Dr Joanne Sear

April 2025

This paper discusses the importance of the manorial system for the whole of society in the late medieval and early modern periods. It focuses on the history of the various manors in Trumpington and their influence on the lives of ordinary people. It is an extended version of a talk given to the Local History Group on 20 February 2025.

Introduction

In 1066, William of Normandy conquered England. From this date, he strengthened a manorial system that already existed in the country in a rudimentary form and introduced a form of social structure which has since become known as the feudal system and which is closely associated with manors. These actions led to the firm establishment of the land unit known as the manor. For the vast majority of English medieval society, the manor was the most important secular institution which not only controlled peoples’ economic lives, but regulated their behaviour, ordered their social relationships and restricted their personal freedom.

Manors continued in a relatively rigid form from the Norman Conquest until the end of the Middle Ages, so from around 1066 to about 1550, although some aspects continued well beyond this date. The paper will briefly discuss what a manor was and how it operated; discuss the manors of Trumpington during the Middle Ages; and then briefly outline how some of the Trumpington manors changed after the Middle Ages, so from around 1550 onwards.

The Feudal System

To start with a brief overview of the manorial system and its relationship with the social structure known as feudalism. Very basically, feudalism was a state of human society which was formally structured and stratified on the basic of land tenure. All land in England was ultimately owned by the king, and some of this was kept in hand by the king for his personal use. Other land was given by the king to the church, or to nobles and barons who, in return for their landholdings, had to serve on the royal council and provide the king with knights for military service when he demanded it. The nobles kept as much of their land as they wished for their own use, then leased out the rest to their knights in return for the military service when demanded by the king and for protection. All of these landholdings, whether they were held by the king, the church, barons or knights, were held in the form of a unit known as a manor. Those who held manors were known by the title of ‘lord of the manor’ and held complete control over the manor. They could establish their own systems of justice, set their own taxes and, in a few cases, even mint their own money or exact capital punishment. It should be noted that high status men, the king and his nobles, together with many larger ecclesiastical institutions, held a series of manors rather than just the one, and these might be spread around the country rather than concentrated in a particular area. It is also worth noting that the land unit known as a manor was not the same as the land unit referred to as a parish or village, even though they might share the same name. Trumpington is a case in point, because the name ‘Trumpington’ was not only applied to the parish or village of Trumpington, but also to one of its manors. Despite sharing the same name, the parish of Trumpington was not the same as the manor of Trumpington, they had very different boundaries.

The lord of the manor used his, or, very occasionally, her, manor to establish a system whereby he could raise money and other obligations from his land to enable him to live comfortably and also to enable him to meet his obligations to his overlords, including the crown. In order to do this, all lords of the manor relied very heavily on the peasantry, either to work on the manor directly, or to provide rents for land which they held from the manor. Medieval peasants were broadly divided into two types and the Domesday Book of 1086 clearly distinguishes between the two. At the time of the compilation of the Domesday Book, the largest of these two types were villeins or serfs who probably comprised just over 70 per cent of the population. Villeins were an unfree, dependent peasantry who had no rights in common law and who were tied to the manor. In this capacity, they were required to provide a range of payments and services to the lord, known as servile incidents. These came in a wide variety of types and forms, but those that were the most commonly associated with villeinage and unfree status were as follows:

- Week works, unpaid labour services which villeins had to render weekly on the lord’s demesne land. Villeins provided much of the labour for the lord’s land and these week works were often very heavy, frequently two days a week when the peasant had to work for the lord and could not work on his own land;

- Merchet, or the right to marry. If a villein wanted to get married he had to obtain the approval of the lord and pay a fee, usually 1 to 2 shillings;

- Tallage, the lord had the right to tax his villeins at will. If he needed to raise money for whatever reason, he could levy a tax accordingly;

- Leyrwite / chyldwyte, a fine would be levied on the father of a female villein who lost her virginity, committed fornication, or lived with man outside of wedlock (leyrwite), or if she had a child outside of wedlock (chyldwyte);

- Chevage, if a villein wanted to live outside the manor, he had to obtain the permission of his manorial lord and pay a fine;

- Heriot, on the death of a villein, the lord of the manor had the right to seize his most valuable possession, which was usually his best beast, but could be another chattel;

- Millsuit, if the lord owned a mill, he could require his villeins to grind their corn at his mill and they would be expected to pay for the service, either with money or with a proportion of their ground corn.

There were others, these were the main ones and exercised by most manors. It was this system, by which the lord of the manor could force his dependent peasants to work his land and be subject to these other obligations, in return for his protection and justice, which was the condition of bondage which became known as serfdom.

The other group of medieval peasants were freemen, who comprised about 14 per cent of the population at the time of Domesday. Freemen did have rights and they were not obligated to provide many of the seigneurial dues which villeins were required to perform.

The Manor

So, at its most basic level the manor was a unit of land which usually enshrined an agricultural community and which the holder, the lord of the manor, could use to provide for the needs of his household. How did this work in practice?

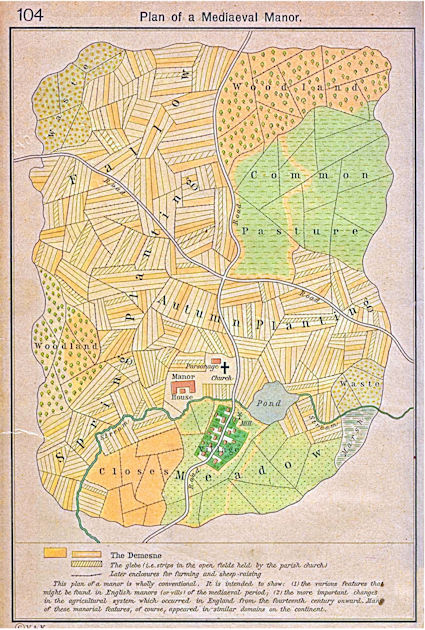

Figure 1 is a plan of what is now known as a classical medieval manor. It conveys the basic theory behind how a manor operated, but it is worth stressing that as manors were largely autonomous units, in practice most manors had adapted to meet their individual needs and so often varied a bit from this standard pattern, so please do not assume that all manors conformed strictly to this. A classical medieval manor generally consisted of a manor house, usually near the church, and a parsonage or rectory. This particular manor also held three large fields, one for spring planting, one for autumn planting and one left fallow, with the fields rotated each year to replenish the nutrients in the soil (again, just to make the point that the three field system was not operated by all manors, some had less than three fields, and some had more). In addition, a manor usually included some land for pasturing animals, meadow for providing hay for overwintering animals, some woodland for supplying timber and firewood and might include a pond or river to provide freshwater fish, and a mill. Some land within the manor might also be unsuitable for husbandry, for whatever reason, and would be designated as wasteland. In this instance, the manor also includes a relatively nucleated village.

It is apparent that the three fields are all subdivided into small strips which have different colours or shading on the plan. Some is shaded yellow, some is cream, and some is shaded with diagonal shading. Manorial land was of three types:

- the land with the diagonal shading was glebe land which was held by the parish church and which supported the parish priest;

- the land shaded in cream was what was known as demesne land. Demesne land was the land set aside for the lord of the manor, it was kept in hand and not leased out. The produce from this land was used directly to provide for the needs of the lord and his household. It typically comprised around 40 per cent of the land in the manor although this varied widely by manor and also by time period;

- the land shaded in yellow was the land which the lord of the manor leased out to his tenants.

It was this leased-out land which the lord of the manor used to raise money and other obligations. This land was of two types, generally known as unfree or customary land, and land held by free tenure. It is worth noting that the unfree or customary land had many of the servile incidents previously referred to attached to it. So, if a freeman held customary land, he was still obligated to provide the servile incidents due to the manorial lord in addition to any monetary rent that he owed for the land itself. By contrast, land held by free tenure did not have customs attached to it. The lessee paid a rent for the land and that was it. There were no other obligations attached. So, a medieval peasant could be personally free or unfree, and any landholdings could be free or unfree. The only way that a medieval peasant was not obligated to the lord was if he or she was of free personal status, i.e. a freeman or woman, and held only free land.

Sources for Manors

Generally speaking, there are very few written sources before the thirteenth century, but there is one exceptional source for medieval manors in the form of the Domesday Book, compiled in 1086. The Domesday Book was, basically, a record of who was holding what manors in England and what they had on their manors in terms of assets.

The other main source for manors comes directly from the manors themselves. The administration of manors increasingly required the production of what are known as ‘manorial records’. Their survival is very ad hoc, but large numbers have survived.

Very briefly, manorial records broadly fall into three categories:

- Manorial surveys, extents and rentals. These are basically ‘mini Domesdays’, as they are an assessment of the assets in the manor. A number of these have survived for the Trumpington manor for the late medieval period;

- Manorial accounts. Annual accounts of the income and expenditure of the manor were produced which relate to the day-to-day running of the manor as a fiscal unit. These give a lot of information about the practical workings of the manor – how many fields, what crops were grown, what animals were kept, etc. Manorial accounts have survived for De la Poles manor;

- Manor and leet courts. The lord of the manor was permitted to establish his own judicial system which administered justice in the manor through manorial courts. These were broadly of two main types:

- general courts, which every lord of the manor had the right to hold on his manor and which largely dealt with aspects relating to the administration of the manor such as land transfers, trespass, etc. Rolls relating to the general court have survived for De la Poles manor;

- some manors also held a second court which was known as the court leet or the view of frankpledge. This was a petty criminal court which was the lowest court of law in England during the Middle Ages. Rolls relating to the court leet have survived for Trumpington and De la Poles manor;

- some other types of court did exist, such as market and fair courts, but they were really just variants of the first type, the general court, and none of these appear to have been held in the parish of Trumpington.

Trumpington Manors

Some of the evidence for the Trumpington manors is a little contradictory, so what follows is a best case scenario, but might not be spot on. I would also add that this is ‘work in progress’, so some of the details may be revised at a later date as more evidence emerges. It should also be noted that no maps exist for these medieval manors, so it is impossible to be precise about boundaries and extents, but the sources do give a few clues which enable some conclusions to be drawn.

It is possible to identify that at least seven manors existed in Trumpington at one time or another during the medieval period. The following names will be used to identify these manors:

De la Poles

Trumpington

Beaufoes

Arnolds

Tincotes

Land of Countess Judith

Radegunds

However, as manors were often named after the manorial lord who held them, and some of these passed through a number of different families, De la Poles and Beaufoes were both also known by other names at various times.

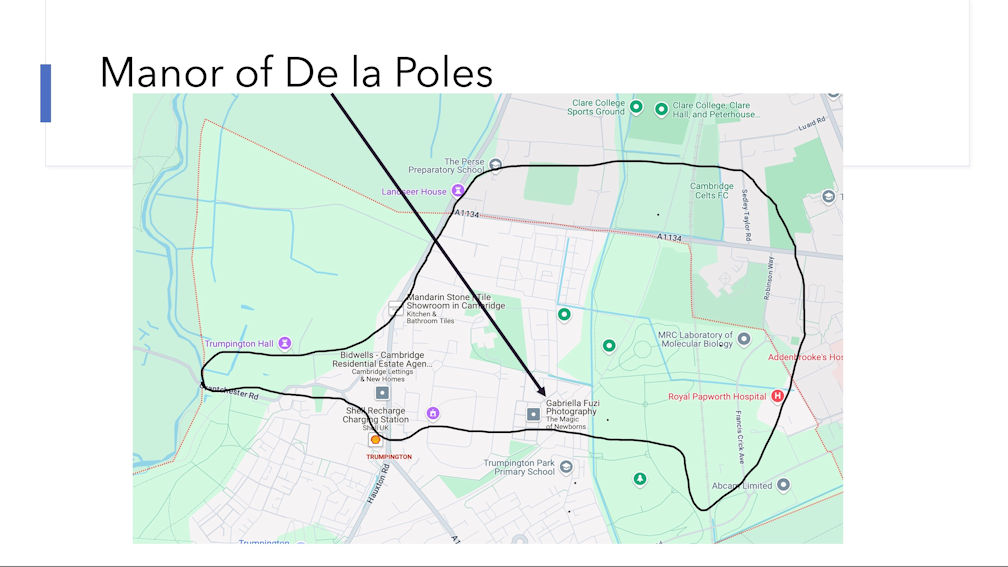

De la Poles / Caleys

The Domesday Book refers to six manors existing in Trumpington. The chief and largest of these was the manor which eventually became De la Poles, although at the time of Domesday, the manor was held by William de Cailli, so that it was also known for some time as Caley’s manor. At the time of Domesday, De la Poles was around 500–600 acres and contained a population of about 70. It also contained a mill and from this reference and others contained in the manorial documents themselves, it would seem that De la Poles stretched from the river in the west of Trumpington right across the present-day Trumpington High Street and to Nine Wells in the east. It also included the church, although probably did not extend much further south than the church, and to the north it included a manor house which was in all likelihood between the present Trumpington Hall and the church.

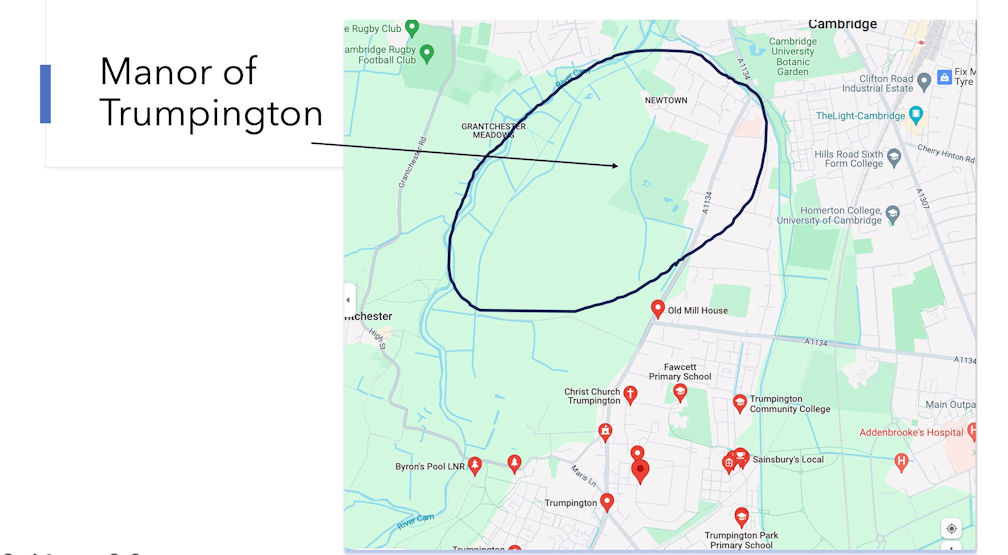

Trumpington

The next largest manor was that which became known as Trumpington manor. At the time of Domesday, it was held by Robert, son of Fafiston, about whom very little is known. It was around 360 acres at the time of Domesday and contained a population of around 50. Again, from references in various sources, it is possible to identify that this manor lay to the west of the parish and stretched from the river in the west to the present-day Hills Road to the east. It probably did not extend as far as the church to the south, but extended much further north than De la Poles manor, taking in the area that is now Chaucer Road, Latham Road and Newtown. At a later date, it also included a manor house, which over the years and with much rebuilding and renovation eventually became Trumpington Hall.

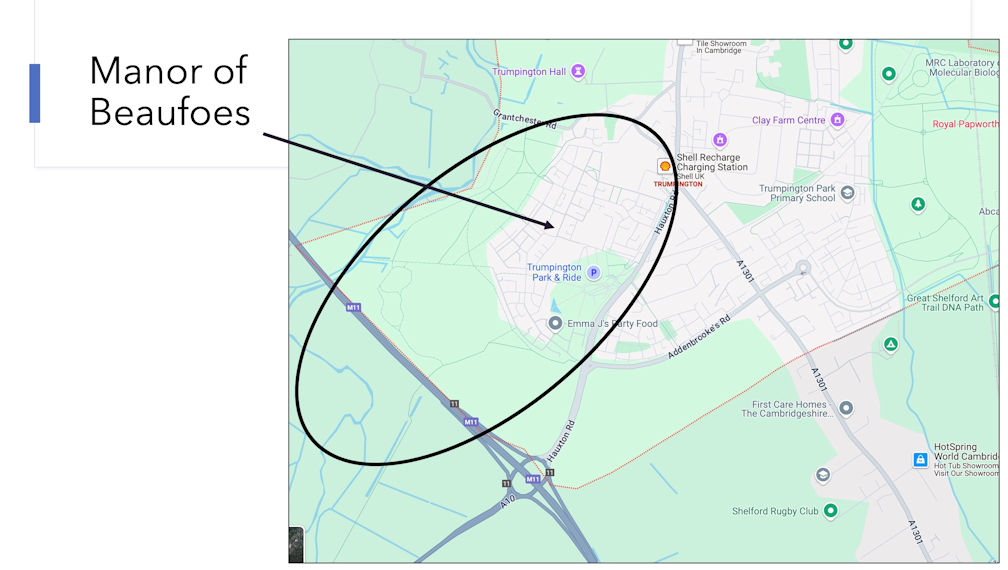

Beaufoes / Peverels / Crouchmans / Huntingdons / Bowyers / Anstey

Then came two manors which were of a roughly similar size. The first of these was Beaufoes. At the time of Domesday, Beaufoes held around 300 acres of arable and some meadow and had an approximate population of 40. At the time of Domesday, Beaufoes was the land of Picot, High Sheriff of Cambridge, who had a notoriously bad reputation in Cambridge. Picot had probably come over to England with William the Conqueror, and was responsible for the building of Cambridge Castle and St Giles’ church. His service to William was rewarded by the gift of numerous manors, particularly in this area of the country. Unfortunately, his son and heir, Robert, was not so successful, he was implicated in a conspiracy against Henry I and fled the country. His estates were forfeit, including Beaufoes manor, which subsequently passed through a number of different families, hence the fact that it was known by various names. However, we can place its location with some certainty, since it eventually became the manor of the Anstey family. The manor house of the Beaufoes manor lay on the northern edge of the manor and was rebuilt by the Anstey family as Anstey Hall. The manor was focused on the hall and stretched south and west to include the area which is now Trumpington Meadows nature reserve and housing development, as well as the Park and Ride site.

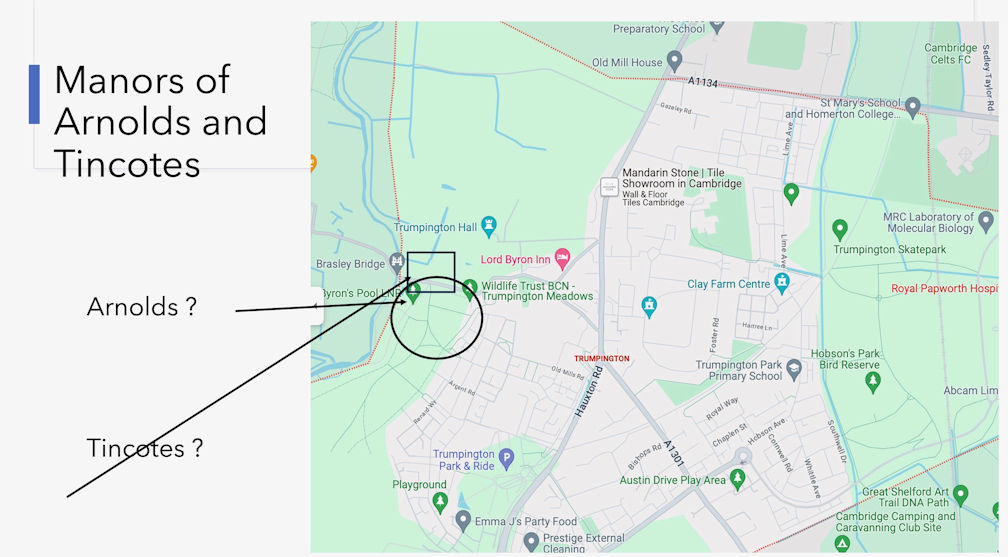

Arnolds / Tincotes

The second of these smaller manors was a manor which was held by Ernulf de Arnulf from Count Eustace of Boulogne at the time of Domesday. However, although this was a single manor in 1086, it subsequently became divided into two separate manors, known as Arnolds and Tincotes. At the time of Domesday, the joint manor was around 300 acres and held a population of about 20 people who were almost all serfs working for the manorial lord. The location of Arnolds and Tincotes manors are rather more speculative than those previously mentioned. Arnolds manor was to the south of De la Poles and between it and Beaufoes, whilst Tincotes possibly lay near to Arnolds manor.

Land of Countess Judith

There is a final manor referred to in Domesday which is simply identified as the land of Countess Judith, although it was held by Godlamb as manorial lord. Countess Judith, or Judith of Lens, was the niece of William the Conqueror and held huge estates across the Midlands and East Anglia. However, we know very little about her manor in Trumpington other than it was very small, only about 60 acres, with no mention of anyone living on the manor, or other assets. This manor subsequently disappears from the records and it is impossible to ascertain where it was, or what ultimately happened to the land.

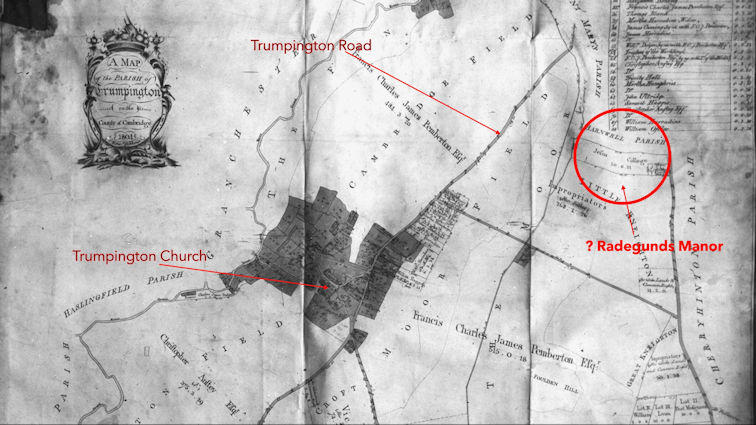

Radegund’s Manor

To the list of Domesday manors must be added one other known manor, known as Radegund’s manor. In 1166 Ralph de Cailli, of Cailly’s manor, later De la Poles, gave 15 acres of his land to the nuns of St Radegund’s in Cambridge. Other gifts increased this land to 32 acres before the land was passed to Jesus College at its foundation in 1496. For a number of reasons, it seems likely that this manor was in the north-east of Trumpington parish, not least because at the time of enclosure in 1804, the enclosure settlement gave Jesus College 20 acres in the north-east corner of the parish, which was probably a reflection of the earlier manor.

Other Manors

It does seem likely that other, much smaller manors may have operated at some time or another within the parish, but these, if they did even exist, have disappeared from the records.

Trumpington Manorial Records

Some manorial records do still exist for the Trumpington manors although there is not a lot for the medieval period, only for De la Poles and Trumpington manors and these predominantly date from the end of the medieval period, so from the mid-1300s onwards. These records show that these manors were, unsurprisingly, mainly focused on agriculture. A range of grain crops were grown, including barley and wheat. Two mixed grains were also grown; maslin, which was usually a mix of wheat and winter barley, and drage, a combination of spring barley and oats. These mixed grains were very popular in the Middle Ages since they were more resilient to crop failure at a time when this could lead to mass starvation. If one of the grains did not grow well in a particular year, for whatever reason, there was a chance that the other grain might be more resilient. The other crop that was grown in abundance was legumes and particularly peas. Legumes formed an essential part of the medieval diet at a time when far, far less meat was eaten than today, and it was also good for the soil and an important fodder crop.

A few more unusual crops were also grown. Peppercorns were both grown and sold by the manor and also occasionally received in rents from tenants. The use of peppercorns for paying rent was very widespread in the Middle Ages and has, of course, passed into popular parlance with the term ‘peppercorn rent’ still used to denote a low or nominal rent. And nettles were also grown on the manor and sold. Nettles had a wide range of medicinal and culinary purposes, although in this instance, they were probably used to make rope. Finally, saffron was also grown. As it is today. saffron was the most expensive spice at this time, particularly as much of it was imported. However, it was cultivated in England, particularly in this region. Obviously, it is largely associated with Saffron Walden, but it likes light, well-drained and chalk-based soils which meant that areas of Trumpington suited its cultivation.

The manorial records also show that a wide range of animals and fowl were kept on the manors. Horses, unsurprisingly, were kept for pulling the ploughs and carts required for agriculture. Sheep were kept for both wool and meat; cows for milk and meat; pigs for meat; and chicken and geese for eggs and meat. A few more unusual animals were kept on the De la Pole manor, almost certainly for consumption by the manorial lord since these were high end foodstuffs: boars were kept, which were probably for consumption during major feasts including Christmas; and doves, again, were almost certainly reserved for consumption by the manorial lord and probably associated with feasting.

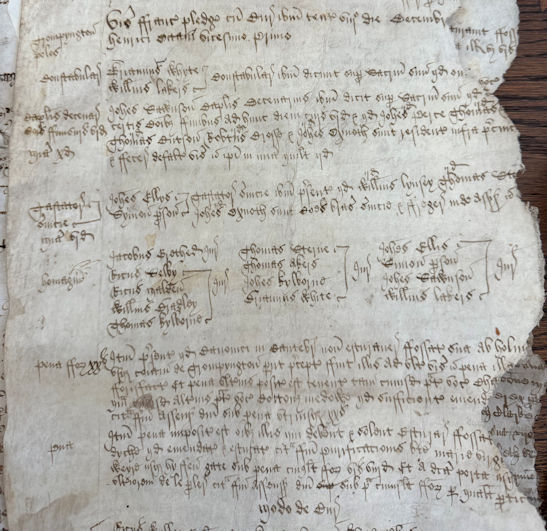

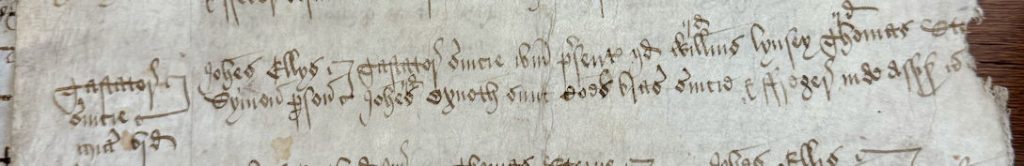

However, the manors were not only associated with agriculture, as is demonstrated by the records of the court leet (also known as the view of frankpledge). Not all manors were entitled to hold the view of frankpledge, but three of the Trumpington manors, De la Poles, Trumpington and Beaufoes, did. This was a petty criminal court which was the lowest court of law in England during the Middle Ages, but which was essential to the maintenance of law and order within the manor and consequently within the country. Cases which could be tried at the court leet varied, but they mainly heard mundane breaches of the peace, trading offences and poaching. And the way in which this was managed was through tithing groups. The basic idea was every male on the manor over the age of twelve was in a tithing group, usually consisting of ten men. Together, these men were responsible for policing the behaviour of everyone in the group. If a misdemeanor was committed, the head of the tithing was expected to present the offence and the perpetrator at the court and if he could not or did not, all the men of the tithing could be fined. The court leet rolls would report the names of the heads of these tithing groups, and Figure 7 shows the top of a court leet roll with view of frankpledge from the manor of De la Poles in which the names of the thirteen men who headed up the tithing groups can be seen, listed in three columns. These men would be expected to pay homage to the manorial lord on behalf of their tithing group, to report any misdemeanors that had been committed by members of their tithing group, and then to act as a member of a jury in relation to these offences.

The rolls from the court leet usually make for quite interesting reading with a range of minor breaches of the peace including fights, raising the hue and cry and other squabbles. Those from the Trumpington manors are a little disappointing in that respect. However, the following examples give a flavour of the sort of issues that the court leet dealt with. In 1573, Richard Howe was fined a quite sizeable amount, 3s 4d, for making affray with the wife of Alexander Kynge and drawing blood. There was evidently a fair amount of brewing happening in the manor. Brewers had to pay for a form of licence to brew ale and at least three brewers pay in each court to cover their brewing activities (Figure 8). This entry is in Latin, but translates as ‘Aletasters, fines 6d. (in the margin). John Ellys and Simon Parson, aletasters there, present that William Lynsey (fined 2d), Thomas St ? (fined 2d) and John Exnoth (fined 2d) are common brewers of ale and have broken the assize. Therefore they are fined’. The rolls also record a number of offences relating to impediments being placed in various watercourses across the village, including the body of water which became Hobson’s Conduit. The offences and fines relating to these misdemeanors are a reflection of how important a clean and reliable water supply was to Trumpington’s residents.

There may have been a further area where the Trumpington manors were not simply concerned with agriculture. It is recorded that in 1314 Edward II granted a charter to Giles de Trumpeton, lord of the manor of Trumpington, authorising him to hold a three day fair on his manor around the 1st of August. Unfortunately, there is no firm evidence that this fair ever came into being and many of these charters were purely speculative. However, given the location of the Trumpington manor, and the fact that medieval fairs were almost always held close to a river, it seems likely that any fair that did take place was held on the Trumpington side of the river Cam opposite Grantchester Meadows. A fair was being held in Trumpington on 1st August as late as 1805, but no details have survived about its location and, in any case, there is no evidence that it was a continuation of the earlier fair.

Lords of the manor

Given the number of Trumpington manors and their longevity, there were, inevitably, quite a few ‘lords of the manor’ over the years, but two in particular have not only left their mark on Trumpington history, but were also active on a wider stage.

Sir Roger de Trumpington

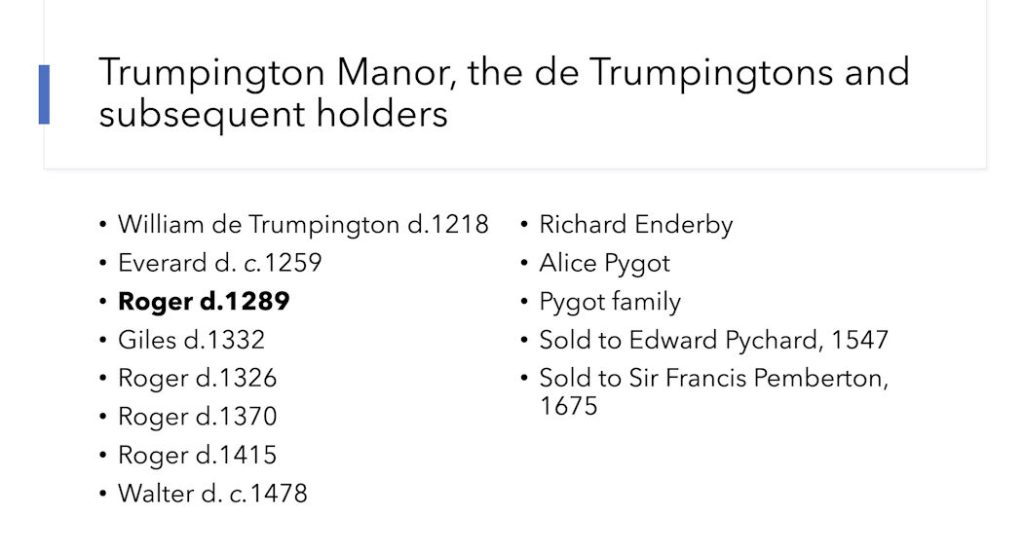

The first one of these is Sir Roger de Trumpington who held the manor of Trumpington and who still appears on our on our village sign, together with the de Trumpington coat of arms (Figure 9). The de Trumpington family did not hold the Trumpington manor at Domesday, however, it was in the hands of the family from at least the beginning of the thirteenth century when it was recorded as being held by William de Trumpington (Figure 10) and it stayed in the family, albeit that female heirs led to a change of name, until it was sold to Edward Pychard in 1547. So, the de Trumpington family held it for around three hundred years.

Sir Roger was the third de Trumpington known to have held the manor and he inherited it on the death of his father Everard around 1259. However, Sir Roger cannot have spent much time in Trumpington during his early years as lord of the manor. He fought on the side of king Henry III in the civil war known as the Second Barons’ War which culminated in the Battle of Evesham in 1265. At the Battle of Evesham, the king’s forces were led by the king’s son, the future Edward I, and after Edward had extinguished the rebellion, he left to join the Ninth Crusade to the Holy Land in 1270. Sir Roger de Trumpington had evidently become close to Prince Edward, and travelled on crusade with him. Unfortunately, the crusaders had limited success, so the decision was taken quite early on to return home.

Some eight years later, Sir Roger is recorded as one of 38 knights taking part in a tournament at Windsor, but he then disappears from the records until his death in 1289. On his death, he was buried in Trumpington church. However, although the commemorative brass in the church on the chest-tomb between the north chapel and north aisle was once thought to belong to Sir Roger, that is no longer the case (Figure 11). It may have been prepared for Roger, but was almost certainly reappropriated for his son Giles, who died early in the fourteenth century. Whoever the effigy actually depicts, it is quite striking; the figure is depicted in typical armour of the time, with a surcoat and broadsword and chainmail extending from his head to his feet. The Trumpington family arms are depicted on his sword, shield and ailettes (behind his shoulders) and his head rests on his helmet, which is chained to his waist.

Edmund de la Pole

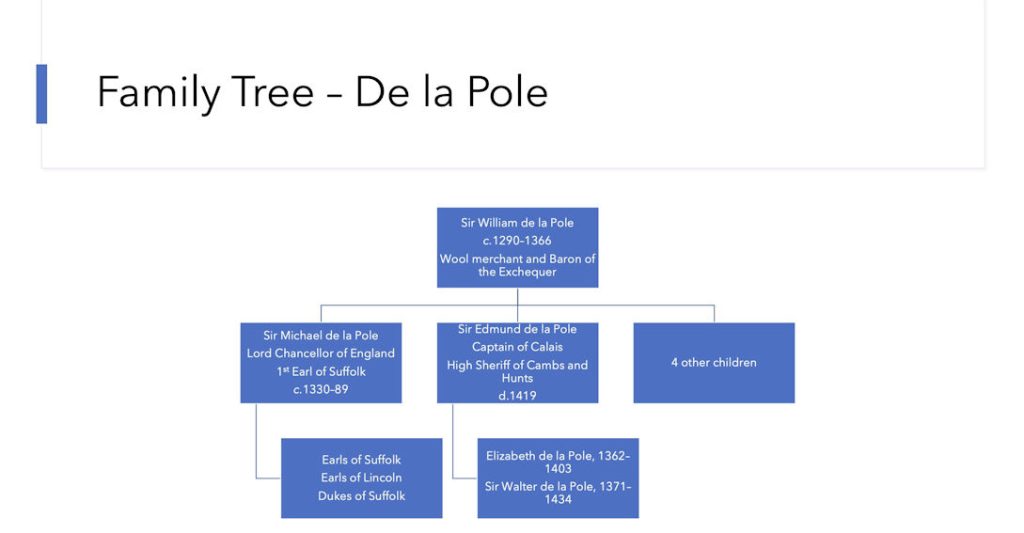

The second significant lord of the manor was Sir Edmund de la Pole, lord of the manor of De la Poles between 1372 and 1419. In the Middle Ages, it was rare for anyone to rise much above the status to which they had been born. There are very few exceptions to this, but one family who did manage to achieve this was the de la Pole family. The rise began with the father of our Edmund, William de la Pole. William’s origins are relatively obscure, but he became a wealthy wool merchant at the time when huge amounts of highly prized English wool was being exported to the Continent. He became a royal moneylender and Chief Baron of the Exchequer and his significance was such that a statue was erected to him in the nineteenth century in his home town of Hull. William’s descendants played a huge role in English history for around a century and a half. They became earls of Lincoln and Suffolk, and later dukes of Suffolk, and married into the royal family, with John de la Pole being designated as Richard III’s heir. They also played a significant role in the Wars of the Roses although, unfortunately, ultimately on the wrong side!

However, the earls and dukes were descended from the first son of William de la Pole (Figure 12). Our de la Pole, Edmund, was a younger son and although he did not achieve the status of his elder brother, his military and government achievements were still significant. In his early career he engaged in military service overseas, particularly in France, until being elected to Parliament for the first time in 1376. Following on from this, he was in the prestigious post of captain of Calais from 1384 to 1388. Back in England, he served as one of the special justices appointed to deal with the rebels after the Peasant’s Revolt of 1388, perhaps appointed by his elder brother Sir Michael de la Pole, who was by this time Lord Chancellor of England. Edmund subsequently served as High Sheriff of Cambridgeshire and Huntingdonshire before returning to his parliamentary career.

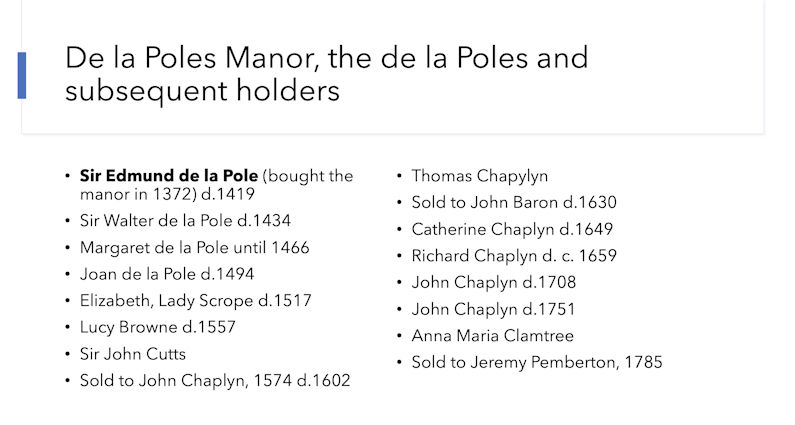

Edmund bought the manor in Trumpington in 1372, although he held a significant number of other manors across the country including Dernford manor in nearby Sawston. Evidence confirms that he spent time on his manor in Trumpington; he had the manor house substantially rebuilt and had an oratory licensed there in 1376. However, although Edmund held huge estates in his own name, through his first wife, Elizabeth, the manor of Boarstall in Buckinghamshire came into his hands which included a fortified manor house. Although much of the house has now been demolished, the gatehouse still stands and is in the possession of the National Trust. When Edmund died in 1419, he was at Boarstall rather than Trumpington. His manor of Trumpington passed into the hands of his son, Walter (Figure 13). Although the manor stayed in the family for some years, it largely descended through the female line.

Post Middle Ages

The manorial system flourished for at least five hundred years, from the Norman Conquest to the end of the Middle Ages, although evidence suggests that it was starting to unravel by the end of the thirteenth century. One of the reasons for this was that tenants were particularly reluctant to take over landholdings which had the servile dues attached to them. Increasingly, this dislike of servile incidents meant that land tenure was based simply on the payment of a rent for a landholding without any other strings attached. As has been noted, one of the servile dues was week works, labour services for the lord on the demesne land. As landlords found themselves increasingly unable to secure tenants prepared to accept week works, they initially turned to waged labour to work their demesne holdings, but by the end of the Middle Ages this was no longer a cost-effective option. For many landlords this left them with no alternative but to lease out their demesne holdings and this led to a significant unravelling of the manorial system. Increasingly, land was freely available and relatively cheap to rent and many men actively accumulated increasingly larger landholdings and began to farm for a profit rather than just subsistence, the beginning of what later became known as agrarian capitalism. The former terms used to describe the peasantry, such as villeins and serfs, disappeared and from the fifteenth century, terms such as gentlemen or gentry, yeomen and husbandmen were increasingly used to describe men who held larger landholdings and who were often ‘farming’ the land of manorial landlords, with the word ‘farm’ deriving from these arrangements and originally denoting an amount payable as rent.

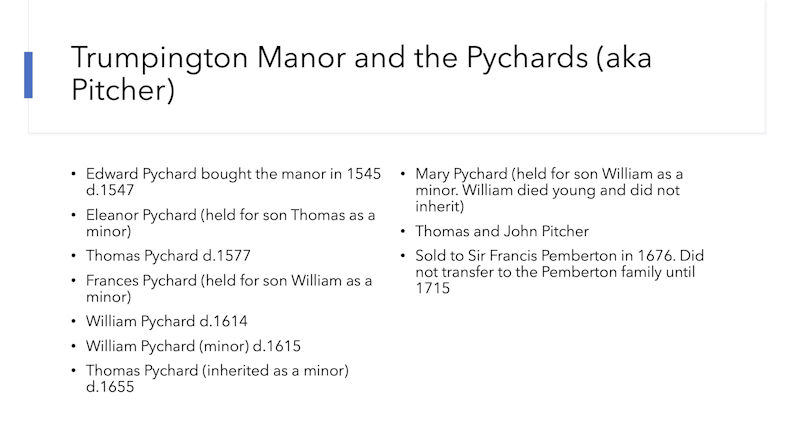

Two families did just that in post-medieval Trumpington and redefined Trumpington landholdings. The first of these families was the Pychard or Pitcher family. The Pychards probably came originally from Bottisham to the north of Cambridge, but they were renting land on at least one of the Trumpington manors since 1400. The family were evidently upwardly mobile and men from the family increasingly styled themselves as ‘gentleman’. Pychard wills from this period refer to landholdings across Cambridge and the wider county. The family continued to live and prosper in Trumpington, but they were keen to develop estates in their own possession rather than farm land held from landlords. So although the family had been farming land in Trumpington for some time, in 1545 Edward Pychard acquired Trumpington manor from the descendants of the de Trumpington family that we met earlier (see Figure 10). Then, in 1606, William Pychard bought Tincotes manor, so the Pychards were evidently enlarging their Trumpington estates. Unfortunately, the family went through a period where the head of the family died young and left a minority heir (Figure 14). Finally, by 1676, there were no immediate male descendants. The two men who inherited the Pychard lands, Thomas and John Pitcher, possibly had no association with Trumpington since they decided to sell the Trumpington estate and the Pychard association with Trumpington came to an end.

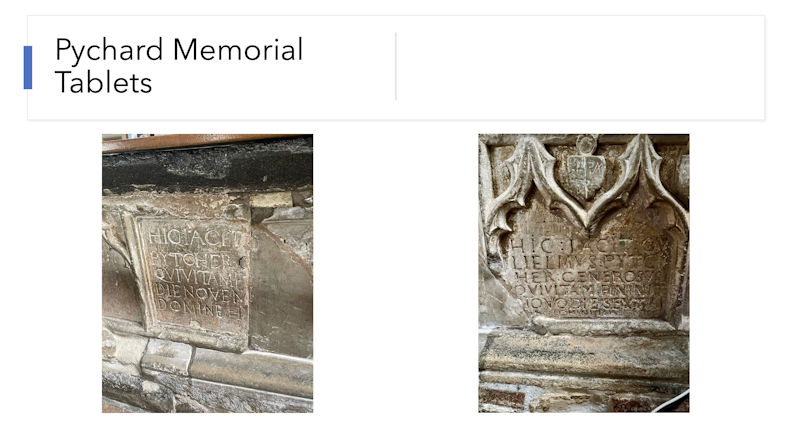

However, a handful of reminders of the Pychards in Trumpington do remain. Firstly, two post-medieval memorial tablets still exist in the parish church on the side of the tomb chest with Sir Roger de Trumpington’s brass on top referred to earlier (Figure 15). One is for Thomas Pytcher, who died in 1577, and the other for William Pytcher, who died in 1614. Secondly, the Pychard family were largely responsible for the creation of Trumpington Hall. Although an earlier manor house existed on the site, and there had been significant subsequent renovations and developments, much of the present-day hall largely dates to c.1600 and a building project undertaken by the Pychards. The existing plan of the house dates back to the Pychard rebuilding, whilst seventeeth-century panelling survives, together with a carved wooden fireplace which bears the Pychard arms. Finally, Pychard Road on the Clay Farm development was named after the Pychard family and a reminder of their long involvement with Trumpington.

The other family that should be mentioned in connection with Trumpington manors and the development of large estates is, perhaps unsurprisingly, the Pemberton family. The two largest Trumpington manors, De la Poles and Trumpington, both ended up being purchased by Pembertons (see Figures 13 and 14). The estates that the Pychard family had acquired came into the possession of Sir Francis Pemberton in 1676; and De la Poles was sold to Jeremy Pemberton in 1785. These manors formed the basis of what eventually became Trumpington Estates, owned by the Pemberton family, which, obviously, is still alive and thriving and which today includes land in Barton, Haslingfield and Grantchester as well as Trumpington. The Pembertons continue to play a significant role in our community and there is some detailed information on this website about the family and their involvement with Trumpington.

Manors did not disappear at the end of the medieval period. Although the role of the manor was much reduced, many manors continued to function in various forms. Many of the field systems established within manors, for example, continued in existence until enclosure, whilst some other aspects continued until the 1920s. Manors certainly did not go away entirely.