Edmund Brookes

November 2015

Edmund Brookes gave a presentation about the origin of the name ‘Whittington Road’ at the Local History Group meeting on 12 November 2015. Whittington Road is one of a number of streets named after local personalities, in this case Professor Harry Blackmore Whittington FRS (born 24 March 1916, died 20 June 2010).

There is a separate page with information about the derivation of street names.

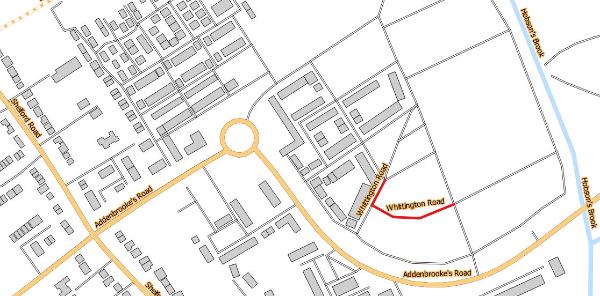

Whittington Road is one of the roads in the Clay Farm development in the south of Trumpington. Part of the Paragon development, it links Cornwell Road, Ellis Road and Whittle Avenue, from the southern corner of the central play area. The homes in Whittington Road were constructed from 2014-15 and occupied from late 2014.

Edmund Brookes wrote that Harry Whittington was a professor at Sydney Sussex College, who Edmund knew personally, and who was a loyal member of Trumpington Church in the latter part of his life, though he had been brought up a Methodist. Edmund knew he was eminent, but until he read his obituary in the Daily Telegraph (8 August 2010), Edmund did not realise how eminent he was. Harry Whittington’s main claim to fame was his discovery that tribolites were the most diversified of all invertebrates during the Cambrian Period, he was also responsible for setting the standard for naming and describing fossils.

Born in Birmingham, Harry Whittington was orphaned at the age of 2, when his gunsmith father died in the 1918 flu epidemic. He was then brought up by his Mother who lived with her parents. Born into a Methodist family, he never lost his religious commitment. Educated at Handsworth Grammar School, Birmingham, and Birmingham University, he graduated with 1st Class honours in 1936. Immediately on graduation, he was granted a research studentship leading to a PhD studying palaeontology in the Berwyn Hills north of Llangollen, and tribolites. He then spent his whole working life (and his long retirement) at a variety of universities, finally coming to Cambridge in 1966 to take up the Woodwardian chair in Geology and a fellowship at Sydney Sussex College which he retained until his retirement in 1983, though he effectively continued working almost until his death in 2010, a further period of 27 years.

From Birmingham, Harry Whittington went to Yale in 1938 on a Commonwealth Fellowship, but a condition of the award was that he had to return home or move to a different part of the British Empire on the outbreak of war. This presented Harry with a problem, as he was a conscientious objector. He chose to take up a lectureship at Rangoon University, Burma, taking his wife Dorothy who he had met in the USA and married in Washington, DC, in 1940. Pearl Harbour and the Japanese advance into Burma then caused them to make a traumatic journey to Chengtu in the Szechuan Province of China, where he and his wife volunteered to work at a medical unit. He was appointed lecturer and subsequently professor at Ginling Women’s College, associated with West China Union University, and supported by the American Baptist Mission. This post enabled him to carry out geological reconnaissance on the Tibetan border. After the War, he was back lecturing at Birmingham in 1945, but in 1949 moved to Harvard as Professor of Palaeontology and curator of vertebrate palaeontology at the Museum of Comparative Zoology. After 17 years, there he moved to Cambridge in 1966 for a further 17 years. Towards the end of his Cambridge tenure, the amalgamation of departments removed – probably thankfully – his administrative workload, enabling him to concentrate on research and teaching.

So much for his career, but what about his work, where his fellowship of the Royal Society demonstrates his eminence. His main area of interest was tribolites, animals with a very hard- carapace, which thrived from the Cambrian period to the Permian, c. 540-250 million years ago. Apparently they were distantly related to horseshoe crabs and lived in the sea and crawled on land. Harry Whittington’s work revolutionised what we know about these creatures. In 1966, just before coming to Cambridge, at the invitation of the Canadian Geological Society, he chaired a commission examining the Burgess Shale deposits in British Columbia, which had been found during the building of the Canadian Pacific Railway in 1909. He made several expeditions to the site and continued his work when he moved to Cambridge. Working in the Sedgwick Museum of Geology, the implications of their discovery were colossal as they indicated that trilobites became victims of a mass extinction. The work concluded that the survival of many species depends more on chance events than on environmental adaption. The theory remains controversial and the full implication of Harry’s work has yet to be established. His work was described as some of the most elegant technical work ever accomplished in palaeontology. Someone said that if there was a Nobel Prize in the subject, Professor Whittington’s team should be the first recipient.

Retirement meant no slackening of his workload and most mornings he was at the Department of Earth Sciences, which had been formed from the combination of the Geology/Geodesy and Minerology/Petrology departments.

But what about Harry the man. He was an exceptionally courteous and very mild mannered person for whom status had no significance. Living in Rutherford Road, he usually went to college most mornings, especially after Dorothy’s death, as early as 6 am. En route to the station, Edmund often saw him driving his Volvo 343 along Trumpington Road to college, to both work and have breakfast! He and Dorothy had no children but they cared for her sisters and their respective children. In later years Dorothy suffered ill health and almost went blind. Without demur he assiduously cared for her until her death in 1997. He took her regularly to church, especially at Evensong.

When the Local History Group and the Residents’ Association were proposing names for streets in the new developments, it seemed very appropriate to include Harry Whittington.