

• Clay Farm, off Long Road

• Anstey Hall Farm, in Grantchester Road

• Church Farm, or Home Farm, in Maris Lane

• Manor Farm, no longer standing, which was just north of the Village Hall

• Glebe Farm, or Vicarage Farm, off Shelford Road, now at the end of Exeter Close

In the 19th century, although four of these farms were on Pemberton land, none were farmed directly by the family, and all had tenant farmers or farm bailiffs in them. The farmers I have been able to identify in the census returns are listed below.

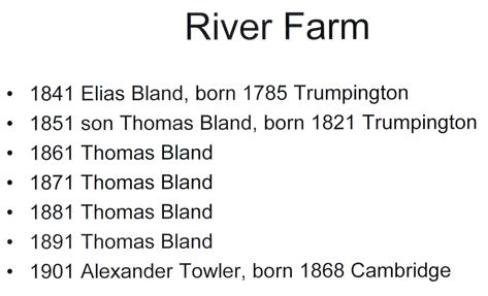

River Farm was tenanted for most of the time by the Bland family, and identified as “Bland’s Farm”.

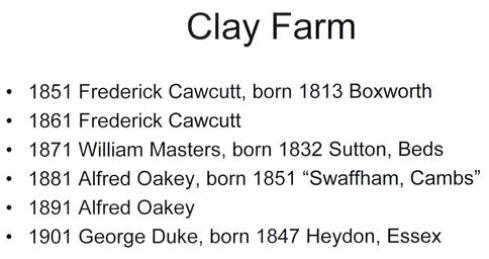

Clay Farm had a succession of different farmers, all from outside the village.

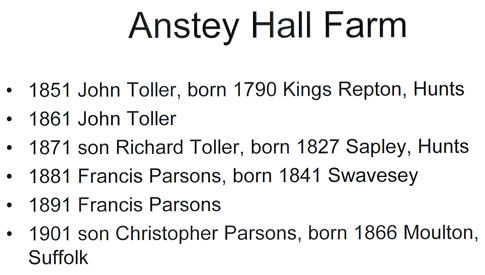

Anstey Hall Farm had tenants of the Fosters in Anstey Hall, the Toller and Parsons families.

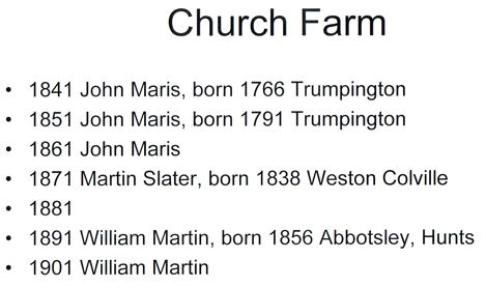

Church Farm, otherwise known as Home Farm or Maris Farm. The Maris family were tenant farmers here for three generations; the grandfather John came from Great Shelford in the late 1700s, and then his son John and grandson John farmed here until the 1860s. (Thanks to Ken Fletcher for information about the genealogy of the Maris family.)

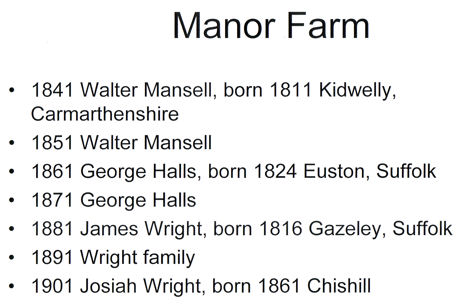

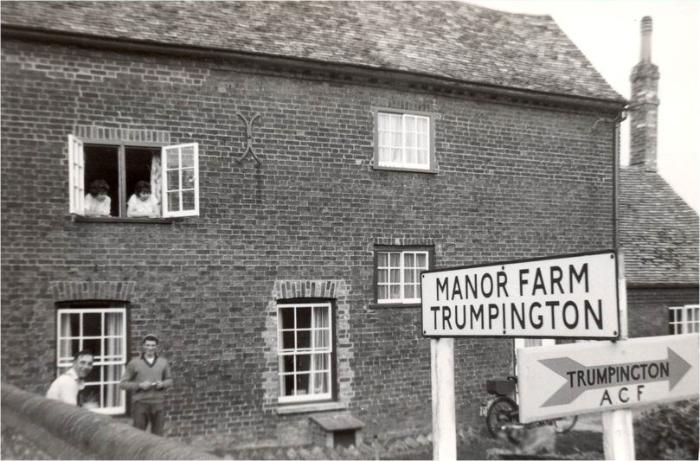

Manor Farm, which was knocked down when Beverley Way was built. This has proved to be quite difficult to pin down, as it never appeared in the census named as a farm, and no farmer was recorded living near the Tally Ho public house. However, a succession of farm bailiffs were recorded close by, and I have had to make the assumption that these are the families living there. I would welcome any further information on the inhabitants of Manor Farm.

Manor Farm, Trumpington, 1964. Photograph from Kathy Eastman, Trumpington Past & Present , p. 34.

Maris House. Photograph from Peter Dawson, Trumpington Past & Present, p. 92.

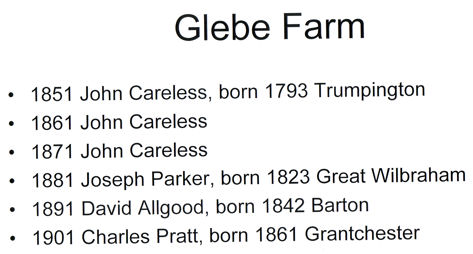

Glebe Farm, or Vicarage Farm (or as it appears one year, Parson’s Farm, which was very confusing as the Parsons family were tenants of Anstey Hall Farm for many years). This was another farm without farmers, but a succession of bailiffs or, in later years, labourers, occupying the house on what was land belonging to the church.

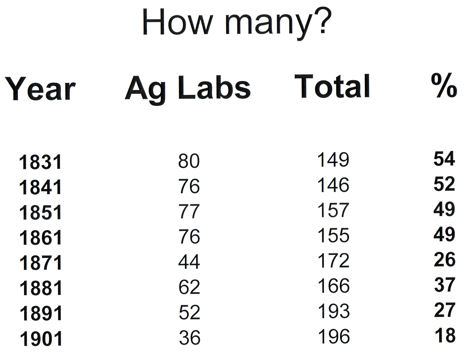

So that’s who was running the various farms. What about the workers? The census returns show very clearly the extent to which Trumpington was an agricultural community. Here are some actual numbers. I have included the 1831 census: the actual returns for that year have not survived, but the statistics were published, and appear in Edith Carr’s history of Trumpington.

The census records the occupations of the heads of households. In the early 19th century, over half the men of the village were “Ag Labs” (agricultural labourers). As the century progressed, the numbers and proportion of those working on the land went down.

Why was there a decrease: mainly because of gradually increasing mechanisation, and the need for fewer labourers. But also the area of land under agriculture slowly shrank, with new houses being built, particularly the grander ones in the north of the parish, which took quite large chunks of land out for their gardens.

In the earlier years, these workers appear on the census as either just “Ag Labs” or plain “labourers”. The only obvious specialisation is that of Shepherd, and there was a very consistent number of four or five shepherds in the village all the way through the century. By 1901, though, specialisation started to appear.

There is one anomaly in the gradual decline of those working on the farms. If you look closely at these figures, you can see that something strange happened in 1871. This was due to coprolites, which are essentially fossilised animal dung, and are very rich in phosphates, making them suitable for grinding up and using as fertiliser.

In the case of Whitelock’s Yard in 1871, the heads of all of these households were not “Ag Labs”, but “Coprolite Labourers”. This was a phenomenon that was county-wide during the 1860s and 1870s, after the discovery that coprolites were there just for the digging under the chalk layer, just above the Gault sand.

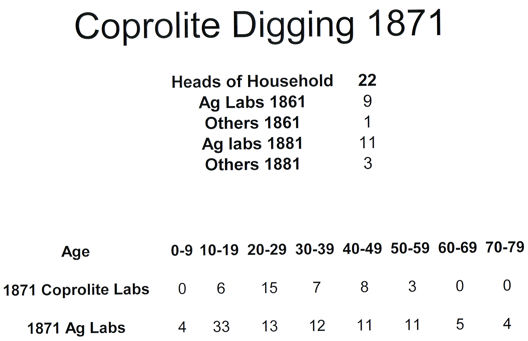

The need for corprolite labourers resulted in a sudden dip in those working in agriculture in 1871, though of course these 10-yearly snapshots can create a more dramatic change than was really the case. This table takes some interpreting, but basically shows that most of those who were coprolite diggers in 1871 were “Ag Labs” ten years earlier and then found themselves back in agriculture ten years later.

Look at the ages of those who were Coprolite labourers (not just heads of household this time, but all those in Trumpington), compared with the Ag Labs of the same year. The average age is almost exactly the same for both groups. But the coprolite labourers were mainly men in the prime of life, whereas the Ag labs spanned the complete working age range for the time, from 8 to 78. I’m sure this is because digging for coprolites was really back-breaking work, which only a fit, strong, relatively young man could do. Work on the farms, though, was much more varied, and many jobs could be done by the very young or the old.

Another change was associated with the decline in agricultural employment towards the end of the century. This is shown in Alpha Terrace in 1901, when there were a number of gardeners living there. This coincided precisely with the growth in the number of large houses in the area, and the need for someone to look after those big gardens. Many of these gardeners were at one time working on a farm, and many of the skills would, of course, be transferable.

Clay Farmhouse, 1937. Photograph from Rachel Tarry, Trumpington Past & Present , p. 26.

Trumpington in the 1950s, Ordnance Survey