Brian Goodliffe

This is one of a series of pages about farms and farming in Trumpington, based on presentations at the meeting of the Group in October 2009. See the introduction to farms and farming for more information.

I have also contributed my memories of Trumpington in the 1940s and 1950s

Throughout history, the people who worked the land, as opposed to owning it, have always had one thing in common: poverty. Agricultural wages have always been among the lowest; and were certainly still so in the 1950s. For farm workers and their families, austerity wasn’t just a period after the Second World War; it was a permanent way of life – especially in the winter, when no overtime was available.

For a winter Sunday-tea, my mother would often finely chop a home-grown onion or two and share it out onto tea plates. It would be sprinkled with sugar and malt-vinegar and eaten with bread and margarine. I always thoroughly enjoyed it, even though eating it with tears in my eyes, but from the onion, rather than any sense of deprivation. I assumed everyone ate such things for Sunday tea.

One Sunday tea-time someone knocked on our front door. Whilst my father went to answer it, my mother hastily gathered up all our half-eaten plates of onion and hid them round the corner on the stairs. And even though I was only around ten or eleven years old, I immediately picked up on her sense of shame.

In 1955, much to my parents’ delight, I passed my 11-plus exam and was offered a place at what was then Cambridge Central School for Boys, on Parkside, adjacent to Parkers Piece. But they weren’t quite so delighted when they received the list of all the uniform, sports gear and other equipment with which I had to be kitted out. I got to wear my smart new uniform rather a lot during the summer holidays of 1955, as my proud mother paraded me like some kind of prize-bull in front of friends and family and indeed anyone else she could find to impress.

Given the price differential, I became among the very last of my peer group still in short trousers. Strange as it may sound, in the end it was our GP who eventually “prescribed” long trousers for me. His surgery was just across the road from the top of Maris Lane. For several winters I’d suffered from painful and itching chilblains on my toes. I had tried the “old wives” remedies of rubbing with raw onion (raw onion seems to have been very prevalent in my childhood!), and had even – with grimacing face and teeth firmly clenched – tried the “chamber-pot treatment”. That’s how desperate I was. But to no avail. In the end I took myself to the doctor. Upon seeing my exposed stick-thin frozen legs, in delicate shades of purple and orange, he quickly diagnosed that the problem was a serious deficiency in long trousers and wrote a note, confirming same, to give to my mother. I could have kissed him! The long trousers not only raised my poor self-esteem a couple of notches: they did indeed cure my chilblains.

But let’s go back to the beginning of my years in Trumpington. In November 1946, my late father, Ron Goodliffe, got a job as a tractor driver on the Pemberton estate and we moved into a tied-cottage in Swan’s Yard, a small row of terraced cottages that used to be off the east side of the High Street, vaguely opposite what I believe was called The Red House, where the nurse lived. I was two-and-a-half.

In 1948, we moved to 18 Grantchester Road, or Dated Cottage, as it was then known, as it had the year 1654 emblazoned on the front in big metal numbers. On the photo taken a few years later, I’m standing back left, with my brother in front of me, and with two of the Parr brothers beside us. They lived in the other half of the cottage: number 16. It’s their front door you can see. Our front door was actually on the left hand side of the property.

Then, in 1954, we moved next-door-but-one into 22 Grantchester Road, otherwise known as Park Cottage, opposite the church. Bearing in mind the thatched roof, I remember that Guy Fawkes Night was always a very stressful time for my dad. Any rockets or other fireworks that shot things out would be aimed at 45 degrees, over our eight-foot garden wall into Trumpington Park, where they could do far less damage. My brother Mick and I would see the whoosh as they set off, but from our lower eye levels we missed most of the coloured starbursts that the adults were ooing and aahing over. But at least we kept a roof over our heads.

I was very much a Free-Range child. With my father working for the Pemberton’s, I bestowed upon myself the free run of their vast estate. If I happened to know where my Dad was working, I might set off on my bike to find him and hopefully get a ride on a tractor, and, as I got older and could reach the pedals, occasionally get to drive it.

The general-purpose tractors on the Pemberton farms at that time were mainly a mixture of Fordson Majors, the ubiquitous Fergusons (usually referred to as Fergies) and an Allis-Chalmers Model B. That’s my Dad driving the latter and my head you can just see peering out behind him. The other two chaps were two of the three Irish labourers who were hired to build the concrete access road, for what I believe was the County Agricultural Show that year, held on the land roughly opposite Gazeley Road. After the show they stayed on to help with the harvest.

Digressing slightly: I came home from school one day, and in the distance I could see a barrage balloon high in the sky. Following the line of sight I walked across Trumpington Park and a couple of fields until I reached where it was being winched down by a large army-type truck. It was on the very same fields as the Show had been. Immediately under the balloon was a sort of open-fronted cabin. Once the cabin was at ground level, a dozen or so soldiers climbed aboard, and up it went again. With the balloon several hundred feet up, the winch stopped and all went quiet again. Then suddenly the soldiers up in the cabin started leaping out and gently parachuting down to earth. An exciting spectacle indeed for a young lad like me.

Once the cereals had been combined and the bales of straw carted away, the next job was to dispose of the remaining stubble. In those days it was burnt off; and great columns of smoke could be seen all over the countryside, as hundreds of acres of stubble were torched. Can you imagine the fun I had? Helping my dad deliberately set fire to a field, and making sure that the fire was spreading – by scattering burning straw from the end of a pitch-fork. It would have been worthy of a Jim’ll Fix-It request!

Once the stubble was burnt off my dad would be driving his favourite steed, an Allis-Chalmers model M, known as a crawler or caterpillar because of its tracks. Pulling in turns a plough, discs and then rollers, the soil would be worked into a fine tilth, ready for sowing next year’s crop.

Farming equipment has always been potentially hazardous and there were occasions when my father must have put great store in my sense of self-preservation. One that now makes me cringe with utter disbelief is the procedure of seed drilling. The best illustration I can find for my purpose happens to show a horse-drawn model, but they had not actually changed much by the 1950s. In fact most would have been converted from horse- to tractor-drawn in farm workshops up and down the country.

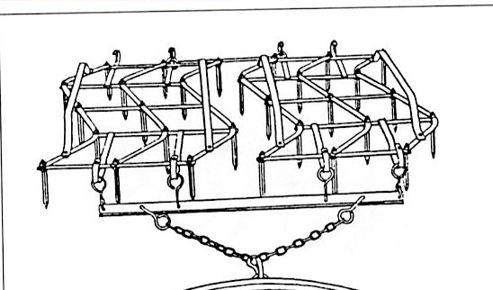

On the back of this implement was a narrow foot-board upon which I used to ride; while my dad drove the tractor, very much concentrating on keeping a straight line ahead. At this point it doesn’t sound too dangerous. After all, I wasnt that far off the ground, and we were probably doing no more than a decent jogging pace. But take away the horses; and replace them with a tractor, so noisy that two people sitting on it side-by-side couldn’t hold a normal conversation. And in order to carry out in one operation, what the horses would have had to do in two, there were, being towed only a few feet behind it, a set of harrows. In fact there’d be three pairs like the ones in the picture, side by side, the full width of the drill. And each individual section of harrow had 15 spikes that were drawn through the soil to ensure the seeds were properly covered. If I’d slipped off that foot-board I’d have been dragged under those harrows in a trice and by the time they’d spat me out I’d have resembled an Aberdeen Angus meatball. Maybe that’s the origin of the term “a harrowing experience”!

Occasionally I’d do the rounds with the Gamekeeper, Mr Stimpson, and started taking dead trapped moles home to skin with the idea of making a moleskin-waistcoat like the one I’d read about in the series of “Romany” books that I’d pick up after school from Cambridge Central Public Library, which in those days was situated in Corn Exchange Street. Having removed the skins, I pinned them out onto a board to dry, as the first stage of the curing process, but then my mother said there was no way she was going to handle them to do the necessary needlework, so that project was doomed at a very early stage.

I’ve already mentioned the very low wages. There was at the time a fledgling Union of Agricultural Workers and, very uncharacteristically, my father was some sort of local Secretary for same, but when you’re living in a house that goes with your job you’re not exactly inclined to be too militant.

However, I don’t want you to think that the Pemberton’s were some kind of feudal ogres. They were merely paying the going rate. But they did help in other ways. They had hot water systems installed into both our Grantchester Road cottages. We take running hot water in our kitchens and bathrooms for granted these days, but back then many people still just had the one cold tap over the sink and as for a bathroom, well, most people were grateful for an indoor toilet!

I can actually remember them installing the Rayburn Back-Boiler in Park Cottage and when all the fire-clay had dried one of the estate workers (Les Dear? Charlie Hunt? I’m afraid most of the names have long since got muddled or faded from my memory) showed me how to start a proper fire with scrunched up newspaper and sticks under the coal. And Joe Kefford, the farm carpenter, made us a new wooden draining board. I remember being absolutely spellbound as he neatly gouged out the drainage grooves with some sort of complicated hand-plane. The Pemberton’s also paid for decorating materials, so my parents could redecorate inside the cottages. Always done after I’d gone to bed. They weren’t silly!

And we used to get free fire-wood. In the winter months, each Saturday afternoon, two farm workers would take a tractor and two-wheeled trailer through a gate at the back of Trumpington Park onto the track that led to the poultry farm. On the right hand side of this track was an area where all the fallen trees and large branches from the estate were dumped. Using a tractor-powered saw-bench they’d fill the trailer with logs before driving to their respective homes and off-loading half a trailer’s worth at each.

Also, whilst living at number 18, so sometime between 1948 and 1954, I have very vague memories of each farm-worker receiving half a pig. In common with most people then, we didn’t have a fridge, never mind a freezer, so I believe it was cut into manageable pieces and hung over the fire to dry cure. Apparently my paternal grandmother came over from Balsham on the bus in order to make my Dad some brawn from the half a pig’s head. My mother, being extremely squeamish, would have rather just wrapped it in newspaper and put it in the bin.

Like most ploughmen, my father was perfectly happy with his own company, but it wasn’t the most glamorous of jobs. We used to have proper winters back then, and tractors were still totally cab-less and open to the elements. He would plough on, literally, through everything the skies had to throw at him. Often soaked through and chilled to the bone, he would guide his beloved Allis-Chalmers, keeping the furrows as straight as a die – the hallmark of an expert ploughman.

One-hundred-and-thirty people turned up at the church for my father’s funeral service, in the small village of Willian, near Letchworth, where he’d lived for the last forty-five of his eighty-six years. Of these 130 people, just 15 could be classed as family. The rest were friends and acquaintances who just wanted to pay their last respects to a much liked and respected man. One couple, whom he used to do gardening work for in the village after his retirement, had since moved to Devon. Starting in the early hours, they drove up just for the service; then turned around and drove back to Devon again afterwards. All the pews were full; all the extra chairs put out were full; and there were people standing. My one regret, which I’ll have for the rest of my life, is that by the time we got back from the crematorium virtually all these people (the vast majority of them total strangers to me) had softly melted away as quietly as they had arrived. I should so liked to have shaken them each by the hand and asked them how they knew my Dad.

To get back now to the Trumpington connection, I would like to finish by offering an extract from a poem entitled Unspoken Love that I composed for my father’s funeral. But first, bear in mind that our family name is Goodliffe; and that probably less than half-a-dozen people in the church would know ‘who’ “Alice Chalmers” was. You should’ve seen the ears prick up as the first three lines were read out! My dad would have enjoyed that joke.

But there was another love in your life,

By the name of Allis-Chalmers.

And you spent many hours alone in her company

As she ploughed each field with furrows.

As a child I’d sometimes join you on her ample bench type seat.

The constant roar of the engine and the screaming of the gulls

Made conversation difficult

And I often fell asleep.

So you’d put your strong arm round me,

To stop me falling and getting crushed,

And we’d plough. . . ’till after sunset

Then bike home. . . through the dusk.

This is how we bonded,

. . . a father . . . and his son.

. . . In silence . . . on a tractor,

The three of us as one.

Many hours I spent in your company

Through all seasons on the farm.

The other workers called me Young Ron,

To which I proudly warmed.

You were such a gentle man,

Moderate of voice and slow of hand.

You gained respect through love, not fear,

And sowed seeds of common decency in the minds of both your sons.