Dr Joanne Sear

This paper was published in January 2024, as an extended version of the presentation given by Jo Sear to the Local History Group at the meeting on 16 November 2023.

Introduction

This paper gives a flavour of what the Catholic religion meant to people in late medieval England and, perhaps more particularly, how people in late medieval Trumpington engaged with its teachings and practices until the Reformation brought significant changes to the religion of the people of England.

Religion in Medieval society

The Act of Supremacy, passed in 1534 during the reign of Henry VIII, recognised the king as the Supreme Head of the Church in England with ‘full power and authority’ to ‘reform’ the institution and ‘amend’ all heresies. This marked the beginning of the English Reformation, with England formally breaking away from the pope and the Roman Catholic church and becoming a Protestant nation. As well as rejecting the authority of the pope as head of the church, the adoption of Protestantism led to a number of other profound religious changes in England, some of which took longer than the reign of Henry VIII to come into effect. There were many changes, but just to highlight a few which are referred to in this paper. The first one is the so-called ‘dissolution of the monasteries’, which did take place under Henry, he disbanded the various religious houses, expropriated their income and disposed of their assets. And then, secondly, the rejection of the doctrine of purgatory. Purgatory, which was so important to the Catholic faith, disappeared with the adoption of Protestantism in England. And then a few which were introduced by Henry’s son, Edward VI, who was far more zealous in his reforms than Henry had been. Iconography, in the form of murals and pictorial stained glass windows were removed from churches. The worship of saints was discouraged. Restrictions were placed on the number of ‘lights’, candles, torches, etc., that could burn within the church. Religious guilds were suppressed.

However, prior to the Reformation, the Roman Catholic church had been the dominant form of religion in Britain for a millennium, from the sixth century to the sixteenth. In the late medieval period in particular, adherence to the Catholic faith was very strong and there are still reminders around us of how important faith was. This paper will discuss the role that the Catholic church played in the lives of late medieval people, and then pull in some surviving evidence from Trumpington to support this.

From the outset, it is important to acknowledge that at a distance of half a millennium, there are limited surviving sources which tell us about the late medieval church in Trumpington. Sources used include wills, together with evidence which has survived in the church itself, and some references in other documents. Unfortunately, one very good source for this sort of study is late medieval churchwardens’ accounts, and, sadly, these have not survived for Trumpington. So Trumpington evidence will be supported with some from nearby Cambridge, and some from other parishes near to Trumpington.

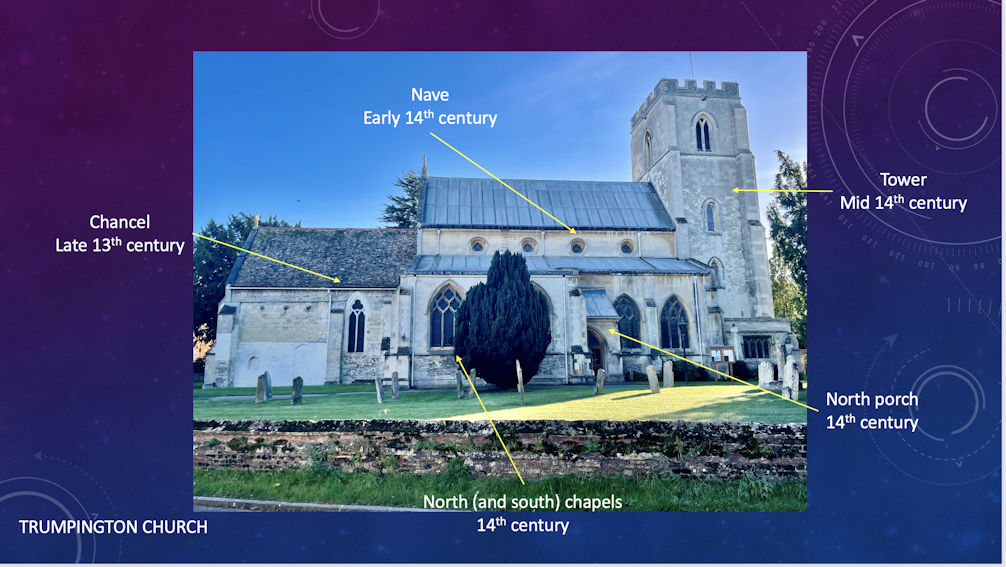

To start with a brief mention of the layout to which most parish churches conform. Very basically, a church consists of two main parts, the chancel and the nave. At the east end is the area known as the chancel, with the main altar at the far east end. The chancel is the most sacred part of the church, generally regarded as the preserve of the clergy and, in the Middle Ages, the rector would have been responsible for any building and maintenance of the chancel. To the west of the chancel is the area known as the nave, the area of the church reserved for the congregation which it was their responsibility to build and maintain. At the very east of the nave is the crossing, invariably with transeptal chapels to the north and the south of the crossing. And then, usually at the west end of the church is the tower. Trumpington church beautifully conforms to this pattern. The aerial photo clearly shows the chancel at the east end, the nave behind it, the two transepts, and then, at the west end, the tower. It is important also to highlight the fact that inside late medieval English churches, as in today’s Catholic churches, the two sections of the church, the chancel and the nave, were very clearly divided from one another by a rood screen. The rood screen would have been surmounted by a rood loft and what was known as the Great Rood, a representation of the Crucifixion with Christ on the cross, Mary to his right and John the Baptist on his left. All roods and all but a very few rood lofts were removed at the Reformation, but more recently some churches have reinstalled them.

For almost everyone at this time, life was difficult. Most people depended heavily on agriculture for their existence and a poor harvest could leave entire communities short of food and liable to starvation. Disease was widespread and the inability to deal even with relatively minor and common ailments and injuries was such that many people lived with some form of chronic disease or disability. Not only was living hard, but there were constant reminders of the proximity of death. High infant mortality, disease, famine, frequent wars and poor standards of medicine, combined with the frequent plague epidemics that marked this period, were such that death formed part of most people’s everyday experience. In circumstances such as these, the church played a fundamental role in people’s lives. It provided two interrelated aspects which made life more bearable: first of all, late medieval religion offered people help and assistance during their challenging lives and the comfort and reassurance that divine beings could provide them with protection against adversity; and, secondly, the church played a vital role in drawing the parish community together, it gave people a sense of mutual support and obligation. It is perhaps no surprise that given this scenario, the late medieval Catholic church, with the pope at its head, had established enormous power and influence across most of the European continent.

At this time, the Catholic church in England, as elsewhere, consisted of two parts, the secular church which was attended by the general population, and the regular church of the monks, friars, etc., where members followed a monastic rule (Latin: regula). The largest of the two parts was the secular church. Whilst this did consist of a rigid church hierarchy, the engagement of most people with the secular church was simply based on a system whereby local priests looked after the souls of the people who lived within their parishes. Integral to the work of the parish priest was the parish church, which was not simply the spiritual hub of the parish, but also the physical heart; they were often centrally located in the parishes they served, and the size of churches was such that they towered over their parishes, making them an easily identifiable landmark. Trumpington church, for example, was built on the highest part of the parish, and although modern buildings now make it quite difficult to see it from across most of Trumpington, the aerial image of the church does give some idea of how dominant it would have been within the landscape, particularly since in the late medieval period, the tower was topped by a steeple. It’s perhaps important to also remember that whilst parish churches provided a community focus for parishioners, their attached churchyards were the principal burial sites for the dead of the parish.

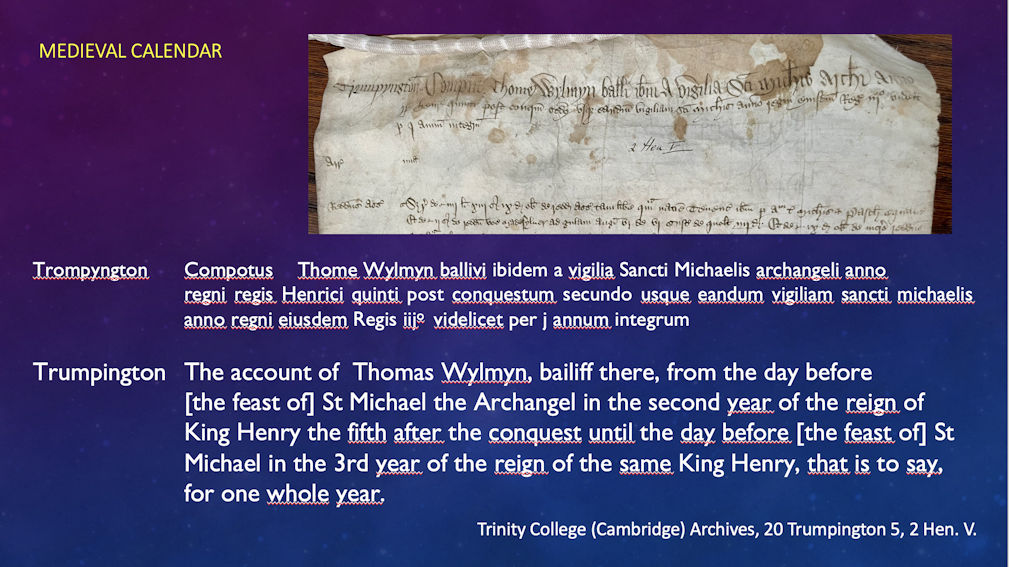

As good Christians, people were expected to observe the seven sacraments of the Catholic church (baptism, confirmation, the Eucharist, penance [or confessing], anointing the sick, holy orders and matrimony). People were also expected to be present at church every Sunday (although there is an ongoing debate about how often they did attend) and to show up at church for certain festivals throughout the year. The church not only dominated the daily life of late medieval Christians, but it also had a significant influence on their life stages. Many of the seven sacraments related to rites of passage which marked the key events of life; the baptism of newborn children, marriage, and the last rites before death. In addition to marking out life stages, the yearly calendar was divided up by religious festivals, such as Christmas and Easter, and even dates associated with farming, together with the feast days associated with the saints. For example, medieval documents were dated by reference to a feast day rather than a calendar day or month. This is demonstrated by the top of an account roll for the manor of Trumpington for the year 1414/15, where the days of the account year are given as the day before the feast of St Michael the Archangel. The Feast of St Michael the Archangel, also known as Michaelmas, fell on what we would know as 29 September and marked the end and the beginning of the agricultural year. As most manors were heavily focussed on agriculture, almost all medieval manorial accounts are dated by reference to the feast of St Michael the Archangel.

It is important to acknowledge that the regular church also had a role in the lives of medieval people. The regular church consisted of men and women who had sworn vows of obedience, celibacy and poverty, and who predominantly lived in communities guided by the ‘rule’ of their founder. A wide range of regular orders were present in late medieval England. Some of these, generally referred to as monks, withdrew from the world into abbeys and priories to live lives of quiet contemplation and prayer. But other orders, generally referred to as friars, freely engaged with their local lay communities by preaching the word of God and caring for the sick and destitute. Regardless of the level of direct engagement with the outside world, the regulars still played an important role in the lives of the laity. The monastic orders sought salvation for all through their devotional work, whilst friars in particular frequently heard confessions, one of the seven sacraments. In addition, religious houses made a sizeable contribution to social welfare including supporting the sick and the poor, as well as providing hospitality to travellers, whilst some houses also provided education to young boys from within the local population. The regulars also played a significant economic role in late medieval society. They were major landowners, so that many people held land or other holdings from religious houses, or simply lived on a manor held by an ecclesiastical lord. In a similar way, many medieval landlords founded markets and fairs, and even established towns on their manors, with religious orders particularly active in this respect, so that even those not attached to an ecclesiastical manor found themselves engaging with a religious house when they bought or sold goods in a commercial setting. Religious houses were also major employers, to the extent that some of the larger houses may have been the most important source of employment within their immediate vicinity. Even if not employed by a religious house, many people sold their produce to religious houses.

The importance of death and the role of purgatory should also be highlighted because this was something that was vital to late medieval Catholics. At this time, death was not regarded as final, but simply as the next stage of the soul’s journey so that the very purpose of life was to prepare for death (in the form of the afterlife). Late medieval Christians believed that when you died, you went to Hell if you were guilty of mortal sins, or if you were not baptised, whereas eternal life in Heaven was the ultimate reward for the good. Only the very bad went straight to Hell, whereas only a very few ascended straight to Heaven. The souls of only moderately bad sinners, which was pretty much everyone, were permitted to go to a physical place that existed between Heaven and Hell and which was known as Purgatory. Once you were in Purgatory, you were eligible to go to Heaven once you had completed your penance through a limited period of suffering. Purgatorial sufferings could be diminished in two ways: firstly, by grace accumulated during life through meritorious acts, particularly those associated with the seven corporal works of mercy; but, secondly, by acts of prayer and devotion performed by living persons on behalf of a deceased person or persons. The doctrine of purgatory was accepted by the Catholic church in the 1200s and was hugely influential in shaping religious culture in England until the Reformation. The belief in Purgatory, and the focus on the ways in which purgatorial sufferings could be diminished, had a significant bearing on the behaviour of late medieval Christians and their engagement with the church.

Religious institutions in Cambridgeshire and Cambridge and their impact on Trumpington

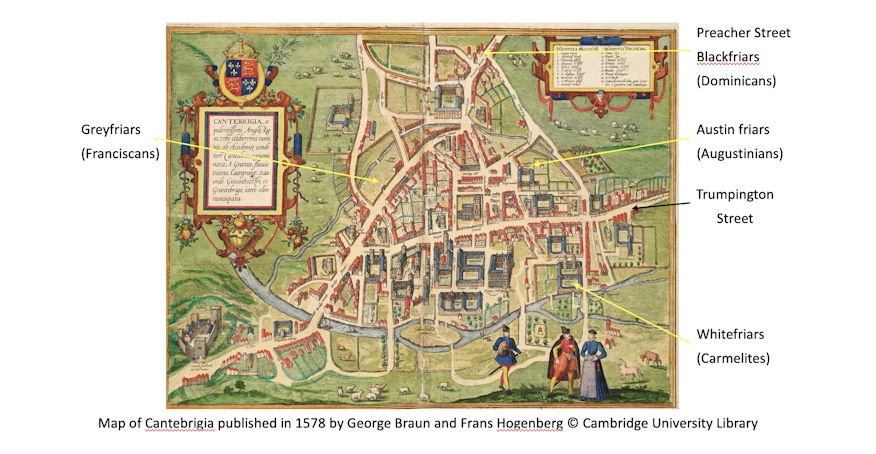

This brief overview of the nature of late medieval Christianity provides a context for the following discussion on religion in late medieval Trumpington. The first part of this is an analysis of how Trumpington people engaged with the regulars; the monks, friars and nuns who all disappeared in England at the Reformation. There were no religious houses within Trumpington itself, however, in the late Middle Ages, as today, Trumpington lay within the diocese of Ely which covered the then county of Cambridgeshire. At this time, the diocese was dominated by the Benedictine abbey of Ely, the church of which was Ely cathedral. The abbey was the second richest religious house in England and held vast estates in the county, particularly in the north and around the Isle of Ely. There were also various houses within Cambridge itself. The most significant of these was Barnwell Priory, a house of Augustinian canons, which lay on quite a sizeable plot just to the north of the town. It’s all disappeared now, except for the Cellarer’s Chequer, the abbey church and a few odd walls. Both the monks at Ely abbey and the canons at Barnwell priory were closed orders, they did not actively interact with local communities; it was the friars that had the most contact with medieval people on a daily basis. Each of the four great Orders of the Friars were represented in Cambridge in sites shown on this early map. The Franciscans, or Greyfriars, had their friary on the site now occupied by Sidney Sussex College. The Carmelites, or Whitefriars, settled first in Chesterton, then in Newnham, then finally on land by Queens’ College which, again, was absorbed by the college at the Reformation. The Augustinian, or Austin friars, held land near St Benet’s Street which is now part of the New Museums Site, and the Dominicans, or Blackfriars, were at the site of Emmanuel College. That’s not actually shown on the map, however, the Blackfriars were also known as the Friars Preachers, and Regent Street, at the top of the map, is marked as Preachers’ Street, and was also previously known as Friars’ Street, giving a clue about their location on the street. In addition, female orders were represented with the Priory of St Radegund which actually held some land in Trumpington. There were also a number of houses of other less well-known orders, many of which were relatively short-lived, including the Ghilbertines, which had the Priory of St Edmund on Trumpington Road.

Mention should also be made of the medieval hospitals within Cambridge, although it is worth making the point that medieval hospitals were not hospitals in the sense that we understand such institutions today. Hospitals existed to provide the spiritual balm to counteract the sinful state which caused physical ailment and were places of prayer and devotion largely administered by regulars, often supported by lay brethren. In late medieval Cambridge, one general hospital had been founded, the Hospital of St John the Evangelist, on the site of St John’s College. There were also two leper hospitals. Most people are aware of the leper hospital associated with Stourbridge Common, the chapel of which is still present, but there was also the Hospital of St Anthony and St Eligius which was on Trumpington Street. This had been founded as a leper hospital in 1361, but by the end of the Middle Ages was probably broadly operating as some form of lunatic asylum. Unlike the other two hospitals, this hospital continued to operate well beyond the Middle Ages, so that even into the nineteenth century it’s former location, just north of the junction of Trumpington Street with Lensfield Road, was known as Spital End.

Religious houses such as these had a significant hold over the lives of people within the county. For example, they held the rectorship of many of Cambridgeshire’s parish churches. As rectors, not only did they receive the tithes of the parishioners, but if they did not wish to serve the parish directly, and very few of them did, they had the right to appoint a vicar to provide for the spiritual needs of the parish in their place. This right, known as an advowson, meant that the holder could largely choose the priest who would serve the parish, a practice which often led to the parish’s requirements being subordinated to those of the patron. The advowson of Trumpington church was held by a number of different religious houses throughout the Middle Ages, but in 1344 it passed to the nuns of Haliwell priory of Middlesex, who held it until the Dissolution. After the Dissolution, Henry VIII granted it to Trinity College at its foundation in 1546 and Trinity has remained the rector since this date.

The religious houses would have influenced Trumpington people in very many other ways, particularly when they travelled into Cambridge. They would have been used to the sight of the friars from the different orders mixing with them in the town centre, and would have been accustomed to giving them donations in return for prayers and to support their charitable works. Many Trumpington people would have attended Stourbridge Fair, at this time the largest fair in Europe, the proceeds of which went to the Chapel of St Mary Magdalene. And, of course, travelling into and out of Cambridge by road, Trumpington people would have passed the Hospital of St Anthony and St Eligius.

Influence of the secular church in Trumpington

However, inevitably, it would have been the secular church that most people engaged with on a daily basis. In return for having their spiritual and communal needs met by the church, parishioners were expected to fulfil the three obligations of maintaining the parish church, ensuring the provision of mass at the high altar, and providing the wages of the parish priest. Members of the parish community were expected to pay tithes to the church on an annual basis with the tax intended to meet these commitments. Looking at the first of these, parishioners were responsible for the upkeep of the structure of the church with the exception of the chancel which was the responsibility of the rector. It is perhaps worth nothing that in the Middle Ages, the dedication of Trumpington church was not to St Mary and St Michael, as today, but to St Nicholas. This is an interesting dedication since St Nicholas, a fourth-century Christian bishop of Greek descent generally known today as Santa Claus, was, and is, the patron saint of sailors and fishermen. Churches dedicated to St Nicholas are often to be found near to bodies of water, and usually the sea, with a number of coastal towns having a church of St Nicholas. There is only one church dedication to St Nicholas in Cambridgeshire today, at Kennett, on the eastern tip of the county. Once again, the parish is on a river, the river Kennett, a tributary of the Lark. The former Trumpington dedication may be a reflection of how important the river Cam was to the settlement in the Middle Ages, principally as a means of transport with water transport being far more important than road transport at this time, but also as a source for the fish which was an important component of the medieval diet.

Trumpington Parish Church

In addition to ongoing maintenance, many communities were keen to embellish and enlarge their parish churches and undertook significant reconstructions during the late Middle Ages and evidence shows that Trumpington people not only maintained their parish church, but were also keen to rebuild it. A church has existed on the site from the Anglo-Saxon period, but most of the building that survives today is late medieval, despite a zealous Victorian renovation project.

The chancel is believed to date from the thirteenth century, whilst the nave, north and south chapels, the north porch and the tower all date to the fourteenth century. And I say ‘believed to date’, because no records survive which detail these building projects, they have been dated from the quite distinctive styles of these parts of the church. However, once we move into the fifteenth century, there is some documentary evidence to support a later development project. Even though the main body of the tower dates from the mid-fourteenth century, work was evidently being done on it right up to the Reformation. In his will of 1504 John Gardener of Trumpington left the quite considerable sum of 40s for ‘mendyng of the botreis of the parisshe church’, another 40s for ‘the reparacon of the Steple’, 40s ‘for the casting and newe ledyng of the said church’, and 3s 4d ‘to the belles’. At around this time, many parishes were adding bells to their church towers and Gardener’s bequests, to a buttress, to the steeple, to new leading for the church roof and to the bells, suggests that this was exactly what was happening in Trumpington. In almost every Trumpington will that has survived from this period, testators give money to the bells, so this was evidently quite a significant undertaking by the parish. There is one other bit of evidence for the project to add bells to the tower of Trumpington church. The old No. 5 bell, which was repaired in 1992 and is now used as a Sanctus bell and rung during the eucharist, was cast in Bury St Edmunds around 1450 and would almost certainly have been added to the tower at this time and as part of the project to add bells to the church tower. The buttresses referred to by Gardener were being added to the tower to enable it to take the weight of the new bells, whilst other changes to the church tower required repairs to the roof. Finally, the project was topped off by the addition of what Gardener refers to as a steeple, but which was probably a spire added to the top of the tower. It is no longer there, but was probably just a wooden structure covered in lead, and similar to that which still exists on the top of nearby Grantchester church.

Projects such as these were invariably led and financed by the wealthier members of society, but they were actively supported by the local community and funded through a variety of means. Activities referred to as church ales, May ales and May games were regularly held throughout England to raise funds for church projects. There is evidence that events such as these were taking place in Trumpington because in his will of 1513, the then vicar of Trumpington, William Hayward, refers to 6s 8d which the parish had raised in May money towards the making of a pulpit in the church. Sadly, that pulpit, if it was ever installed, is long gone, but the reference does confirm that the parish was holding communal events to raise money for projects associated with the church.

Money for rebuilding projects such as these was also frequently raised through the sale of indulgences. Indulgences offered remission of some of the penance which was still owed to God after a sin had been confessed and forgiven, and so they were a way in which a sinner could lessen the amount of time that was spent in purgatory. Remissions associated with indulgences could be obtained in various ways, including acts of devotion and pilgrimages, but they were also frequently offered in exchange for gifts of money used to provide funding for rebuilding projects. It was Martin Luther’s opposition to the sale of indulgences by the Catholic church that led to him nailing his Ninety-Five Theses to the door of Wittenberg church, the event which is frequently cited as launching the Protestant Reformation. Although Luther was opposed to indulgences in general, it was the sale of indulgences to help fund and build the new St Peter’s Basilica in Rome that had particularly incensed him. No evidence has been found to date of indulgences specifically associated with church rebuilding in Trumpington, but one has been found associated with road rebuilding. In 1399, the bishop of Ely issued an indulgence to all those who contributed towards repairs of what was known as the common road between Cambridge and Trumpington (now Trumpington Road). Basically, if you paid for a bit of road repair, in return you received some remission of the time that you needed to spend in purgatory.

Moving inside the church. A typical late medieval church would have conformed to the basic layout shown above but would have included not just one main altar, but a number of altars, together with other side altars. All of these would be decorated with paintings, statues, embroideries, hangings and lights, whilst the walls of the church would have been painted, as with the painting of the Doom which still exists within Great Shelford church, and then the windows would have been glazed with stained glass. The parish was required to purchase and maintain all of these church furnishings and the materials required for services, such as the range of vestments worn by the clergy, books, candles, wine, incense, and the various vessels required for masses and prayers. Most parish communities were keen to ensure that the decorations within the church and all of the items used for services were of the highest standard, partly because this was considered appropriate for divine worship, but also because this reflected on the standing and prestige of the parish itself. The parish community of Trumpington was no exception and we still have a few reminders of some of the work that was undertaken both outside and within the church to embellish and adorn it. Perhaps the most obvious feature is the sheer size of the church; it is very large and even today, it dominates its immediate landscape.

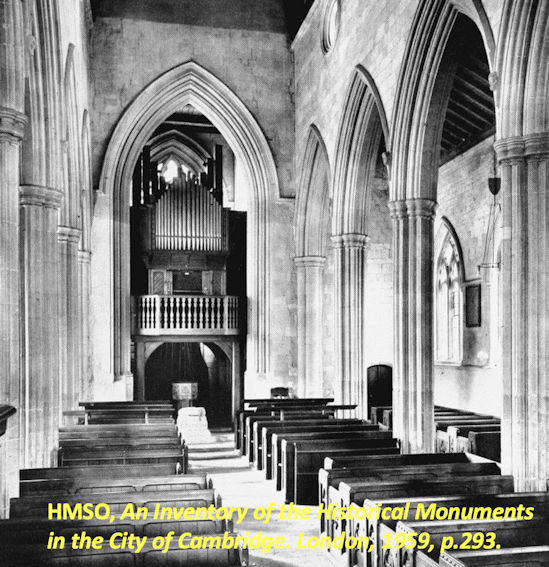

Inside, the nave incorporates five soaring bays, of which three can be seen in the image, whilst the tower arch, shown at the back of the image, is equally impressive. It was evidently built to impress and make a statement.

And then to highlight the rood screen. Only the base of the medieval rood screen survives and in the second image you can still see where the top was cut away and removed at the Reformation. However, what remains is beautifully carved, with a decorative dado incorporating vines, faces, flowers and ears of corn, and although the screen was repainted in 1857, the repainting reflects how the screen would have been painted originally, with red and black panels, stencilled stars and lots of gold leaf. It is a little hard to see since this part of the church is quite dark, but it does give a hint of how magnificent the screen must once have been and is definitely worth a closer look.

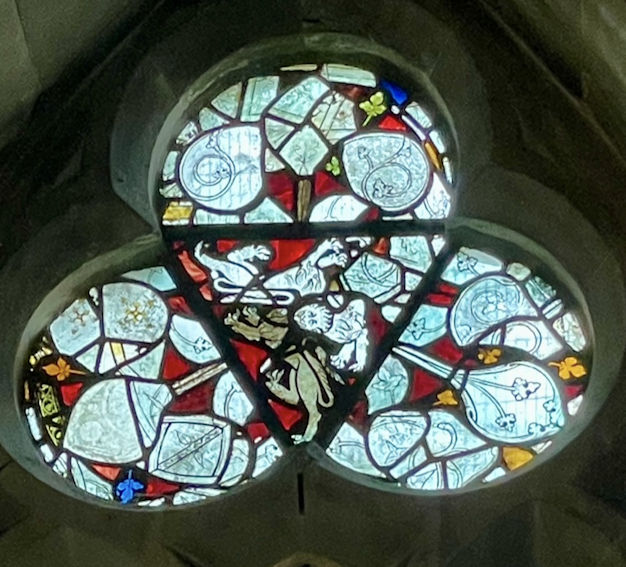

And next, the medieval stained glass. Unfortunately, none of the medieval glass is intact as it was probably broken during the reign of Edward VI and definitely by subsequent iconoclasts to ensure that no images of saints remained. However, within the chancel of the church there are three windows which contain restored medieval glass, albeit somewhat jumbled as they have been reset from fragments. There are some interesting features, and just to mention a few. Firstly, in the centre of the trefoil window on the north side of the chancel is some thirteenth-century glass which depicts an image of three lions or leopards with lolling tongues joined in one head. This piece is believed to be the earliest stained glass still in Cambridgeshire and dates from around 1275. The device of the tricorporated lion is that of Edmund Crouchback, earl of Lancaster, second son of Henry III and brother of Edward I, who is said to have held land in Trumpington.

In the windows below the trefoil window are images of St Peter and St Paul sitting within niches. Inevitably their faces are missing, again almost certainly destroyed because they were depictions of saints, but you can make out St Paul’s book and his sword. The deep colours and detail of this and the other medieval glass in the church, even though it is all a mix, indicate that it was of the highest quality.

And then, finally, to highlight the font which dates from the late fifteenth century and is a beautiful example of an octagonal font, with quatrefoil panels and head corbels. Although it has been partly recut, it is still in excellent condition and the detail of the stone carving is quite extraordinary.

An inventory of church goods for Trumpington does exist from 1300, but whilst it does list the goods held, it does not go into detail about the quality of the materials used to make them. An inventory from nearby Great St Mary’s, Cambridge, dated 1504, does, and gives some idea about the high quality of late medieval church goods. At this time, Great St Mary’s had five separate altars which, between them, held a very wide range of liturgical and venerating items including objects of gold, silver-gilt, silver and pewter; and cloths and vestments made from cloth of gold, satin, velvet, damask and sarsenet, many of which were embroidered with goldwork and decorated with pearls. It would be safe to assume that the items within Trumpington church were similarly opulent.

Parishioners were particularly keen to ensure the provision and maintenance of ceremonial lights in the church. Light has long been associated with good and it is no surprise that it became a key feature of the expression of late medieval piety. Lights burned throughout medieval Catholic churches, especially before the image of Jesus on the rood, before the holy sacrament, and before each of the images in the church. Lights were also associated with the celebration of mass, religious festivals and funerals and parishioners were expected to pay an annual light-scot to maintain the lights within the church, and also to donate a candle at Candlemas on 2 February. The importance of the various lights within the church is also reflected in a number of documentary references to them. So, for example, in 1279 rent from seven acres of land within the parish was used to provide three lights within the church. There are also plentiful examples of bequests to lights in Trumpington wills. John Lakers gave 12d to the torches in 1519, and two years later John Layn gave 3s 4d.

Lights did not disappear completely at the Reformation, those on the altar, in the rood loft and before the Easter sepulchre were allowed to stay. However, one of the most essential features of late medieval Christianity did disappear completely at the Reformation and that was the faith in saints. Saints were the focus of significant veneration and devotion and their images were to be found throughout churches in the form of paintings, statues and incorporated into window glass. The surviving images of Saints Peter and Paul which can be seen in the medieval window glass in the chancel have already been referred to, but there are a couple of other reminders of the veneration of saints in Trumpington. For example, the north and south sides of the tower still contain odd little alcoves at about first storey height. These are statue niches and would have contained statues of saints in former times although there is no record of which saints the statues would have been. Other examples still exist in a number of churches in the area, including Great St Mary’s, where you can see the two empty statue niches either side of the east window, whilst a more extreme example is the gatehouse to the former Benedictine abbey at Bury St Edmunds, dated to around 1353. The twenty plus niches on the gatehouse would all have contained statues of saints.

The most widely venerated saint was Mary, the Blessed Virgin and mother of Jesus. Manifestations of Marian devotion were widespread. Churches, chapels and religious guilds were frequently named in her honour, whist feast days associated with her were some of the most popular within the calendar. Within churches, a Lady chapel dedicated to her worship became popular from the mid-thirteenth century, and paintings and statues were also to be found in addition to the image of Mary which featured on the rood screen. And there is evidence that Trumpington church had a side chapel dedicated to Mary with an altar and image of her, since in her will of 1509, Agnes Paruys of Trumpington asked to be buried ‘before thymage of oure blissed lady at hir aulter’. Chapels dedicated to St Mary tended to be on the south side of the church, so in all likelihood it was this chapel, on the south side of Trumpington church, which was formerly the Lady Chapel.

Many of the relics, images or places associated with saints were the focus of pilgrimages. Pilgrimages were taken for a number of reasons, perhaps primarily because a contribution to a visited shrine earned the donor an indulgence, but visitors also requested healing, sought miracles, or gave thanks for one which had taken place. As they are today, Rome, Jerusalem and Compostela were all popular international pilgrimage sites and there were major national shrines such as those at Walsingham and Canterbury. However, many relics were held by more humble parish churches so that a pilgrimage to a shrine might only require a trip to a local parish church, or even to one nearby. Again, although no record survives of any relics held by Trumpington church, Great St Mary’s held a bone of St Lawrence and oil of St Nicholas, and it seems highly plausible to suggest that Trumpington people would have visited these relics. Trumpington pilgrims probably also travelled further afield, perhaps to the shrines of St Etheldreda at Ely cathedral as the mother church of the diocese, or to that of St Edmund at Bury St Edmunds. Less frequently, relics could also be owned by individuals as well as by churches, so that Agnes Paruys, previously mentioned, also left in her will ‘a tablett of silver overgilt with Relikys’, but she doesn’t give any information about the exact nature of the relics in question.

Other meritorious acts associated with the seven corporal acts of mercy

Many of the activities that I have highlighted, such as building and maintaining churches, pilgrimages and the maintenance of lights, were all regarded as meritorious acts by which a living person would accumulate grace and ease the amount of time spent in purgatory, but so far the ones that I have mentioned have mainly been associated with the church. Meritorious acts were also associated with the seven corporal acts of mercy; feeding the hungry, giving drink to the thirsty, giving hospitality to the stranger, visiting the sick, clothing the naked, ransoming prisoners, and burying the dead. Late medieval Catholics believed they would be judged by their adherence to the seven corporal acts of mercy as concern for the less fortunate members of society weighed in the balance at the Last Judgement. As a consequence, pious and charitable gifts were frequently given in accordance with the seven acts both during life and after life as testamentary bequests. Particular emphasis was placed on the giving of alms to the poor and there is abundant testamentary evidence of grants by Trumpington people including gifts of money, clothing, fuel, bread and ale, or of other forms of benevolence. A couple of examples. In 1504 John Gardener asked that his sons buy yearly for a total of ten years:

‘heeringes price 6s 8d to be dealed in almes to the poore people yerely during the said yeres within the church in lenton season’.

In 1527 Robert Glandefeld, clerk vicar of Trumpington asked that his executors:

‘deale at my moneth daye peny dole to every persone that commith to the same’.

Some Trumpington people were also keen to remember the sick and in his will of 1513, William Hayward left 40d ‘to the spitilhows in Cambrige’, which would have been the hospital on Trumpington Road referred to earlier.

Gifts such as these can clearly be regarded as charitable gifts in accordance with the seven corporal acts of mercy, but people also frequently gave bequests to build or maintain bridges and highways and it’s worth noting that at this time no person or agency was specifically responsible for providing or maintaining highways. The Highways Act, which placed the burden of upkeep of the highways on individual parishes, was not passed until 1555, with one of the reasons for its introduction being the fact that following the Reformation, people were less inclined that their pious forbears to give to road repairs. Before the Reformation, however, bequests to maintain roads in Trumpington were surprisingly frequent. So, in 1521 John Cotton gave five quarters of barley:

‘to the high weyes … betwixt Pamentes gate and Dagnele ende’

There is no other evidence for the location of Pamentes gate, but Dagnell End was a sub-hamlet of the medieval village no longer in existence close to the present Trumpington Hall. In 1504, John Gardener had also given to the road to Dagnell End, in this case a quite sizeable sum of 34s 4d:

‘for mendying of the street that is to wite fro Dagnale ende to the churchegate’

He also gave 20s to the:

‘mendyng of the high wey fro the said gate unto Stokton crosse’

Stokton cross was sited where the present war memorial is, so, in effect, Gardener was leaving money for the repair of Church Lane. Whilst Trumpington wills contain lots of bequests to the highways within the parish, only one has been found to bridges and surprisingly it is not to a bridge over the Cam. In 1521 John Layn left 3s 4d to the bridges in the moor within Trumpington. Trumpington moor was low-lying land which lay either side of Vicar’s Brook, now usually called Hobson’s Brook, so this was a bequest to bridges over the Vicar’s brook.

Whilst gifts to maintain highways or bridges might appear to have been rather more secular, the benefactors clearly regarded them as having a religious significance and, in all likelihood, that significance was that someone travelling along the repaired road might say a quick prayer for the person whose benevolence had led to its better maintenance. Which brings us back to the Stokton Cross, referred to in John Gardener’s will of 1504. When the foundations for the Trumpington war memorial were being dug in 1921, a large stone was discovered which proved to be the base of the former village cross and which now sits under a table at the back of the church. Around the base of the stone is a Latin inscription which translates as ‘Pray for the souls of John Stokton and of Agnes his wife’. The cross was clearly deliberately placed where people would be passing on the road into Cambridge with the purpose that when they saw the cross and the inscription, they would offer up a prayer for John and Agnes which, in turn, would limit their time in Purgatory.

This idea that the time that the soul spent in Purgatory could be diminished by acts of prayer performed by the living on behalf of the deceased also meant that the practice of erecting some form of memorial at the place of burial became increasingly popular during this period, again, so that the deceased would be remembered in the prayers of the living. This was an expensive undertaking so that this practice was largely reserved to the wealthiest members of society who erected grave markers in the form of commemorative brasses and stone sculptures. There is one quite significant commemorative brass within Trumpington church, although, ironically given that these were designed to secure prayers for the deceased person, there is some uncertainty as to who the brass represents. It lies on the top of the chest-tomb between the north chapel and north aisle. From the style of armour displayed on the brass, it had been thought to represent the Crusader Roger de Trumpington, who died in 1289, but is now thought to commemorate his son, Giles, who died early in the fourteenth century. The suggestion is that the brass was prepared for Roger, but then reappropriated for his son.

Wills also frequently contained bequests which aimed to ensure that masses and prayers were celebrated both for the soul of the testator, and for the souls of those who had gone before. Bequests for masses and prayers within Trumpington wills are very common, for example, Andrew Williamson left £6 13s 8d for post mortem masses in 1520. A further way in which people could ensure that prayers were said for their souls was to have their name included on the bede roll, the list of deceased parishioners which formed the focus of prayers by the congregation. A bede roll was simply a list of names which would be read out in a religious setting and those present would remember those on the list in their prayers. The Trumpington bede roll has not survived, but there is lots of testamentary evidence to confirm its existence. In 1531, for example, William Lakere of Trumpington left ‘to the vicar or curat of Trumpynton for … the bed roll 4d’.

The importance of prayers for the deceased is also reflected in donations to religious houses, which were given by people with the expectation that the regulars would remember them in their prayers. Religious houses were a significant focus of testamentary bequests and most of these were to institutions which were local to the testator and would have been well known to them. Trumpington people were particularly keen to remember the four orders of friars within Cambridge which they would probably have encountered in and around the town. In his will of 1498, William Pychard requested 10s to the Austin friars of Cambridge, 10s to the Dominicans, 10s to the Franciscans and 6s 8d to the Carmelites.

Trumpington anchorite and anchorhold

Whilst Trumpington itself did not have any religious houses, at the end of the thirteenth century a form of monasticism was practised in the parish since it had an anchorite. An anchorite, or anchoress if the person was a female, was someone who withdrew from secular society to lead a secluded and intensely prayer-orientated life which was as basic an existence as possible and devoid from any comforts. Their withdrawal from the world was invariably into a small, four-walled cell, known as an anchorhold, into which they were usually permanently enclosed. Anchorites tended to come from affluent families, but they were supported in their meagre existence by their communities for whom they offered spiritual advice and prayers. They existed in very large numbers across England, particularly in the thirteenth century which is exactly when there is evidence of a Trumpington anchorite. In the Hundred Rolls for Cambridge dated 1279, a rent of 4s 6d from a shop in the marketplace went towards the keep of the Trumpington anchorite. No other details are given; it is not possible to tell whether the person was male or female, or even where their anchorhold cell was located. However, an anchorhold was usually built against one of the walls of the local village church, with the most popular location being the northern side of the chancel. The northern side was the least hospitable, which matched the anchorite’s need for a comfort-free existence, whilst a location by the chancel meant that the anchorite would be able to engage with Mass, often via a squint window. The image is of the outside of the northern wall of Trumpington’s chancel. There was clearly something in this location and although the guide books say that it was a sacristy which was subsequently demolished, the double piscina and blocked aumbrey show that at one time it had incorporated an altar, something that would have been required in an anchorhold. Unfortunately, it is impossible to be definite, but the documentary evidence does at least confirm that there was a Trumpington anchorite, and this was the most likely location of his or her anchorhold.

![Evidence of a possible anchorite cell on the outside of the northern wall of the chancel, Trumpington Parish Church. Photo: Jo Sear, 2023.]](http://trumpingtonlocalhistorygroup.org/wp-content/uploads/MedievalReligion_0016_2023.jpg)

Religious gilds

At the beginning of this paper, the value placed by late medieval Christians on the sense of community offered by their parish church was highlighted. Whilst the wider church congregation was the most important community element within a parish, in most cases this was not the only group associated with the church. Other groupings were often formed to serve a particular purpose within the church, or to raise funds for a special project. However, the most significant of these affiliative religious groups were the religious gilds, also known as parish gilds. These were founded on a parish basis and enabled men and women to come together on a voluntary basis to undertake three main functions: honoring a particular saint and maintaining lights before images and the Blessed Sacrament; securing attendance by members of the gild at the funerals of deceased associates and saying intercessory prayers and masses; and celebrating the saint’s day of the gild through an annual feast, although other social and charitable events were also held. These religious gilds became deeply integrated into their local communities and of all the changes which the Reformation brought about, this is one which must have affected communities quite significantly. Across England, there may have been as many as thirty thousand in existence and it has been estimated that three-quarters of Cambridgeshire parishes had at least one religious guild.

One gild is known to have existed in Trumpington, known as the Holy Rood guild, and bequests to it are frequently given in wills from the late medieval period. Robert Gardyner, for example, left £5 to the Holy Rood guild on the condition that members of the guild continued to say masses for his soul. The Holy Rood guild of Trumpington was evidently quite wealthy since although many guilds met in the parish church, the Trumpington guild not only had its own guild hall, but by the standards of the time it was quite a substantial building. In his will of 1498, William Pychard referred to the guildhall of Trumpington which he had caused to have built, and which had a solar and a chamber under the stairs. A solar was an upstairs room, confirmed by the mention of the stairs, and as regards the building technology of the time, this was actually quite advanced. Unfortunately, although there are records of the guildhall being sold by the parish in 1570, after the abolition of the religious guilds, it is not possible to identify exactly where it was. It is very possible that it has survived and is one of the buildings close to the church but further work is needed on that question.

Discussion at the meeting on 16 November 2023

Q: what evidence is there about the families who left bequests?

A: as examples, we know of John Gardener and Robert Gardyner from manorial records. The Pychard family farmed a large estate and became local landowners. Two of the other testators referred to were clerics attached to the church.

Q: presumably most people would not have the resources to give a bequest to the church?

A: while building projects such as reglazing would tend to be led by the leading figures in the parish, they would have been supported by the wider population, such as by participating in community events such as church ales and May games.

Q: presumably written records such as wills were only left by those of high status?

A: almost all wills were of people who were of high or intermediate status. Most of the Trumpington will-makers from this period can be identified as being holders of manors (or substantial tenants) or involved with the church.

Q: what was the role of women?

A: women tended not to make wills, other than widows who had been left money, where there are a few examples; almost all wills are made by men. Widows may devote themselves to the church as anchoresses or nuns.

Q: what sort of lights were used?

A: lights in the church would have been candles or rushes dipped in oil, with beeswax candles as the highest standard.

Q: what was the local population at this time?

A: Andrew Roberts checked after the meeting: there were 37 households (about 185 people) at the Domesday survey in 1086; the 1327 Lay Subsidy named 48 Trumpington taxpayers, including three of the manor holders and the vicar; the 1524 Lay Subsidy returns show that there were 50 taxpayers.

Comment from Michael Hendy, who remembered taking the Sanctus bell to Whitechapel Foundry in the 1990s. They managed to get the bell down from the bell loft but had too little time when it came to driving to the Foundry in London, so rushed with it down the M11!

Q: what role did the structure of the church play in community life?

A: historians consider that churches would have been an open hall, well used for fairs, etc.

Q: did the population think that purgatory was a physical place? A: the teaching of the Catholic church evolved. In the Medieval period, purgatory was considered to be a physical place and this was formally adopted by the Church in the 13th century.