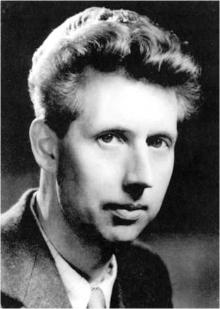

Peter Dawson

Jack Overhill was a man of many parts. This paper is about five aspects of this remarkable man: his early life and education, the hardship he endured, his writing, his philosophy and his love of swimming. It is based on a presentation given at a Group meeting on 22 November 2012.

Early Life and Education

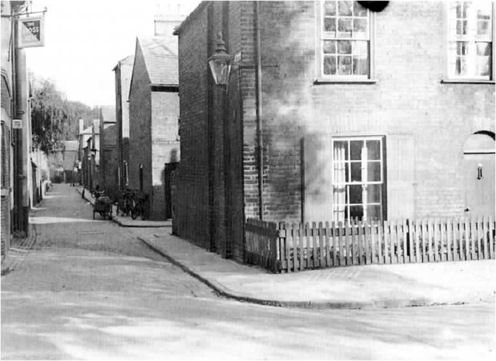

Ellington and Eliza Overhill had 13 children, with Jack, the third youngest being born in Cambridge in 1903. In 1908 the family moved to Gothic Street (between Panton Street and Trumpington Road). Jack acquired strong radical views from his illiterate father, a shoemaker by trade, while reading newspapers to him.

In 1913, they moved to the nearby, larger house, 7 Saxon Street, close to the Spread Eagle and Cross Keys pubs. This noisy working-class neighbourhood was in stark contrast to the elegant dwellings along the adjacent Brookside.

Jack progressed from Elementary to High Grade School in 1914 but family poverty forced him to leave just before his 14th birthday to help in his father’s trade. He studied commercial subjects at night school and taught himself French, Spanish, Portuguese and, later, Italian. He passed Pitman’s Shorthand Teacher’s Diploma aged 20.

From 1920 to 1927, Jack worked as a clerk for W.P. Hollis, a bookmaker. On leaving Hollis, he set up his own Bookie’s business and created one of the country’s first football coupons in the 1920s.

In 1923, he married Histon girl Jessie (Jess) Toates. They lived in 7 Saxon Street until 1927 when Jack bought, and they moved into, 99 Shelford Road, Trumpington. He also bought 7 Saxon Street to keep as an office. He rented a shop on Castle Hill for the shoe repairing business he now ran and he and Jess, with their children, also named Jack and Jess, born in the 1920s, moved back into Saxon Street.

In 1939, Jack purchased a Morris 13.9 horsepower car for £12. Jack began studying for an open degree in Economics from London University. During the war he took the examination four times but failed, having sat no fewer than 36 days or half days of exams. In 1946, by then a grandfather, Jack finally gained his BSc Economics degree, having been allowed to take his one failed paper on its own.

The Overhills moved back into 99 Shelford Road in November 1945, settling here in Trumpington. Jack later lectured on Economics at Cambridge Technical College and taught Shorthand at two Village Colleges. He could be seen often walking his dog along Shelford Road. His wife Jess died at Christmas 1985 after 62 years of marriage.

Hardships

To help relieve the hardship of the times, the young Jack and his brothers would catch sparrows to ‘thicken the gravy’ and often the main meal of the day would be bread and cheese. Odd jobs undertaken by the boys included heavy, poorly paid potato harvesting. Jack worked all day delivering heavy groceries by bicycle on Christmas Eve 1912 for one shilling, half of which his father insisted should be put into Jack’s savings.

Later, Jack’s own family experienced austerity during wartime when there was strict rationing of everything from food and fuel to clothing. Queuing for hours to buy food rations was commonplace, Christmas dinner a rare luxury. Family income was meagre and Jack often borrowed money for essentials.

Jack developed painful splits on his hands through working without mechanical aids, but he still repaired up to 100 pairs of shoes a week. In 1942, his wife began full-time work as an agent for the Prudential to help make ends meet. Jack’s record earnings for a week’s shoe-repairing was £15.18s.6d., of which £12 was clear profit. In 1944, he mortgaged 99 Shelford Road heavily.

On a brighter note, in 1945, Jack, with his son, enjoyed his first holiday since 1913 staying in Brixham, Devon, with his friend Neil Bell’s family.

Writing

After leaving school, Jack began writing short stories for publication. In 1930, the Cambridge Evening News paid him one guinea for a short story. He began writing novels, over 30 in all, but only three were published. These were Romantic Youth in 1933, a story about undergraduates, typically containing Jack’s strong socialistic views, in 1947, The Snob , about a shoe-maker and in 1953, an historic novel The Miller of Trumpington . This, his most readable novel, he researched locally, with special reference to Byron’s Pool, renamed in the book Brian’s Pool after his fictitious hero.

Jack’s work was once likened by a prospective publisher to that of Thomas Hardy’s. The constant rejection of his novels for lack of popularity or paper shortage, although reducing Jack to tears of frustration on one occasion, only made him more determined to succeed, continuing to write his self-imposed target of 1000 words a day. He was encouraged throughout by Neil Bell, a popular professional novelist, who called Jack ‘my mental twin’ in view of their shared political views, ideology and philosophy. In November 2012, a rare copy of the Miller of Trumpington was for sale on the Internet for £150. What would its author make of that?

Jack had ten articles published in East Anglian Magazine in the 1970s. Others appeared in the Cambridge Evening News .

There were two long-term, time-consuming undertakings : The Cash Chronicles , about a family close to the Overhills and Jack’s diary which he kept in great detail every day of his adult life. He gave both these valuable archives to the Cambridgeshire Collection. Jack declared “When I write I’m full of vim. I punch and punch and punch at the typewriter”!

After the war, Jack’s deep resonant voice was one of the first working-class voices to be heard on the radio. He made 54 broadcasts for the BBC, mainly readings from his own works. His 60-minute, unscripted talk entitled A Regular Snob

Philosophy

A teetotaller and non-smoker, Jack Overhill believed in a ‘personal God’ and contended that Christ may not have lived. He was sceptical of the clergy and thought the Bible could be interpreted to suit whoever read it. An avid reader, he preferred works by authors whose Socialist beliefs he shared. Despite this, Jack remained independent of ideological and political organizations. As a Conscientious Objector in wartime, he was spared imprisonment at tribunals for refusing military service, due to his age and his trade being a reserved occupation.

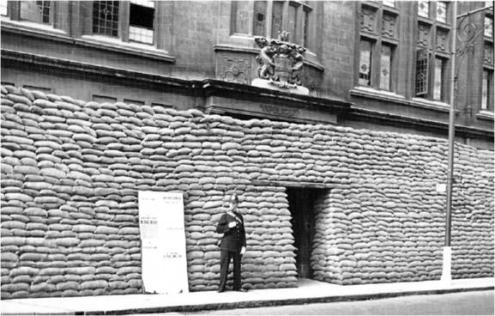

Peter Searby’s 2010 book Cambridge at War, containing Jack Overhill’s diary from 1939 to 1945, reveals the man’s complex personality and his innermost thoughts and fears during that difficult and dangerous time. As a pacifist, Jack believed war only served the interests of the few and was stimulated by arms manufacturers. He said he preferred Democracy to Fascism but not at the price of millions of innocent lives. The closest Jack came to compromising his belief in pacifism was volunteering for fire-watching duties, Cambridge being under the threat of frequent air-raid warnings and bombings. Highly critical of the establishment, he dismissed as propaganda Winston Churchill’s early wartime speech rallying the nation, calling him “a nasty piece of work”. He referred to the King as “a comedian” after his radio speech to the country that followed a comedy programme.

Perhaps less controversially and probably due to their activities with girls near his home, Jack declared “Yanks” to be “round-shouldered, flat-footed, slouching lot of men, most of them gum-chewers”! He forecast disaster for Britain, her cause being hopeless should Hitler rally the countries of Europe. Not an embittered man, however, Jack relished debating matters with friends and acquaintances, including academics. He was delighted when Labour won the election after the war.

A very kind-hearted man by nature, Jack let 99 Shelford Road during the war to a hard-up young woman for only two guineas a week. He helped a blind masseur study for his exams. He befriended an Italian Prisoner of War, also helping him with exams and once bought bread rolls for some hungry German POWs parked by their guards outside a baker’s shop.

Swimming

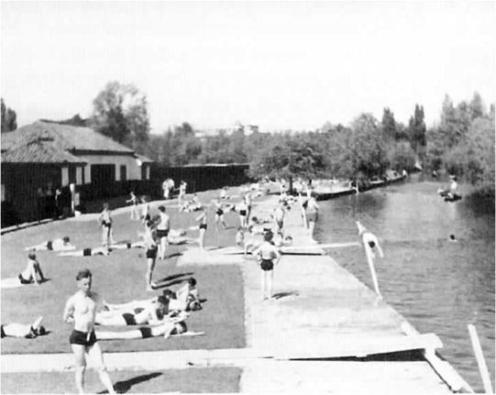

Jack was a dedicated swimmer, becoming the most celebrated river-swimmer in Cambridge. Having entered the water aged one he first swam when he was three and by the age of four was a clever diver. Paramount Sound News could not persuade the shy young Jack to talk when they filmed his prowess. He was later one of the self-styled New Town Water Rats who almost lived at the swimming place on Sheep’s Green in the summer.

He swam all year, rarely missing a day and won the first of many trophies when 19, by then a lean six-footer . In winter, Jack would often break through the ice to take a dip, such was his enthusiasm. Jack founded the successful Granta Swimming Club in 1934. In his unpublished book, Swimming for Fun, written at the suggestion of his friend Neil Bell, he embodied all his experiences with swimming.

Tributes

Following a broadcast in 1967, the Radio Times reported that those who had heard Jack were moved by his determination and fortitude. Listeners wrote to the BBC about his disarming frankness and lack of bitterness which characterized his recollections. Cambridge News journalist, Deryck Harvey, in his profile of Jack, called him “one of the most dynamic and beguiling personalities in Cambridge “being” writer, scholar, philosopher and friend”.

Tailpiece

Let Jack Overhill himself have the last word: he said, “Don’t forget that first and last in life – and it takes precedence over everything – writing, reading, sex and the rest of it – I’m a swimmer right to the marrow in my bones”.