Edited by Andrew Roberts

1000 years in Trumpington’s history: Late Iron Age, Romano-British and Anglo-Saxon settlement and the naming of the village. One of a series of pages with Trumpington’s timeline.

30-70 AD, Late Iron Age

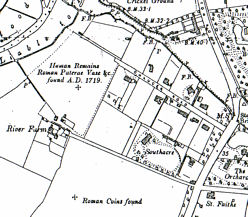

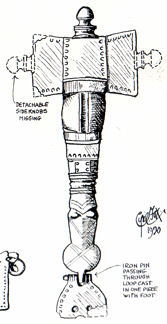

A bronze jug and bowl (patera) were discovered in the north of Trumpington in 1709 and are now on display in the Fitzwilliam Museum.

The patera has a central medallion of an eagle bringing down a deer, then a frieze and decoration, with a separate handle with a ram’s head decoration. They have been identified in recent years as being among a group of items found in 1709; other items included pots, an amphora and the remains of a rectangular folding gaming board. The items date from c. 30-70 AD, the pots with known potter’s marks. They were described in the 1722 and 1806 editions of Camden’s Britannia as being found by labourers working at Dam Hill, to the west of Trumpington Road (said to be on the right side of the road coming out of Cambridge, about ¼ mile from the milestone not far from the river). They are typical of items found in Iron Age burials on the edge of the Roman Empire at the time of the Roman conquest of Britain. These were elite and conspicuous burials of the Romanised or soon-to-be Romanised elite, in areas separate from the main cemeteries. There are comparable burials at Bartlow Hills and Wheathampstead. The finds appear to have been given to Trinity College by a son of James Thompson (Anstey Hall), owner of the land.

Sources of information: Dr Lucilla Burn, Camden’s Britannia and Roman Finds from Trumpington, Fitzwilliam Museum, 3 November 2010. Finds in the Greek & Roman Gallery, case 12 [seen 3 November 2010], Loan Ant. 36, 37, 38 (lent by Trinity College). Babington, Charles Cardale (1883). Ancient Cambridgeshire, or an Attempt to Trace Roman and Other Ancient Roads That Passed Through the County of Cambridge . : George Bell & Sons. Page 48. Fox, Cyril (1923). The Archaeology of the Cambridge Region. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Page 205.

1st-5th centuries, Romano-British

Roman invasion in 43 AD and advance across England from the south east. A substantial part of the country was formally surrendered to Rome in the late summer of 43 AD in a ceremony at Camulodumum (Colchester). The south Cambridgeshire area had probably been under Catuvellauni control up to this time.

There was an early Roman military base at Great Chesterford and a wooden then walled settlement at Cambridge. This was to the north of the river, the basis for a small town rather than a major military centre.

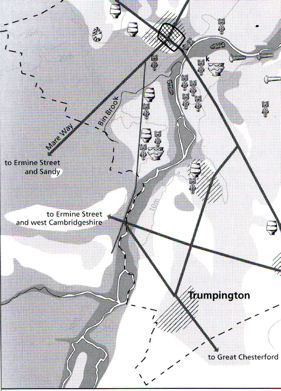

There was a network of Roman roads in the Trumpington area. One road, later called Via Devana, ran along the eastern side of the area (from Cambridge to Red Cross to the east of the current Hills Road, between the ‘fens’ of Trumpington/Shelford and Cherry Hinton): this was part of a major route from Colchester through Cambridge to Godmanchester where it linked with Ermine Street. A second road ran east-west from Red Cross to Grantchester. Writing in 1808, Lysons and Lysons describe this as crossing the great London road just to the north of the village of Trumpington (Babington repeats this in 1888). In 2008, Christopher Evans plotted the road line further north, running from the Addenbrooke’s Hospital area towards Dam Hill, crossing the current north-south road a short distance north of the Long Road/Trumpington Road junction and possibly continuing to a ford between Grantchester and Newnham. A third road may have run south-north from Great Chesterford/Stump Cross to Cambridge, this may be pre-Roman. The southwest-north route from Ermine Street (Royston) to Trumpington and Cambridge may also be pre-Roman. As in the prehistoric period, the line of these routes through the village towards Cambridge was probably to the west of the current main road, along the slight ridge from the area of Trumpington Hall to Vicar’s Brook and the Leys School.

There were Romano-British settlement sites in the Trumpington area, including along the east side of the river to the south west of the current village; pockets of settlement further to the east including in the Clay Farm area; a Roman villa near Nine Wells; and the continued use of the cemetery at Dam Hill in the north of the parish. In his thesis on the Cambridge region published in 1923, Cyril Fox refers to finds of pottery (terra sigillata) from Chaucer Road, including fine platters by named potters found at Upwater Lodge (23 Chaucer Road), part of the important Dam Hill cemetery area (see above). Many of the finds from the sites discovered in the 18th and 19th centuries are held in the Museum of Archaeology & Anthropology and the Fitzwilliam Museum. The Clay Farm excavation in 2010 identified pits, a pottery kiln and a possible funerary monument. The Hutchison site excavation in 2002-03 established substantive evidence of Late Iron Age/Early Roman use of that area, with mixed farming and pottery kilns.

Sources of information: Archaeology reports and visits to archaeological sites. Babington, Charles Cardale (1883). Ancient Cambridgeshire, or an Attempt to Trace Roman and Other Ancient Roads That Passed Through the County of Cambridge. : George Bell & Sons. Pages 29 and 43-51. Evans, Christopher, with Duncan Mackay and Leo Webley (2008). Borderlands. The Archaeology of the Addenbrooke’s Environs, South Cambridge. Cambridge: Cambridge Archaeological Unit. Including page 19, Roman roads; pages 123-39, summary of Hutchison site; page 132, map of Roman roads; pages 141 and 151, maps of archaeological sites and cropmarks. Fox, Cyril (1923). The Archaeology of the Cambridge Region. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Pages 150-52, 167-221. Kirby, Tony and Oosthuizen, Susan (eds.) (2000). An Atlas of Cambridgeshire and Huntingdonshire History. Cambridge: Anglia Polytechnic University. Map 14. Lysons, Daniel and Lysons, Samuel (1808). Magna Britannia. Cambridgeshire. Republished 1978. Wakefield: EP Publishing. Pages 44-45. Taylor, Alison (1999). Cambridge: the Hidden History. Map on page 24; pages 25-38, 41. The Victoria History of the Counties of England (1948). The History of the County of Cambridge & the Isle of Ely. Volume II. Page 48. The Victoria History of the Counties of England (1978). The History of the County of Cambridge & the Isle of Ely. Volume VII: Roman Cambridgeshire. Pages 1-3, 16-21, 28, 46.

Local History Group web page: Clay Farm Archaeology, August 2010.

Early 5th century

Withdrawal of the Roman legions from Britain: Rome was attacked by the Goths in 410AD and Emperor Honorius may have indicated that Britons should organise their own defences.

Sources of information: Dr Sam Newton, Cambridge and the Kingdom of East Anglia, Institute of Continuing Education, University of Cambridge, November 2009.

5th-8th centuries

Angles and Saxons from northern Germany took land from the native British people in southeast England and an Anglo-Saxon culture developed alongside the Romano-British culture, with the growth of small kingdoms. The Old English language was close to Germanic roots.

East Anglia was settled by the Angles, with the development of scattered rural communities. The River Cam was a frontier between East Anglia and Mercia. Cambridge continued as an Anglo-Saxon settlement and port, with the River Cam providing a major route into Britain.

The important Iron Age/Roman cemetery at Dam Hill continued in use (the area between Latham Road, River Farm, and Chaucer Road). Cyril Fox refers to this as an inhumation cemetery in the Anglo-Saxon period, with finds including a spearhead, clasps and brooches (see figures).

Sources of information: Evolving English: One Language, Many Voices, exhibition at the British Library, 2010-11. Medieval London gallery, Museum of London. Fox, Cyril (1923). The Archaeology of the Cambridge Region. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Pages 227, 249. Oosthuizen, Susan (1996). Cambridgeshire from the Air. Stroud: Alan Sutton Publishing. Page 25. Taylor, Alison (1999). Cambridge: the Hidden History. Pages 39-50. The Victoria History of the Counties of England (1938). The History of the County of Cambridge & the Isle of Ely, Volume I . Page 316-17. The Victoria History of the Counties of England (1982). A History of Cambridgeshire and the Isle of Ely, Volume VIII. Armingford and Thriplow Hundreds. Trumpington, page 248.

Mid-late 7th century

There is evidence of the development of the Anglo-Saxon settlement in Trumpington, to the south of the current church. The area was excavated in 2011 in advance of house construction on the Trumpington Meadows site. It included a number of sunken buildings ( ‘grubenhause’) and four burial pits. The national significant finds included a bed burial with the body of a young girl wearing a gold cross (announced in March 2012).

Sources of information: University of Cambridge press release.

Local History Group web pages: Trumpington Meadows archaeological visit, 24 May 2011. Discovery of Anglo-Saxon bed burial and cross.

673-730

Æthelthryth [St Aethelburg or St Etheldreda] founded a monastery at Ely in 673. She died at Ely in 679, leaving instruction that she be buried in a wooden coffin. Sixteen years after Æthelthryth’s death, brothers from the monastery travelled from Ely to Cambridge to obtain a stone coffin (a marble sarcophagus) from the ruins of the Roman town. In The Ecclesiastical History, c. 730, the Venerable Bede describes her way of life and refers to Cambridge as the little ruined walled Roman city of Grantacaestir .

Sources of information: Dr Sam Newton, Cambridge and the Kingdom of East Anglia, Institute of Continuing Education, University of Cambridge, November 2009. Campbell, J. (2008). Bede (673/4-735), Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press. [accessed 14 December 2010.] Thacker, Alan (2009). ‘Æthelthryth (d. 679)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press. [accessed 14 December 2010] The Victoria History of the Counties of England (1959). The History of the County of Cambridge & the Isle of Ely. Volume III. The City and University of Cambridge. City of Cambridge, page 2.

8th-9th century

Vikings from Norway and Denmark raided England from the late 700s. The Great Army of Danish Vikings landed in England in 865 and defeated most of the English kingdoms over the next few years, including East Anglia in 869-70. In 878, the West Saxon King Alfred [Ælfred] rallied his troops against the Vikings. By 886, he had captured the London area and made peace with the Danish King Guthrum but the Danes retained control of the north and east of England (the Danelaw).

In East Anglia, a Danish army led by King Guthrum established Eastern Danelaw, in 880-81 according to the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle. The Cambridgeshire area was a conflict zone between Mercia and East Anglia. The Danes reorganised the southern part of the county, including establishing a fortified enclosure and mint in Shelford. Cambridge developed as a defensive and commercial centre, called Grante-brycge in the Chronicle. The Danes in this area were defeated by Edward the Elder in 917, but were not forced to give up their land, so there was continuity.

There was a probable change in land use from dispersed farmsteads to the communal cultivation of large open fields divided into strips, requiring greater co-operation between the owners of the strips. The previous settlement pattern had been scattered hamlets and farmsteads and this farming change may have lead to the development of villages.

Sources of information: Dr Sam Newton, Cambridge and the Kingdom of East Anglia, Institute of Continuing Education, University of Cambridge, November 2009. Medieval London gallery, Museum of London. Costambeys, Marios (2008). ‘Guthrum (d. 890)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press [accessed 14 December 2010]. Kirby, Tony and Oosthuizen, Susan (eds.) (2000). An Atlas of Cambridgeshire and Huntingdonshire History. Cambridge: Anglia Polytechnic University. Map 26, 30. Oosthuizen, Susan (1996). Cambridgeshire from the Air. Stroud: Alan Sutton Publishing. Page 25. The Victoria History of the Counties of England (1959). The History of the County of Cambridge & the Isle of Ely. Volume III. The City and University of Cambridge. City of Cambridge, page 2- 3. Wormald, Patrick (2006). ‘Alfred (848/9-899)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press. [accessed 14 December 2010].

c. 890-905

King Alfred (c. 849 – c. 899) ordered the writing of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle. Written in Old English, copies were distributed across the country and updated locally. Nine copies survive, including one in the Parker Library, Corpus Christi College, Cambridge.

Sources of information: Evolving English: One Language, Many Voices, exhibition at the British Library, 2010-11. Anglo-Saxon Chronicle (Wikipedia) [accessed 14 December 2010]. Wormald, Patrick (2006). ‘Alfred (848/9-899)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press. [accessed 14 December 2010].

10th century

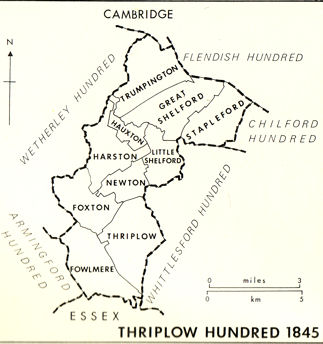

The County and Hundred boundaries within Cambridgeshire became established in the early 10th century.

The nucleated village of ‘Trumpington’ and the use of that name also become established in the 10th century. Trumpington appears to be one of a number of parishes to the south of Cambridge with names formed from a personal name and ‘ton’.

Most place names in Cambridgeshire are Anglo-Saxon in origin. Names ending in ‘ton’ tend to have formed later than those ending in ‘ham’. The ‘ton’ suffix is more common in the Mercia area west of the Cam.

Sources of information: Kirby, Tony and Oosthuizen, Susan (eds.) (2000). An Atlas of Cambridgeshire and Huntingdonshire History. Cambridge: Anglia Polytechnic University. Maps 26, 31.

10th century

By the late Anglo-Saxon period, Cambridge was established as the county town and an important market for the area. It was developing to the south east of the Roman river crossing. There was a ditch, the ‘King’s Ditch’, around the new settlement, probably intended as a customs barrier rather than a defensive line. The Ditch was crossed by two routes out of Cambridge to the south and east, the road to Trumpington and the highway on the line of the Roman road towards Colchester. The route now called Trumpington Street was the primary focus for the development of the town, reaching as far as the King’s Ditch. A series of churches were established along this route, including St Botolph’s on the town side of the King’s Ditch, dedicated to the patron saint of travellers. By the 13th century, there were tollgates on the two routes, ‘Trumpington Gate’ and ‘Barnwell Gate’. The King’s Ditch limited the development of Cambridge to the south and east until the open fields were enclosed in the 19th century.

Sources of information: National Monuments Record web site [accessed 22 December 2010]. St Botolph’s Church Web site [accessed 23 December 2010]. Taylor, Alison (1999). Cambridge: the Hidden History. Pages 45-49 and map page 46. The Victoria History of the Counties of England (1959). The History of the County of Cambridge & the Isle of Ely. Volume III. The City and University of Cambridge. Medieval Cambridge, page 3 and Economic History, page 89.

991

Ealdorman Beorhtnoth [Brihtnoth or Byrhtnoth] died a hero during the Battle of Maldon (Essex), leading the Anglo-Saxon fight against the Vikings. He owned extensive land in Cambridgeshire and other counties. In his will, he left the monks of Ely nine estates, including a manor at Trumpington. The bequest was completed on the death of his wife, Aelfflaed, who died c. 1006. Ely was accumulating a great deal of property, particularly by purchase between 970 and 1020, following the refoundation of the monastery.

Sources of information: Abels, Richard (2004). ‘Byrhtnoth (d. 991)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press. [accessed 14 December 2010.] Liber Eliensis. A History of the Isle of Ely from the Seventh Century to the Twelfth, Compiled by a Monk of Ely the Twelfth Century. Translated by Janet Fairweather (2005). Woodbridge: Boydell Press. Pages 160-63. Miller, Edward (1951). The Abbey and Bishopric of Ely. Cambridge: CUP. Pages 16-23. Taylor, Alison (1999). Cambridge: the Hidden History . Pages 129. The Victoria History of the Counties of England (1982). A History of Cambridgeshire and the Isle of Ely, Volume VIII. Armingford and Thriplow Hundreds. Trumpington, page 251.