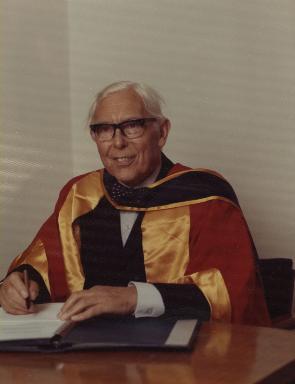

Edmund Brookes

Lord John Fleetwood Baker of Windrush was an eminent civil engineer who lived in Trumpington at 100 Long Road and Crossways Gardens. This paper is based on a presentation given at a Group meeting on 22 November 2012. Updated March 2019 (see footnote).

Introduction

A lot of people are alive today thanks to John Baker. After an initial career as a design engineer on the R100 Airship, he was Professor of Civil Engineering at Bristol from 1933-43, and then Professor of Mechanical Sciences at Cambridge from 1943-68, developing the Cambridge University Engineering Department to today’s position at the forefront of engineering teaching and research. The ‘Baker Building’ in Trumpington Street, opened by Prince Philip in 1952, is his memorial but there are two far more important memorials.

Biography in Brief

John Fleetwood Baker was born on the Wirral in 1901 and educated at Rossall School on the Fylde (probably where his second name came from) where the winds blow from across the Irish Sea. He read what was then known as Mechanical Sciences at Clare College, Cambridge.

His interest was principally, but not exclusively, in structures and civil engineering (in Cambridge, it is basically one department and the students are grounded in all the engineering disciplines). The 1920s was the era of the Great Depression and he initially worked at the Royal Airship Works as an Assistant Design Engineer from 1925-28. This was the private company which built the R100 which successfully flew to and from Montreal in Canada. After the publically built R101 crashed at Beauvais on its first flight to India, the R100, which was more technically advanced, was stored until it was scrapped. In a holiday lecture, I remember Professor Baker telling tales of in-flight repairs on the R100 en route to Canada, but they made the flight/voyage and return to the United Kingdom safely and successfully.

In 1928, he was appointed an Assistant Lecturer at University College until 1933 when he moved to Bristol as Professor of Civil Engineering at the tender age of 32. Obviously his many talents had been spotted early, but he was always a man of easy manner, immaculately turned out with a bow tie and very approachable, taking a great interest in students and encouraging them. He was a people person as well as a brilliant academic.

His big chance came when he was appointed in 1943, again at the still relatively young age of 42, to succeeding the great Professor Sir Charles Inglis as Head of the Engineering Department in Cambridge, a post he held for 24 years until his retirement. In 1943, there was one other professor and 24 teaching staff. By 1968 there were 111 teaching staff and 26 had moved on to be professors at other universities, and over 300 undergraduates started each year. That equated to nearly 10% of the annual undergraduate intake of the whole University.

While at the Engineering Department, he held many other appointments and remained very active after retirement at the then standard age of 67. He lived at 100 Long Road and in later years moved to Crossways House where he would often be seen walking in the Anstey Way crescent, immaculately dressed and wearing his trademark bow tie.

Key Work

There are two projects for which John Baker deserves to be remembered.

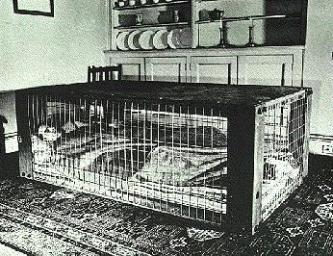

The Morrison Shelter

In the early years of World War II, many people were being killed by being crushed in their homes. When many materials, steel especially, are stretched beyond they elastic limit, they absorbs far more energy than when they stretch elastically. John Baker demonstrated this by dropping a large weight onto a steel bar beneath which was his gold watch. The bar bent plastically and deformed, but beneath it the watch was safe. I saw him do this, with the same gold watch, in Lecture Theatre 0 at the Engineering Department. He deduced that you could make an air raid/bomb shelter to fit in people’s homes which was easy to get into and which protected the occupants by deforming plastically. While he was still at Bristol University he developed the so called Morrison Shelter, which was introduced in 1941 and for which Herbert Morrison tried to take credit for but which in his book ‘Enterprise v Bureaucracy’, Baker finally gets acknowledged as the inventor. The second part of the design which was so brilliant was that the shelter was assembled from a kit of parts using standard materials, nuts and bolts etc that were readily available and did not detract from the War effort, it could be mass produce, it was delivered and assembled easily and quickly by Boy Scouts needing very little training, it could be used as a piece of furniture in lieu of a table, and inside it was effectively a bed.

It was issued free to people earning less than £5 per week or at a charge of £7. Apart from one direct hit, I believe no one was killed while lying in a Morrison Shelter.

The principle of the energy absorbing capacity of materials when deforming plastically is now applied to cars in a way which permits a light but very strong body. It does however deform when hit, and you cannot just bend it back safely.

The Training of Engineers for Industry

Being a great theoretical engineer with a strong interest in research, you might assume that John Baker was not interested on production but this was not the case, as evinced by the way he developed the Morrison Shelter. He knew that most of his engineering graduates went into industry and joined Graduate Training Schemes. He was convinced that unlike the Premium Apprentices of the golden age of railways, many of these schemes were not very good. Nine years before I graduated he asked my Tutor and Director of Studies at Emmanuel College ‘to think out of the box’ (around his ideas of course). The result was what became known initially as The Reddaway Scheme, then the Advanced Course in Production Methods and Management and fortuitously the leader or first tutor was a young Johnian called Mike Sharman, who was equally able to think out of the box, which he did for over 30 years teaching hundreds of students and inspiring them to work very productively as engineers in industry. That one of the first students is now Prof Sir Mike Gregory, head of the Institute of Manufacturing at the Engineering Department is testimony to the brilliance of Baker’s idea and drive. I took Course 8 and will be forever grateful to the three individuals I have named. As you might expect the course was unconventional:

• you were sponsored by a company after passing Mike Sharman’s eagle eye;

• there was no exam or qualification at the end of it;

• the course was 52 weeks long and you only got 2 weeks off, no such thing as university terms;

• you spent the vast majority of the time in factories looking at real problems, then presenting your report/findings to the factory management, you had to complete it, present it and write it up before the next Monday (quite a challenge to a student who might be accustomed to a more relaxed schedule);

• you went wherever Mike thought that best practice could be observed;

• your report on each project was typed and assessed;

• you toured continental industry to see best practice there.

At the end, you were not an expert but you had been bloodied, ‘Can’t do’ was not an acceptable answer and you had a very wide circle of contacts. Most ex students went on to have very successful careers in industry. I have every reason to be grateful to Uncle Mike as we called him affectionately, and of course John Baker.

Conclusion

All that, and the success of the Morrison shelter, is down to Lord Baker’s foresight, his technical expertise, his ability to spot a problem and get the best person to deal with it, but above all his ability to relate to ordinary people, to converse with them and get the best out of them, truly a remarkable man, who befits the many awards and honours bestowed on him.

Footnote

One of the streets in the Clay Farm development has been named Baker Lane.

In March 2019, one of the rooms in the Clay Farm Centre was named the Baker Studio. The caption placed at the entrance to the room reads: John Fleetwood Baker, Baron Baker of Windrush (1901–1985), was a civil engineer. He was the inventor of the Morrison Shelter, used from 1941 by families as a place of safety during World War 2. In 1943, he moved to Cambridge University as a Fellow of Clare College and Professor of Mechanical Sciences and Head of the Department of Engineering. He married Fiona Mary MacAlister Walker in 1928 and, after the move to Cambridge, the family lived in Bentley Road, Long Road and Crossways House, Trumpington. There is a memorial to Lady Baker and Lord Baker in Trumpington Churchyard.